Your enquiry email was sent successfully.

Your email was sent successfully.

Your favorites email was sent successfully.

Summer Exhibition 2024

Dear collectors, artists, art lovers, dear friends,

May 2024 brings a lot of colour, inspiration and joy to my little house in Riehen thanks to the support of old, loyal and unselfish friends. Works of the highest quality and best provenance, many of them little gems, just like my workplace. I feel a deep, warm sense of gratitude and am happy that I probably didn't do everything wrong in my previous working life when I unconditionally and transparently placed humanity, love and respect for the work of the creators and the people who care for this work at the forefront of my work.

More than half a year has now passed since the opening of my gallery in Riehen, opposite the Fondation Beyeler. Every single day has been exciting and characterised by meeting many new people from all over the world. Time flies by like a rush.

The location means that I have to deal with an unaccustomed number of visitors; there are days when I welcome more visitors here than I was able to do in three months at the previous gallery. Not a single negative experience, no derogatory or unfair comments, it's nothing short of a miracle.

If our crazy world could now also find some peace, if people could dare to give themselves something beautiful and inspiring again, if everyday life could be characterised by fewer fears, doubts and insecurities, I would also be completely relaxed about the future for all of us.

I will be opening the 2024 summer exhibition at the beginning of June, celebrating more of my ‘heroes’.

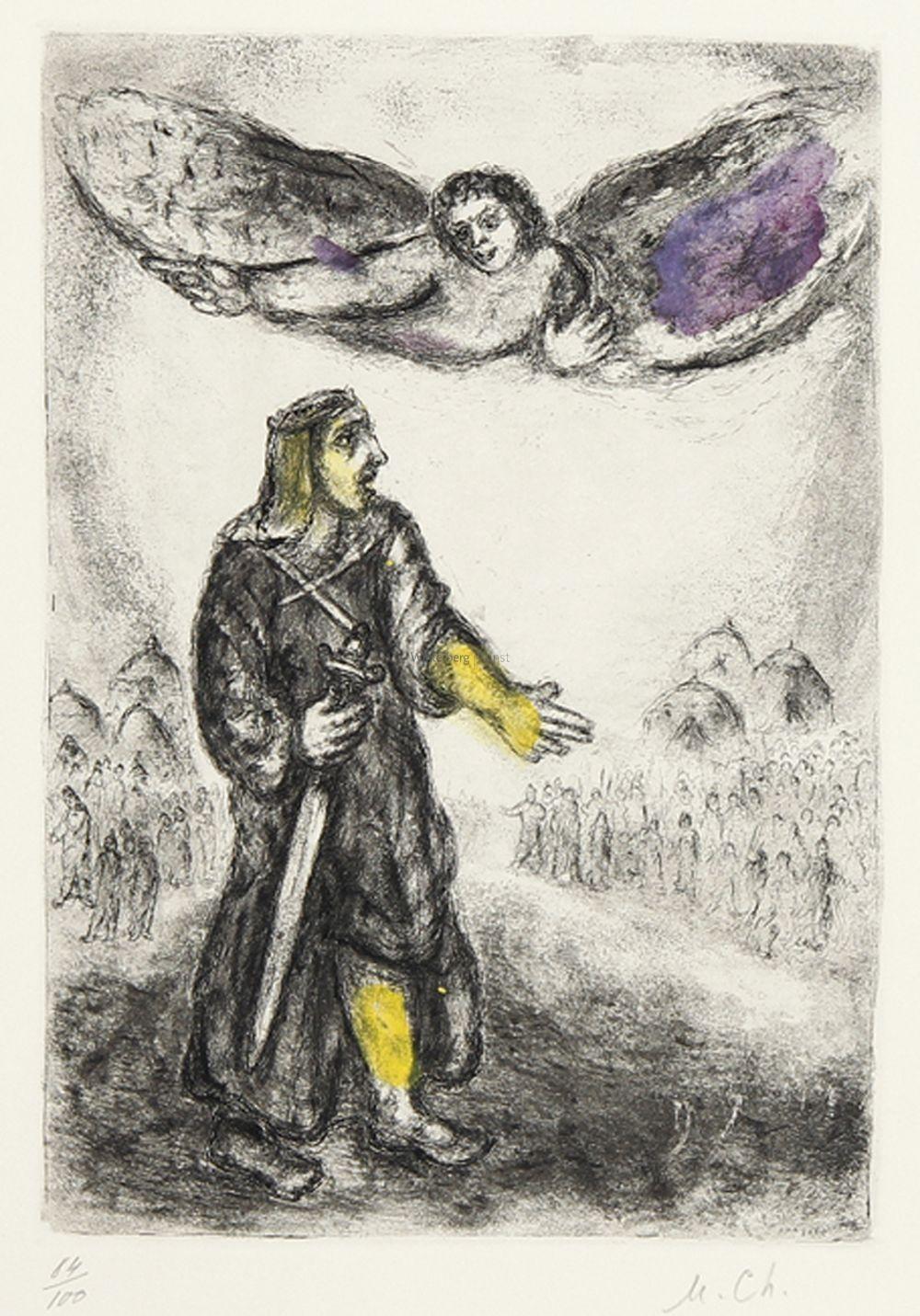

Witebsk 1887 - 1985 Vence

Josué devant Jéricho. Blatt 46 aus der Folge „La Bible“. In Gelb und Violett aquarellierte Radierung, 1931-1956/58.

Sorlier-Vollard 244. Aus Cramer Bücher 30. - Expl. 84/100. Monogrammiert sowie mit dem Namenszug in der Platte. Auf kräftigem chamoisfarbenem Vélin d’Arches. 33 x 22,6 cm (Blatt: 53,5 x 39 cm).

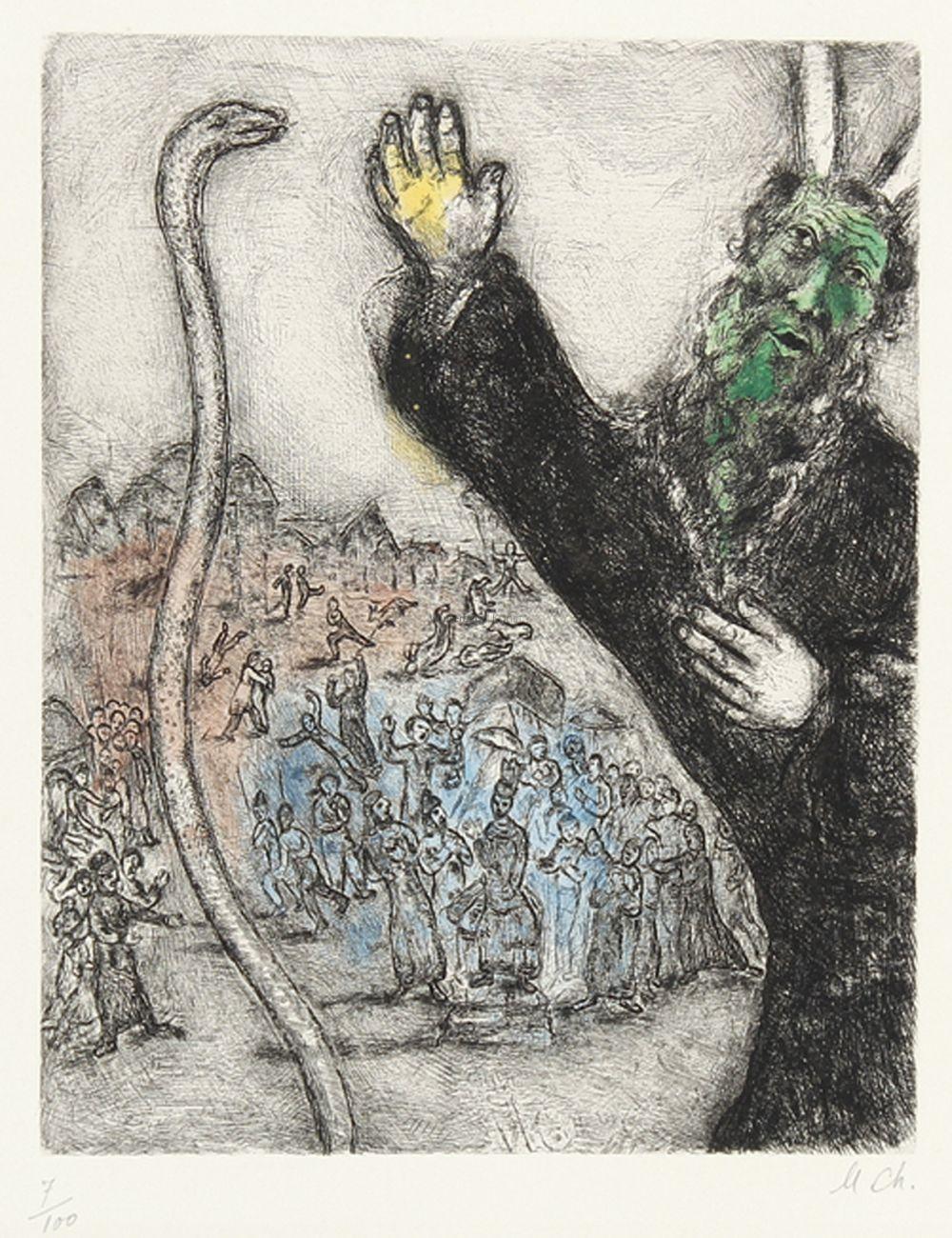

Witebsk 1887 - 1985 Vence

Moïse et le Serpent. Blatt 30 aus der Folge „La Bible“. In Grün, Gelb, Rosé und Blau aquarellierte Radierung, 1931-1956/58.

Sorlier-Vollard 226. Aus Cramer Bücher 30. - Expl. 7/100. Monogrammiert sowie mit dem Namenszug (unten rechts) in der Platte. Auf kräftigem chamoisfarbenem Vélin d’Arches. 29,5 x 23 cm (Blatt: 53,5 x 39 cm). Breite Ränder schwach gebräunt und Unterrand mit schwachen Farbspuren. Die bereits 1956 erschienene Folge von 105 in der Zeit von 1931-56 entstandenen Bibel-Radierungen wurde 1958 in einer 100er Auflage von Chagall aquarelliert.

The Staff of Moses, also known as the Staff of God is a staff mentioned in the Bible and Quran as a walking stick used by Moses. According to the Book of Exodus, the staff (Hebrew: מַטֶּה matteh, translated "rod" in the King James Bible) was used to produce water from a rock, was transformed into a snake and back, and was used at the parting of the Red Sea.[1] Whether the staff of Moses was the same as the staff used by his brother Aaron has been debated by rabbinical scholars.

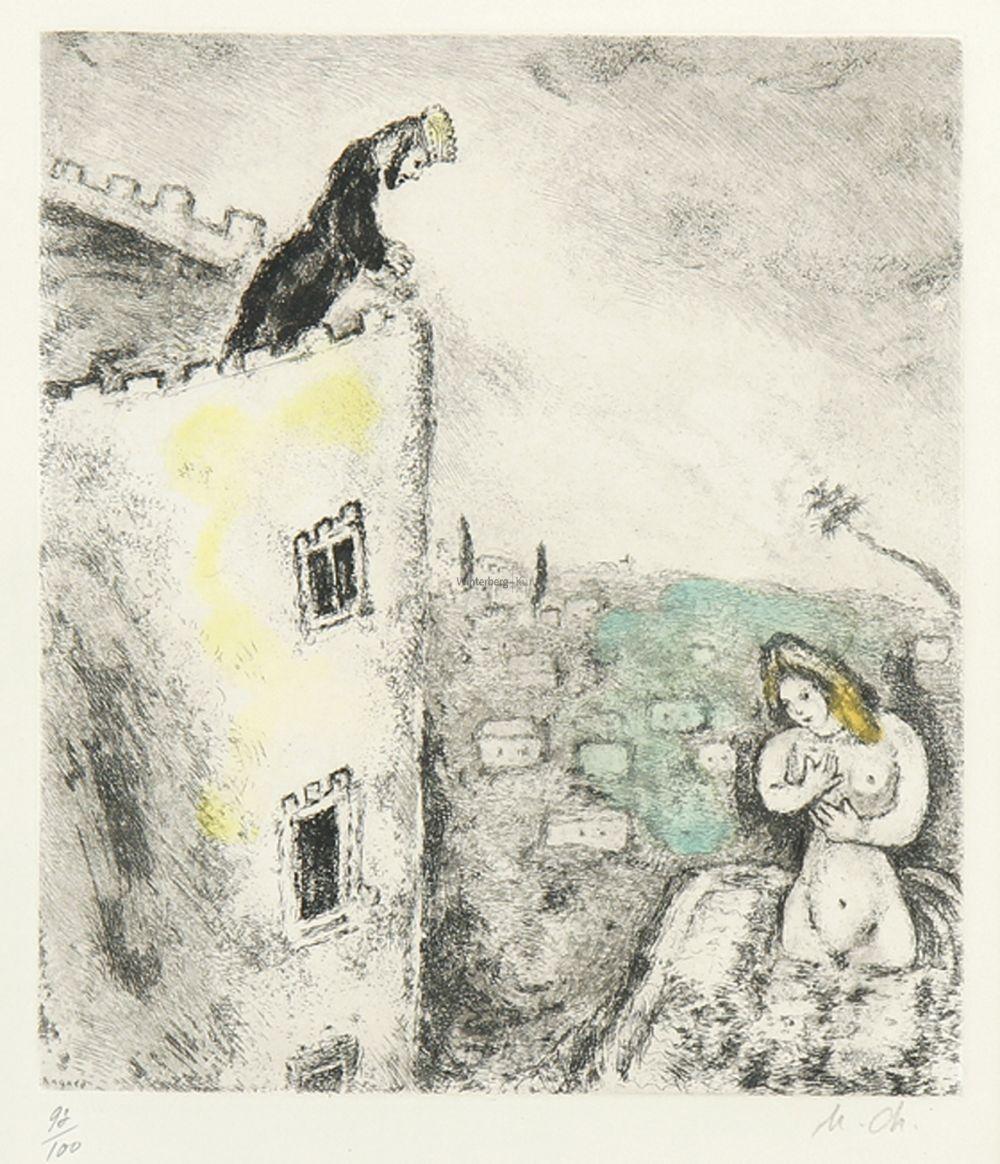

Witebsk 1887 - 1985 Vence

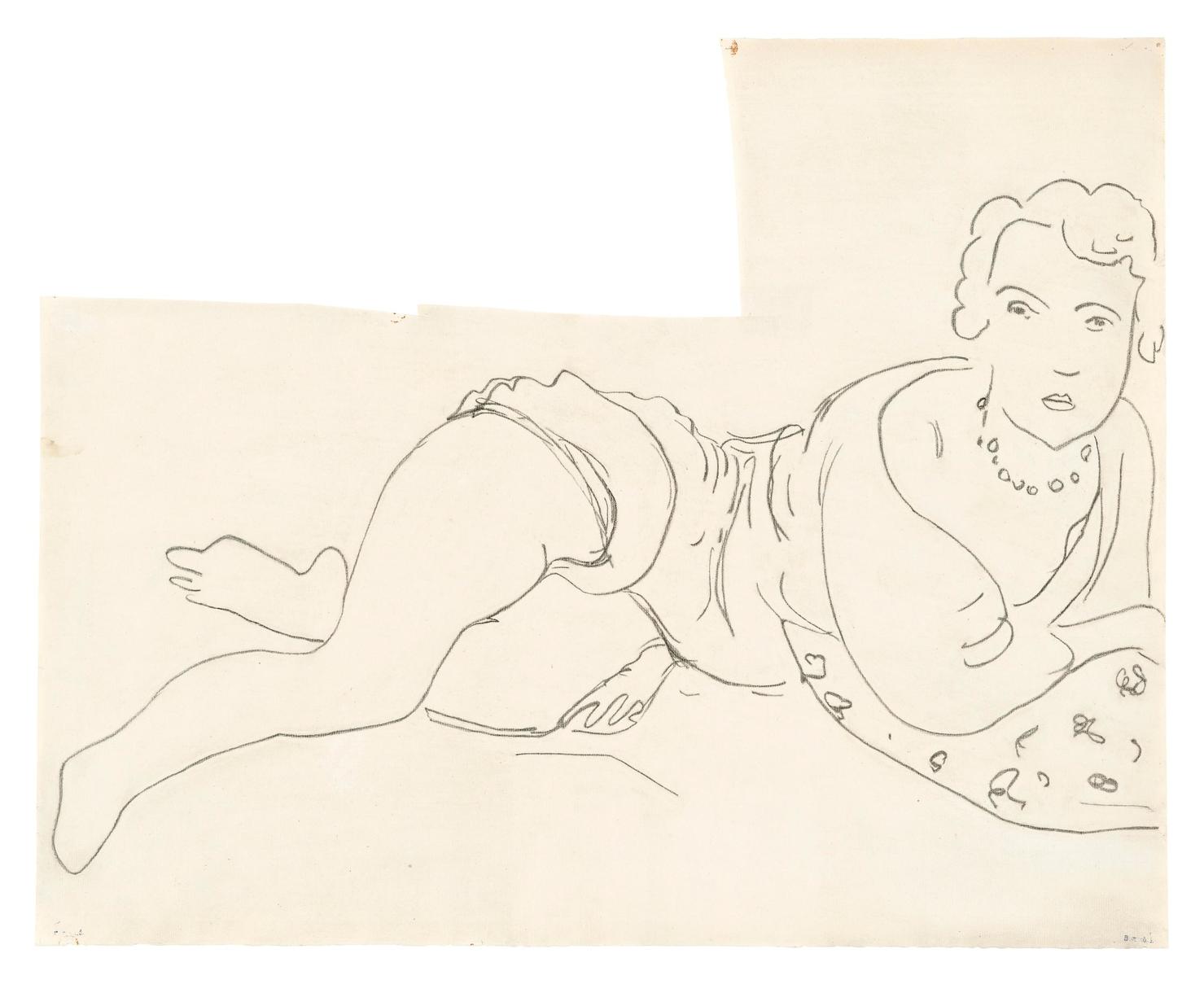

David et Bath-Schéba. Blatt 69 aus der Folge „La Bible“. In Gelb und Grün aquarellierte Radierung, 1931-1956/58.

Sorlier-Vollard 267. Aus Cramer Bücher 30. - Expl. 93/100. Monogrammiert sowie mit dem Namenszug in der Platte. Auf kräftigem chamoisfarbenem Vélin d’Arches. 28,5 x 25,2 cm (Blatt: 53,5 x 38,2 cm).

In the spring, at the time when kings go off to war, David sent Joab out with the king’s men and the whole Israelite army. They destroyed the Ammonites and besieged Rabbah. But David remained in Jerusalem.

2 One evening David got up from his bed and walked around on the roof of the palace. From the roof he saw a woman bathing. The woman was very beautiful, 3 and David sent someone to find out about her. The man said, “She is Bathsheba, the daughter of Eliam and the wife of Uriah the Hittite.” 4 Then David sent messengers to get her. She came to him, and he slept with her. (Now she was purifying herself from her monthly uncleanness.) Then she went back home. 5 The woman conceived and sent word to David, saying, “I am pregnant.”

6 So David sent this word to Joab: “Send me Uriah the Hittite.” And Joab sent him to David. 7 When Uriah came to him, David asked him how Joab was, how the soldiers were and how the war was going. 8 Then David said to Uriah, “Go down to your house and wash your feet.” So Uriah left the palace, and a gift from the king was sent after him. 9 But Uriah slept at the entrance to the palace with all his master’s servants and did not go down to his house.

10 David was told, “Uriah did not go home.” So he asked Uriah, “Haven’t you just come from a military campaign? Why didn’t you go home?”

11 Uriah said to David, “The ark and Israel and Judah are staying in tents,[a] and my commander Joab and my lord’s men are camped in the open country. How could I go to my house to eat and drink and make love to my wife? As surely as you live, I will not do such a thing!”

12 Then David said to him, “Stay here one more day, and tomorrow I will send you back.” So Uriah remained in Jerusalem that day and the next. 13 At David’s invitation, he ate and drank with him, and David made him drunk. But in the evening Uriah went out to sleep on his mat among his master’s servants; he did not go home.

14 In the morning David wrote a letter to Joab and sent it with Uriah. 15 In it he wrote, “Put Uriah out in front where the fighting is fiercest. Then withdraw from him so he will be struck down and die.”

16 So while Joab had the city under siege, he put Uriah at a place where he knew the strongest defenders were. 17 When the men of the city came out and fought against Joab, some of the men in David’s army fell; moreover, Uriah the Hittite died.

18 Joab sent David a full account of the battle. 19 He instructed the messenger: “When you have finished giving the king this account of the battle, 20 the king’s anger may flare up, and he may ask you, ‘Why did you get so close to the city to fight? Didn’t you know they would shoot arrows from the wall? 21 Who killed Abimelek son of Jerub-Besheth[b]? Didn’t a woman drop an upper millstone on him from the wall, so that he died in Thebez? Why did you get so close to the wall?’ If he asks you this, then say to him, ‘Moreover, your servant Uriah the Hittite is dead.’”

22 The messenger set out, and when he arrived he told David everything Joab had sent him to say. 23 The messenger said to David, “The men overpowered us and came out against us in the open, but we drove them back to the entrance of the city gate. 24 Then the archers shot arrows at your servants from the wall, and some of the king’s men died. Moreover, your servant Uriah the Hittite is dead.”

25 David told the messenger, “Say this to Joab: ‘Don’t let this upset you; the sword devours one as well as another. Press the attack against the city and destroy it.’ Say this to encourage Joab.”

26 When Uriah’s wife heard that her husband was dead, she mourned for him. 27 After the time of mourning was over, David had her brought to his house, and she became his wife and bore him a son. But the thing David had done displeased the Lord.

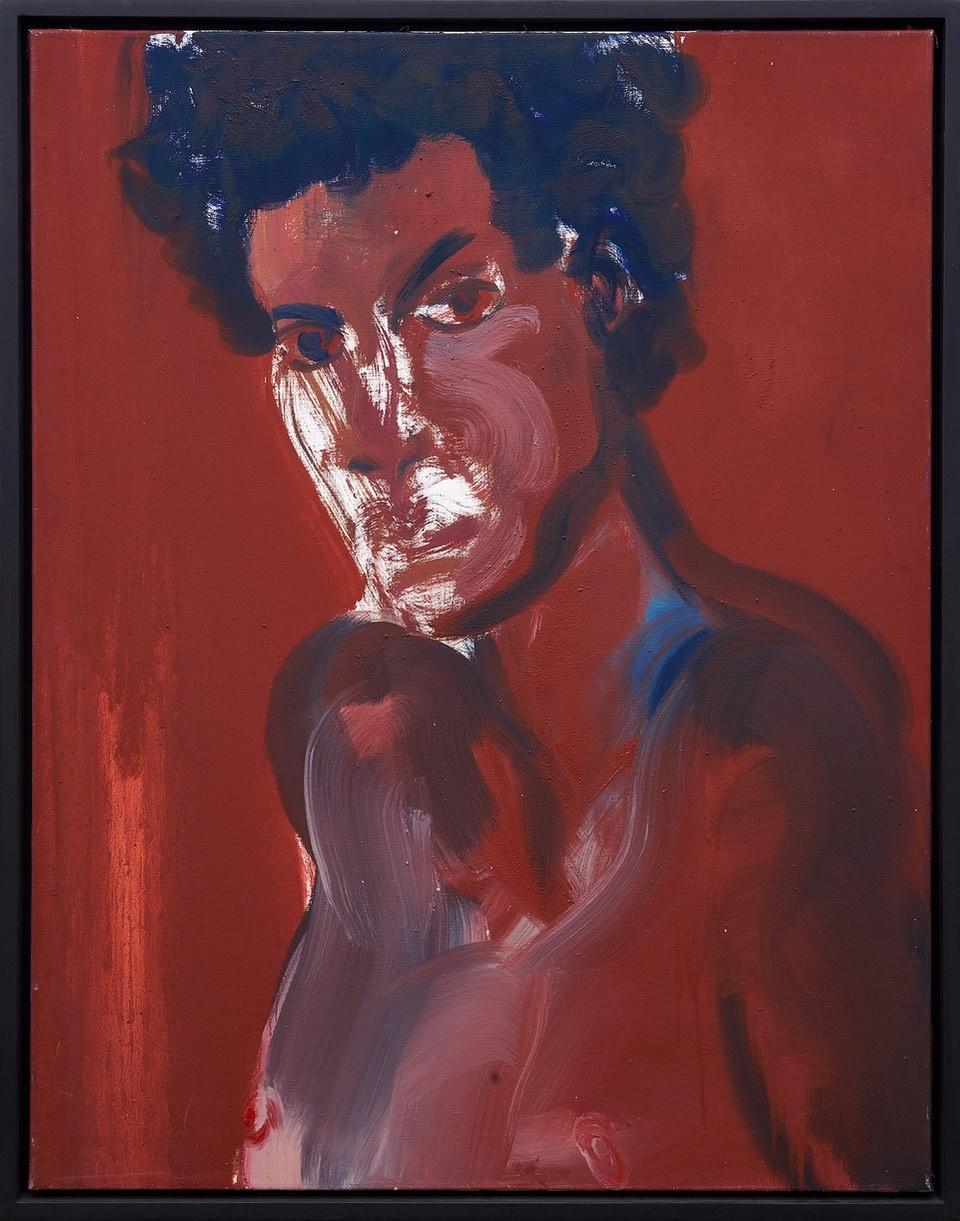

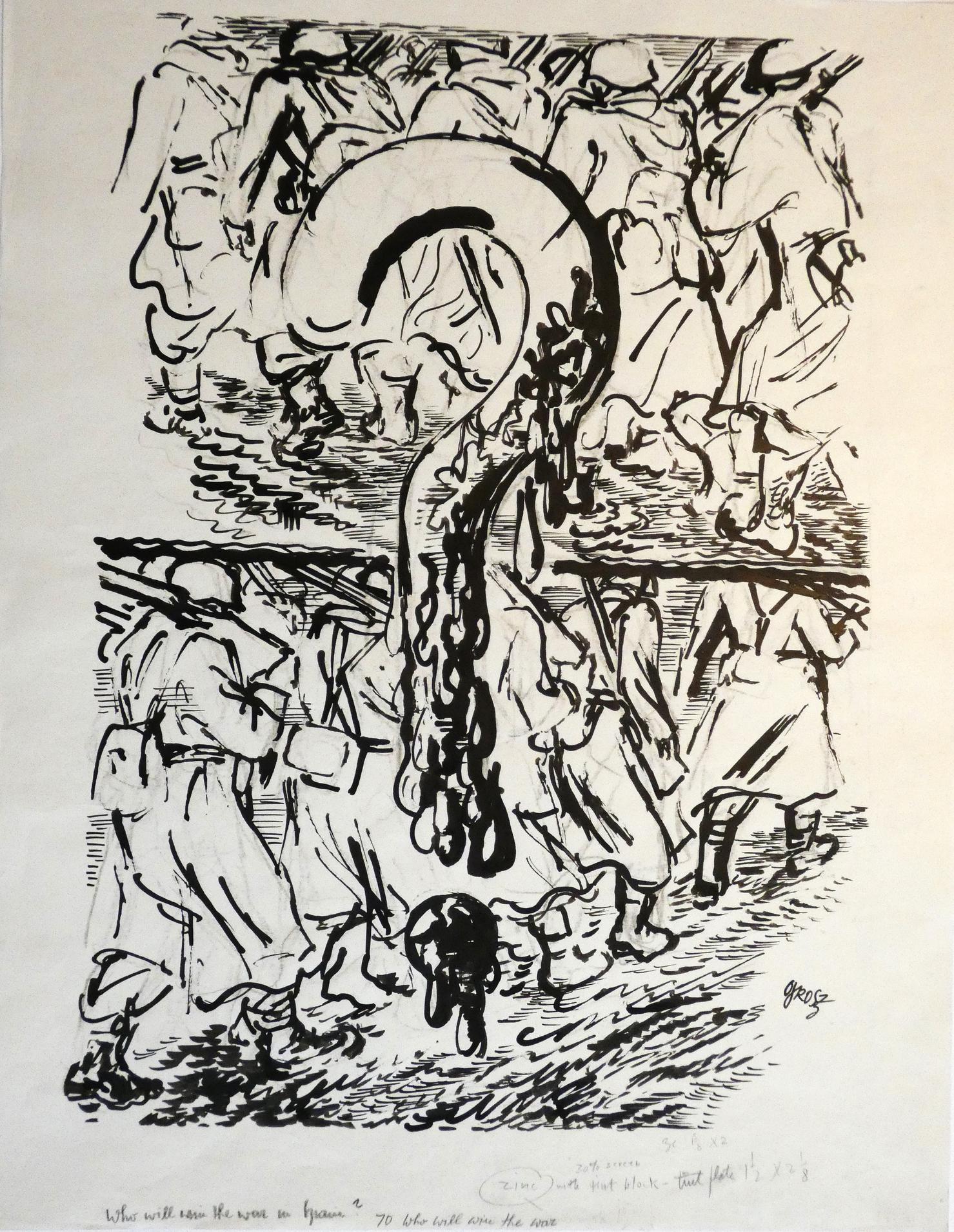

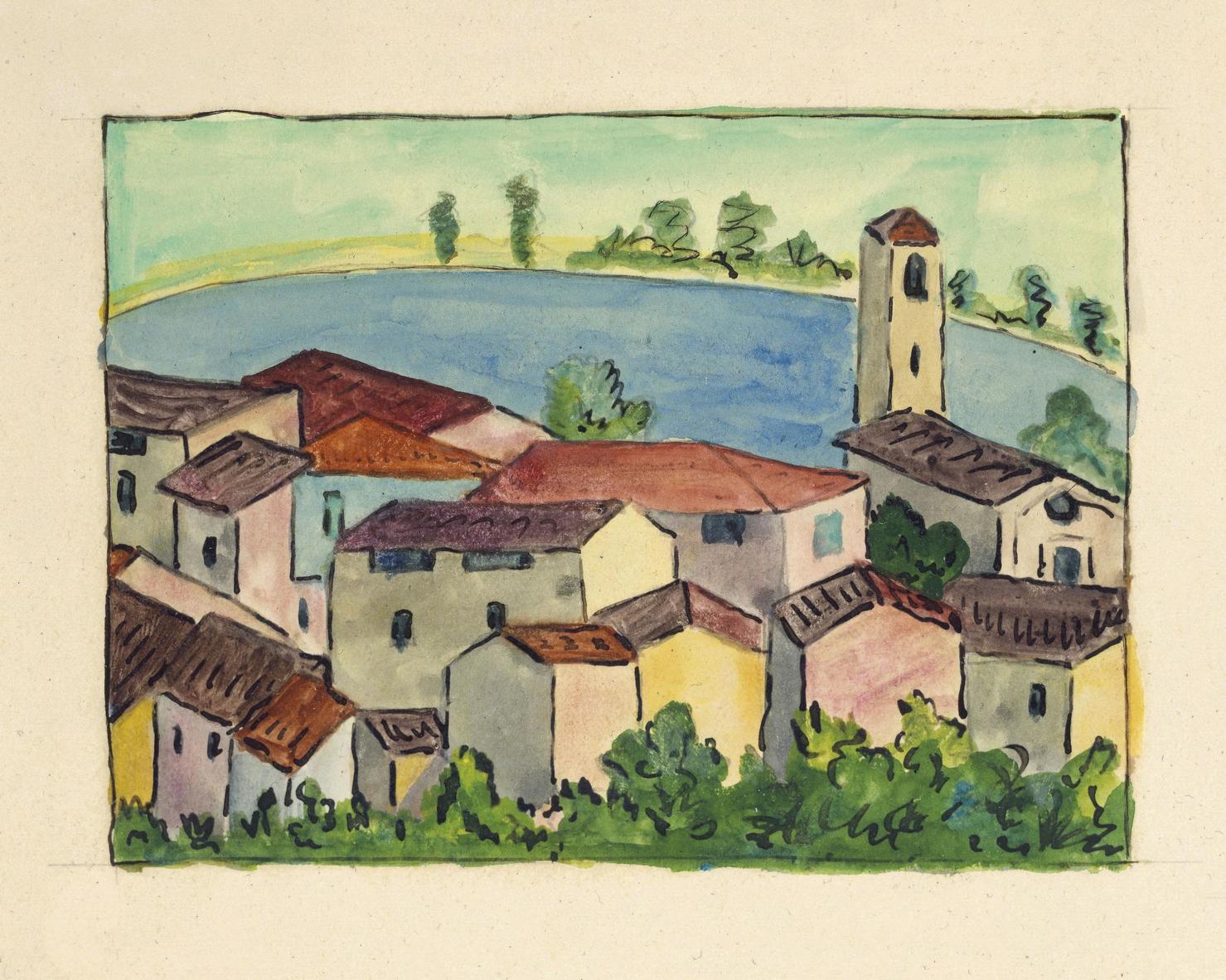

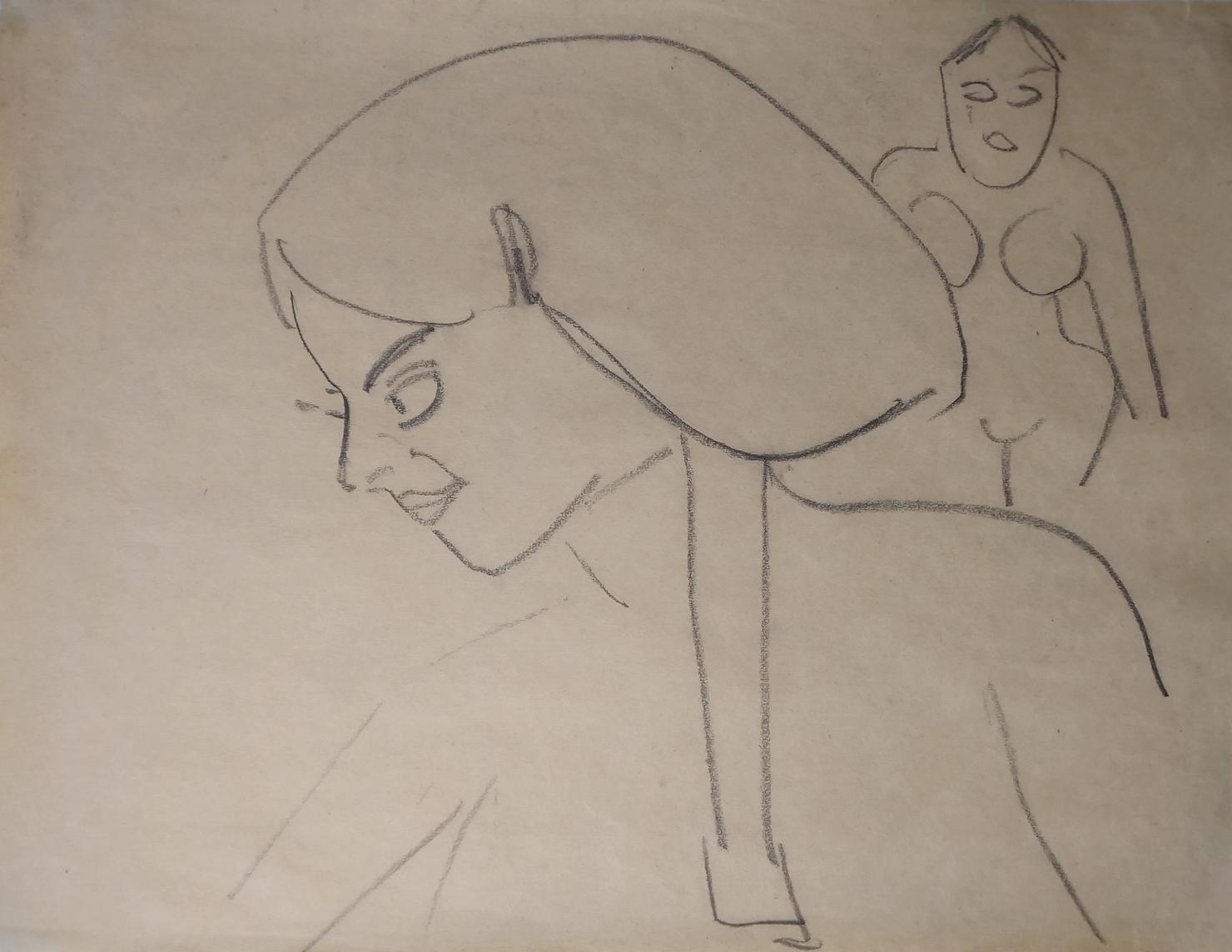

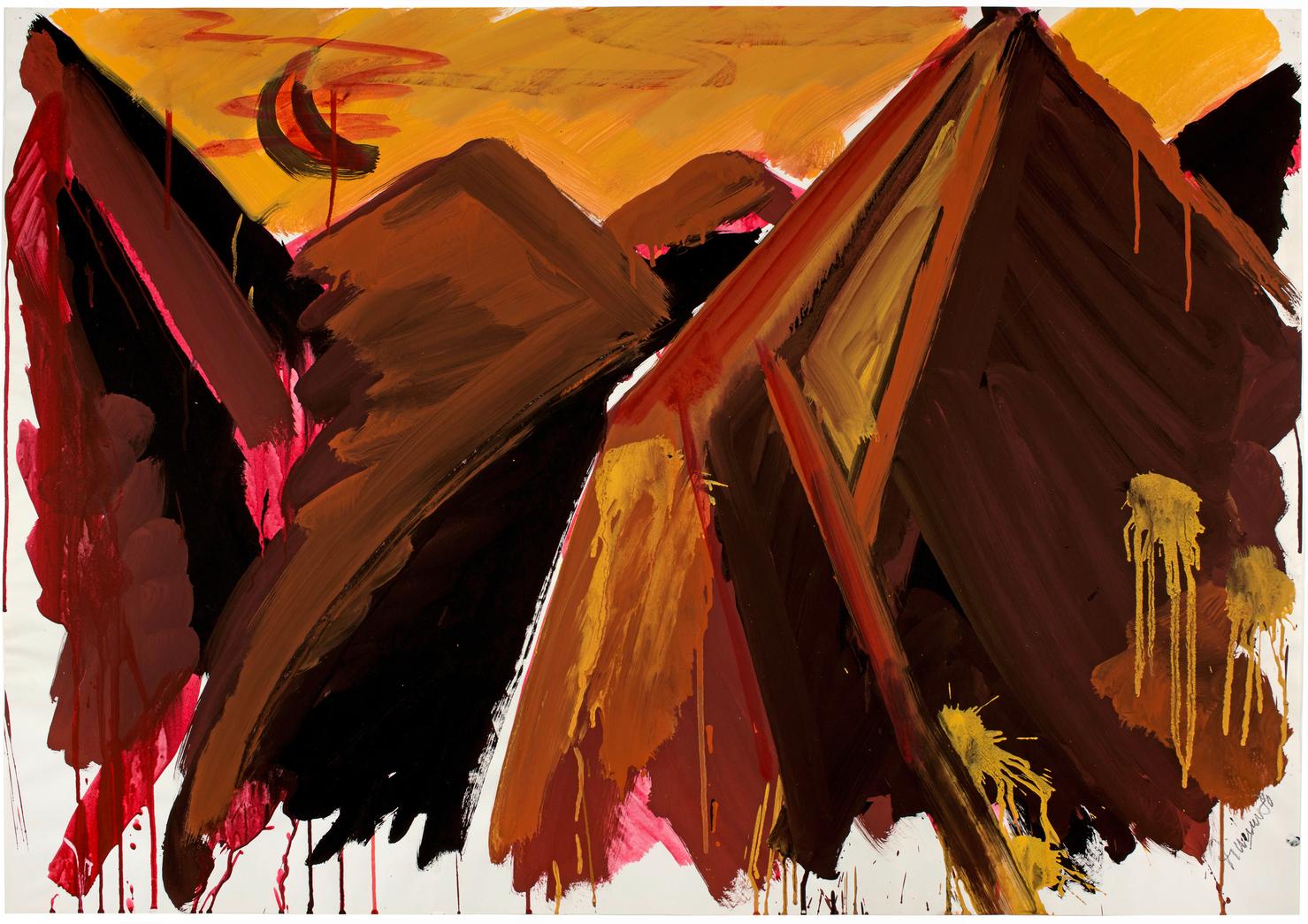

Acryl und Kohle auf Papier, durch den Künstler auf Leinwand aufgezogen. 140 × 107 cm (55 ⅛ × 42 ⅛ in.). Rückseitig mit einem Etikett der Galerie Studio d'Arte Cannaviello, Mailand.

[3009]

Provenienz: 2020 in der Galerie Studio d'Arte Cannaviello, Mailand, erworben

Zustandsbericht: In gutem Zustand. Die Farben frisch und intensiv. Die Ecken und Ränder des Papiers stellenweise minimal bestoßen und mit feinen Bereibungsspuren. Die Ecken mit Montierungslöchern. Vereinzelt winzige Fleckchen und das Papier punktuell minimal angeraut (Atelierspuren). Unter UV-Licht sind keine Retuschen oder Restaurierungen erkennbar. Schöner harmonischer Gesamteindruck.

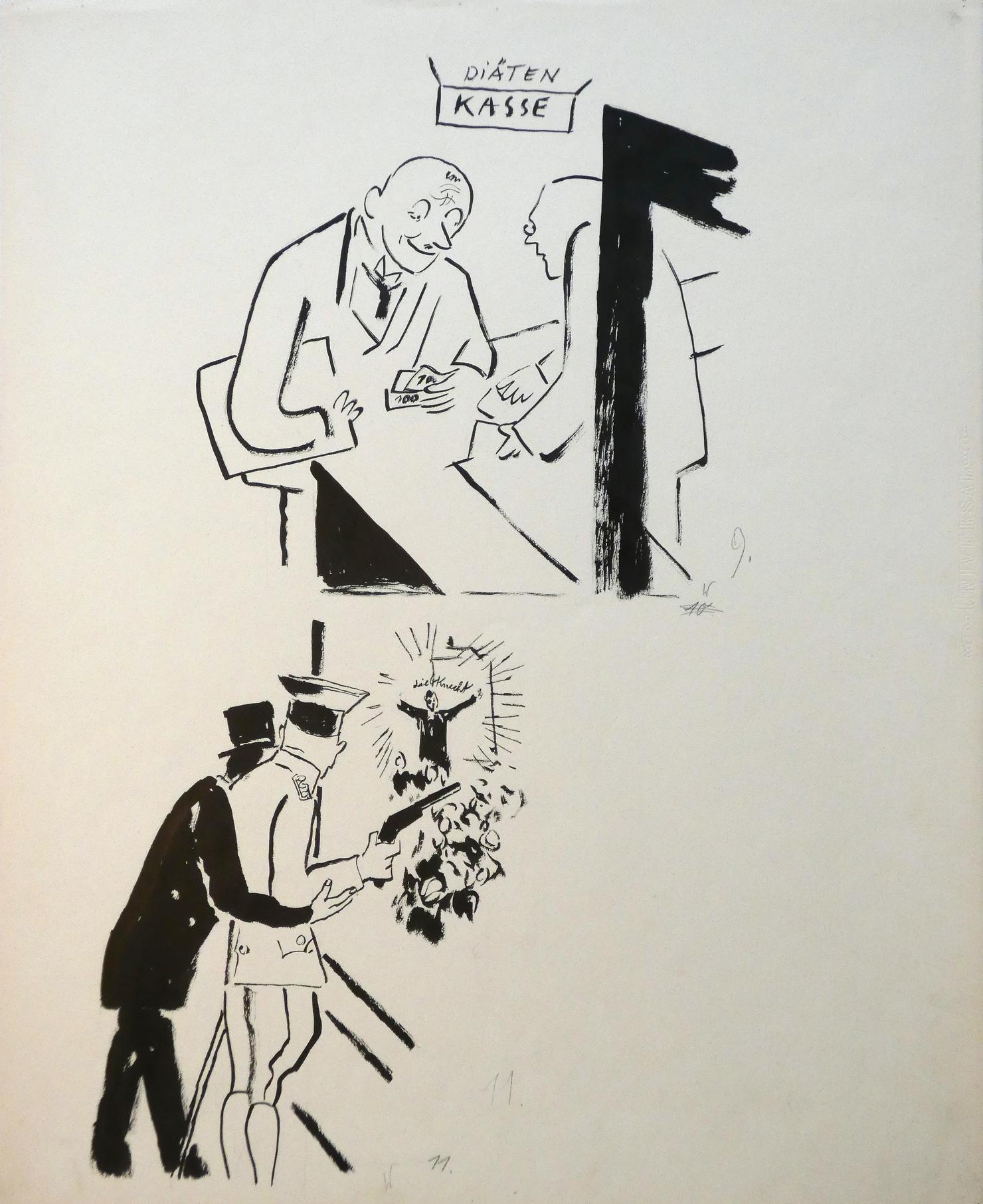

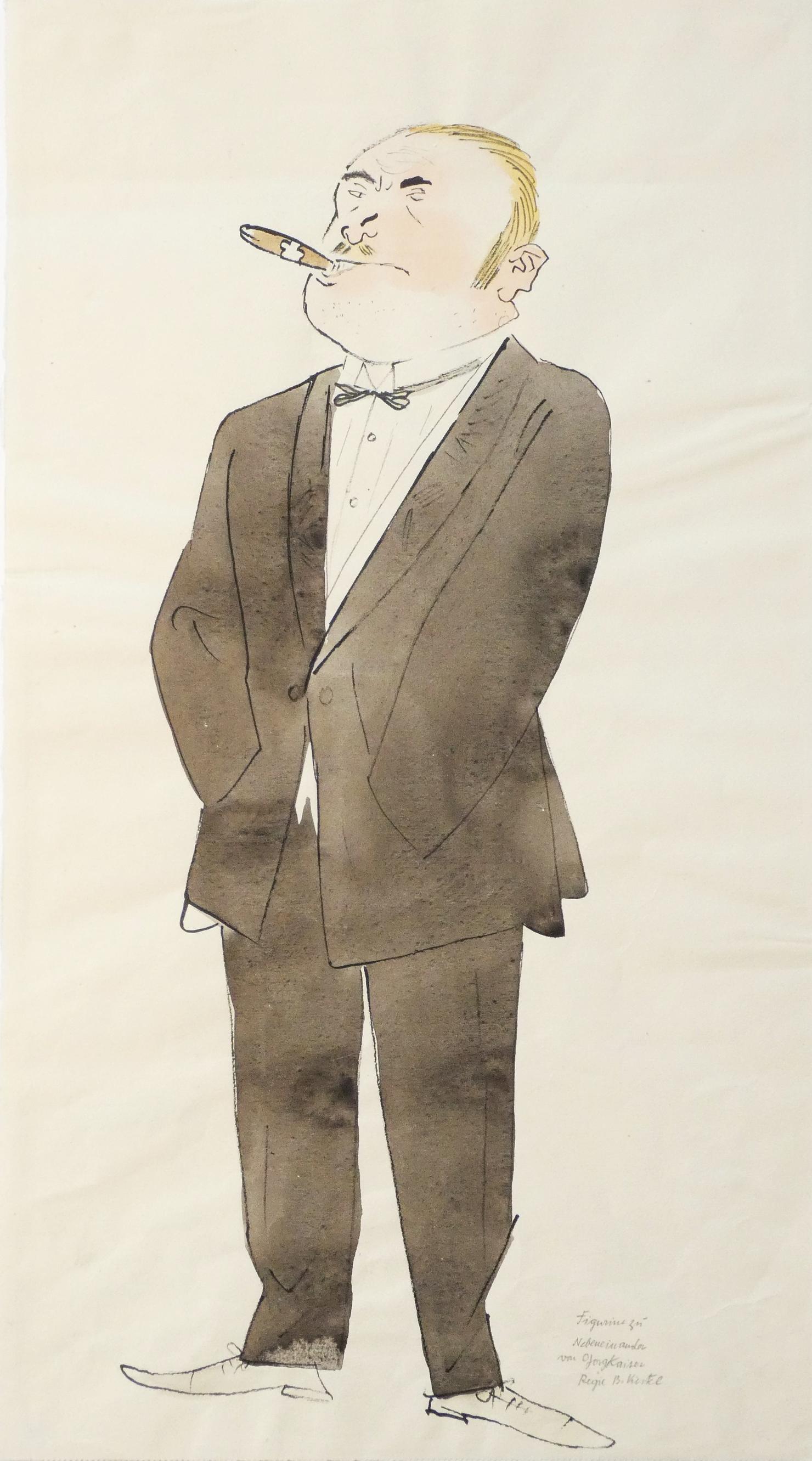

2007, Rom, ,,George Grosz. Berlin-New York'', Academie de France à Rome, Villa Medici, 9. Mai-

15. Juli, 2007, Kat.-Nr. 144, Seite 122

2015 Solingen, ,,George Grosz. Alltag und Bühne - Berlin 1914-1931'', 3. Mai-14. Juni, Abb. Seite 85.

Weitere Station 2015: Kunstmuseurn Bayreuth, 28. Juni-11. Oktober 2015

2015 Solingen, ,,George Grosz. Alltag und Bühne -Berlin 1914-1931'', 3. Mai-14. Juni,

Abb. Seite 107.

Weitere Station: Kunstmuseum Bayreuth, 28. Juni-11. Oktober 2015

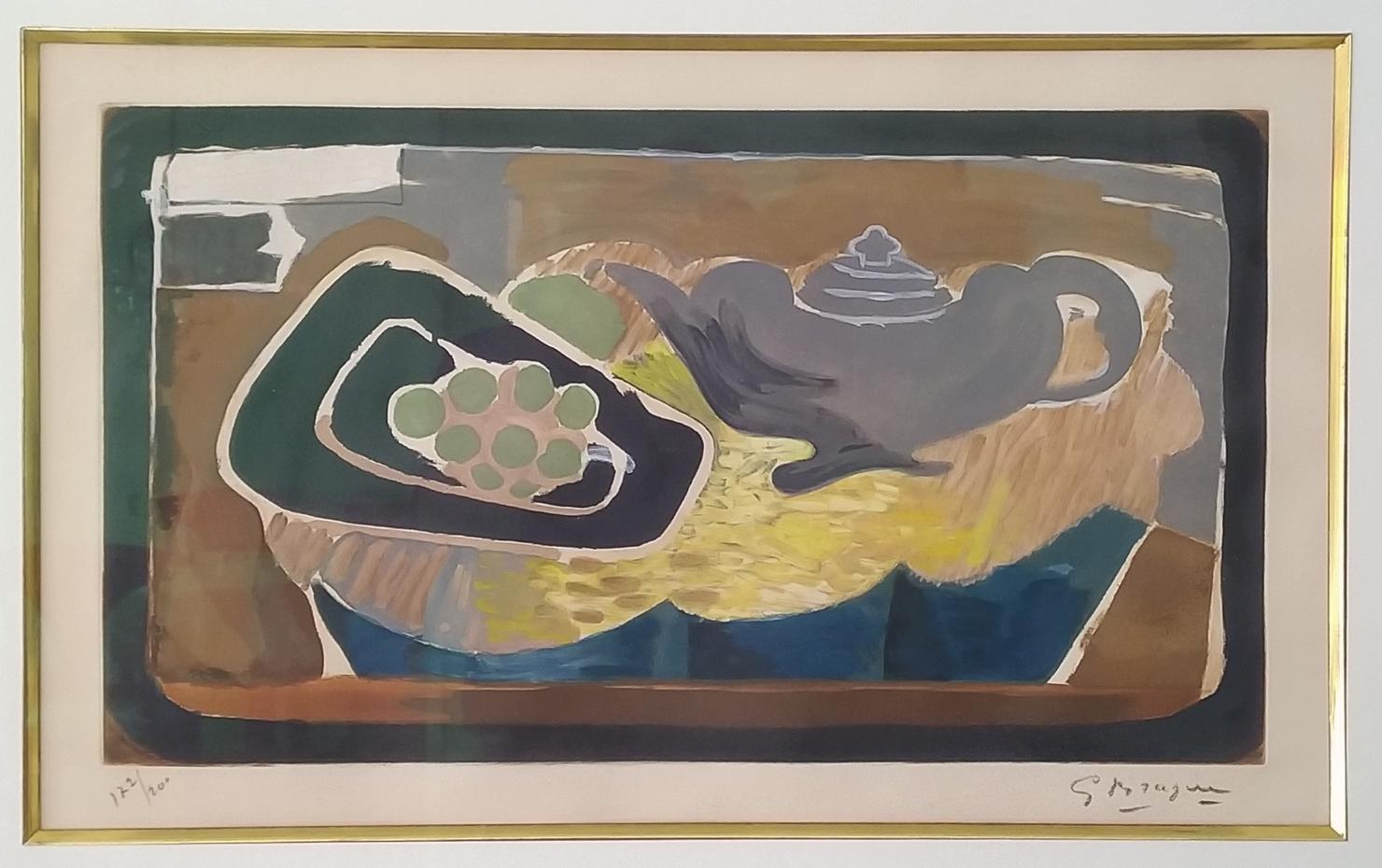

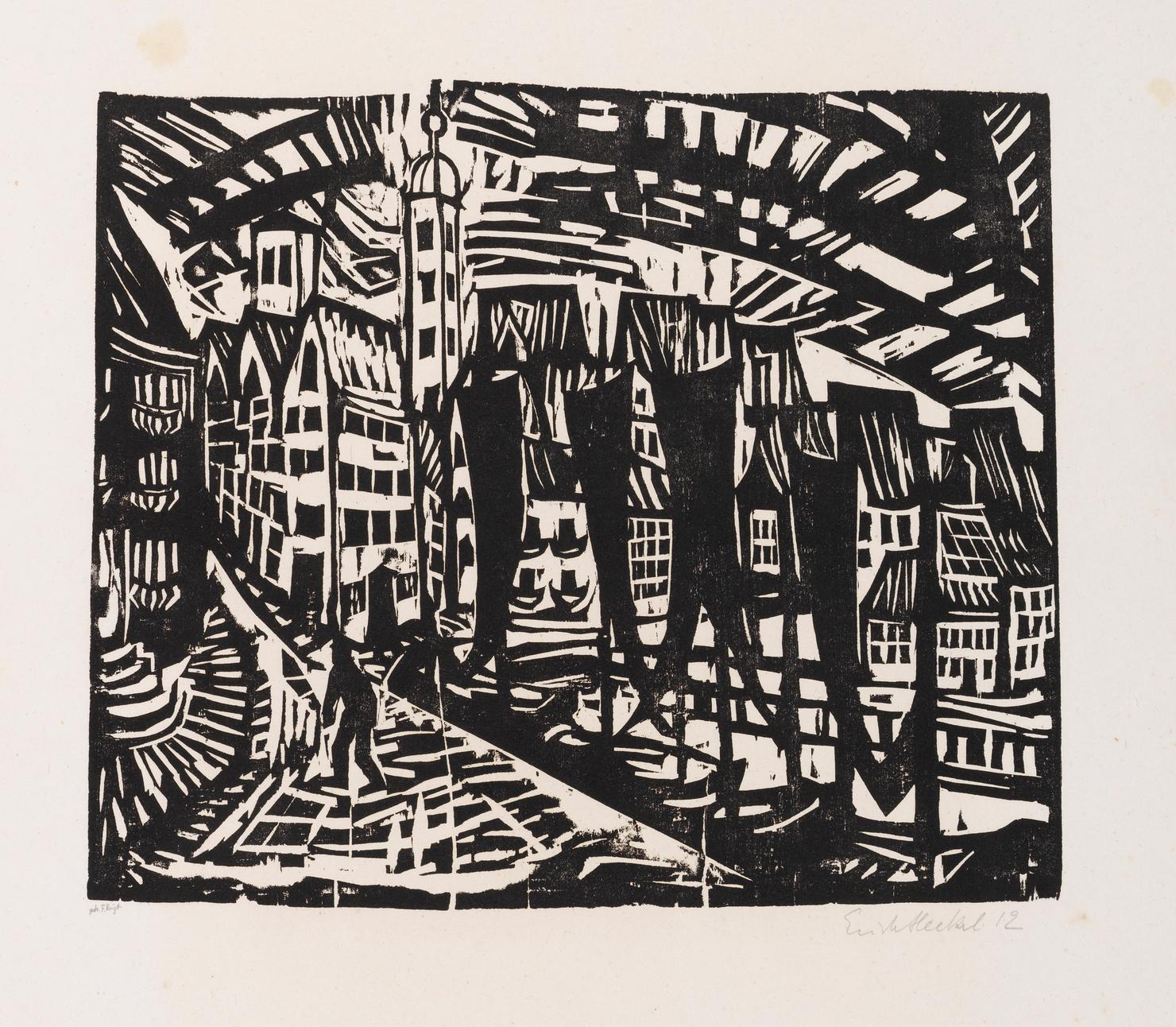

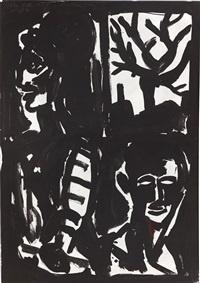

Holzschnitt.

Ebner/Gabelmann 533 H B, Dube H 243 B (von B). Signiert und datiert. Mit der handschriftlichen Bezeichnung des Druckers "gedr. F. Voigt". Eines von 40 Exemplaren. Auf Velin. 30,1 x 36,5 cm (11,8 x 14,3 in). Blattgröße: 61 x 51 cm (24 x 20 in).

Gedruckt von Fritz Voigt, Berlin, und herausgegeben von J.B. Neumann, Berlin. Blatt 1 der Mappe "Elf Holzschnitte, 1912-1919, Erich Heckel bei J.B. Neumann", Berlin 1921.

• Aus der gesuchten Berliner "Brücke"-Zeit.

• Aus einem reichen Liniengeflecht und nahezu geometrischen Formen schafft Heckel eine rhythmisierte, mosaikähnliche Darstellung der Altstadt Stralsunds.

• Stralsund besucht der Künstler 1912 auf dem Weg zur Insel Hiddensee, wo Heckel 1912 mit seiner Lebensgefährtin Siddi die Sommermonate verbringt.

• Weitere Exemplare dieses Holzschnitts sind Teil bedeutender musealer Sammlungen, darunter das Städel Museum, Frankfurt a. Main, und das Brooklyn Museum, New York.

• Im selben Jahr schafft Heckel auch ein gleichnamiges, motivisch eng verwandtes Gemälde (Voigt 1912/26).

PROVENIENZ: Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, Würzburg (mit dem Sammlerstempel, Lugt 6032).

AUSSTELLUNG: Schleswig-Holsteinisches Landesmuseum, Schloss Gottorf, Schleswig (Dauerleihgabe aus der Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, 1995-2001).

Kunstmuseum Moritzburg, Halle an der Saale (Dauerleihgabe aus der Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, 2001-2017).

Buchheim Museum, Bernried (Dauerleihgabe aus der Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, 2017-2022).

LITERATUR: Heinz Spielmann (Hrsg.), Die Maler der Brücke. Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, Stuttgart 1995, S. 199, SHG-Nr. 246 (m. Abb.).

Hermann Gerlinger, Katja Schneider (Hrsg.), Die Maler der Brücke. Bestandskatalog Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, Halle (Saale) 2005, S. 194, SHG-Nr. 434 (m. Abb.).

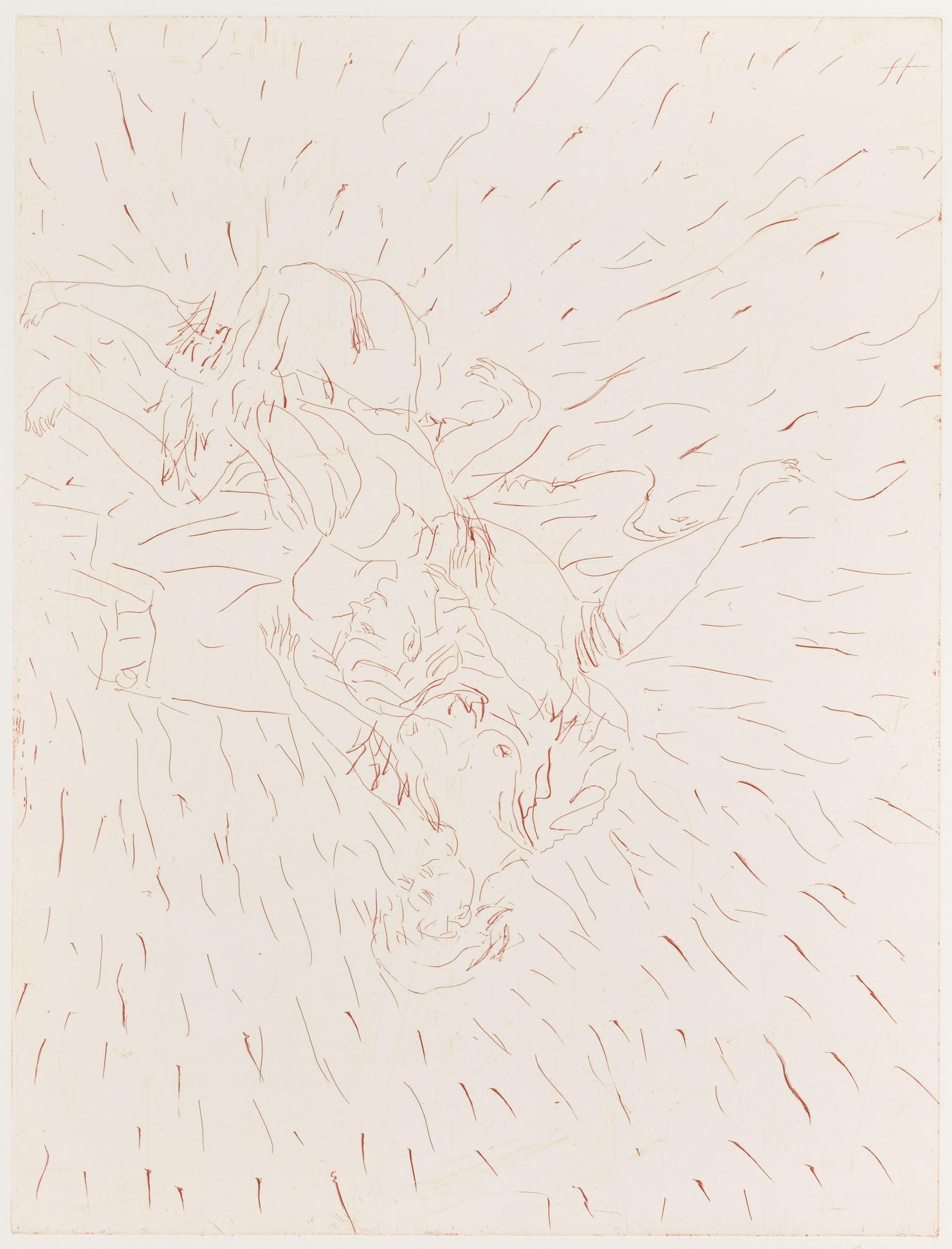

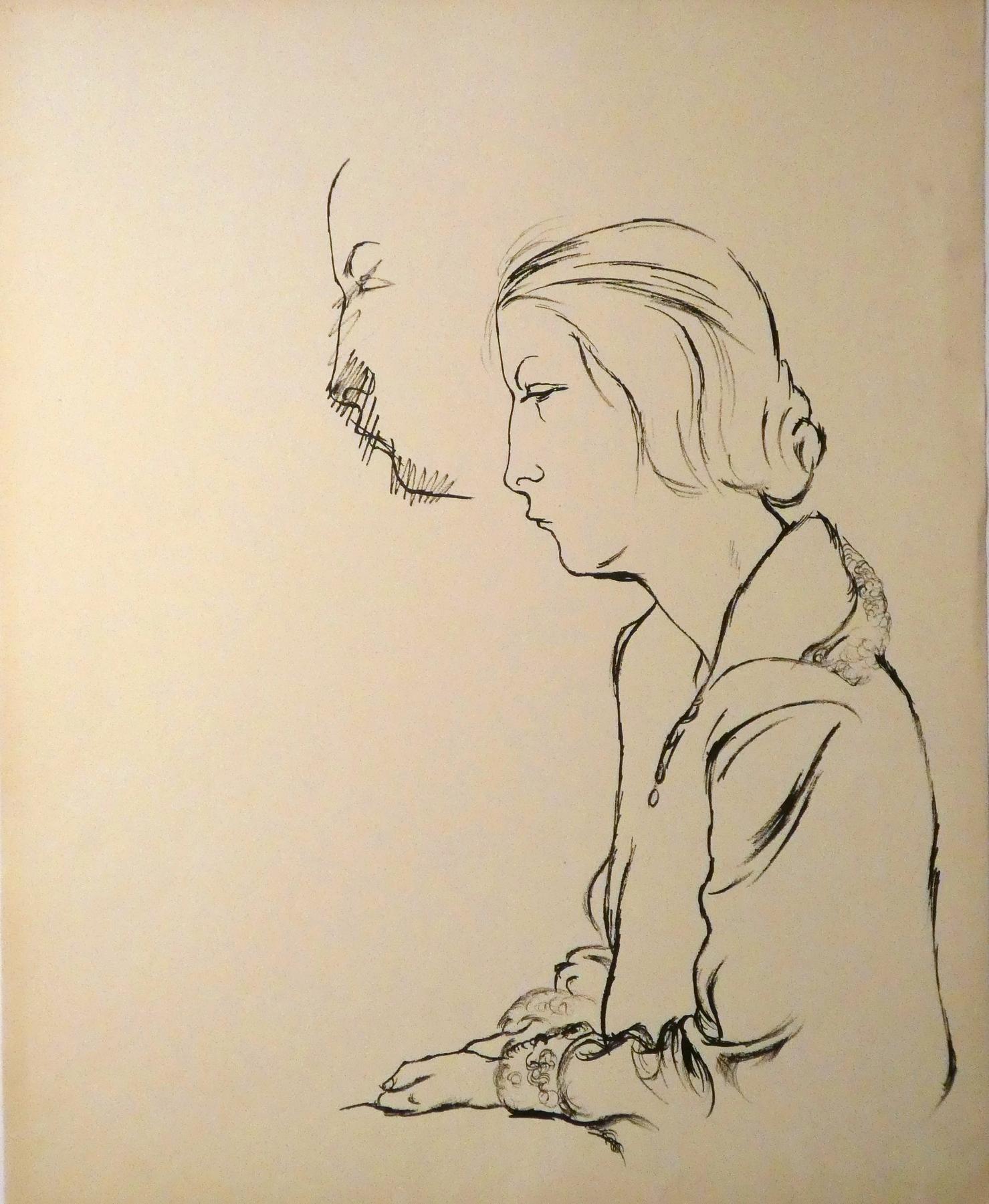

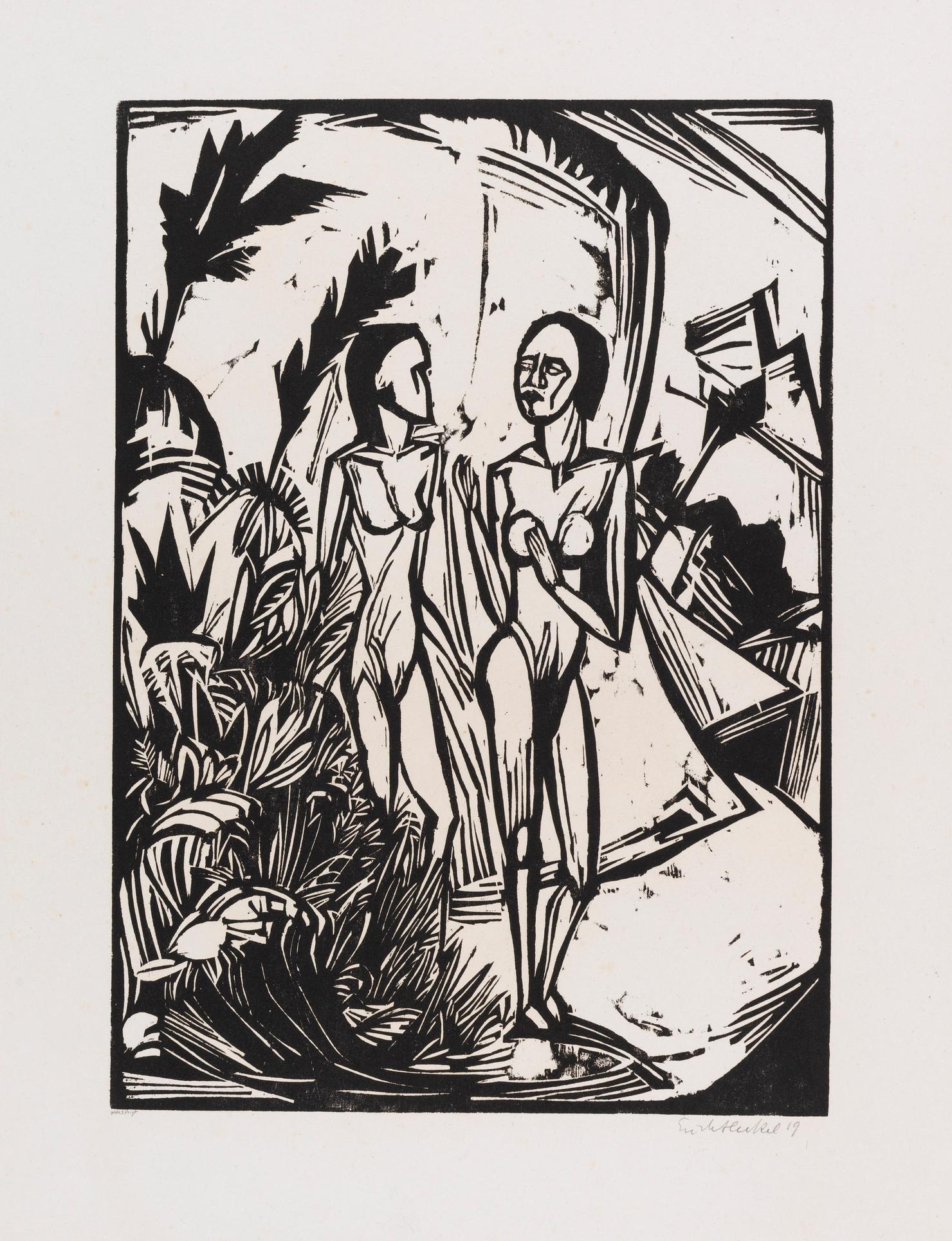

Holzschnitt.

Ebner/Gabelmann 743 B (von B). Dube 320 I B (von II). Signiert und datiert. Bezeichnet "gedr. F. Voigt". Eines von 40 Exemplaren. Auf Velin. 46,1 x 32,7 cm (18,1 x 12,8 in). Papier: 60,8 x 51,5 cm (23,9 x 20,1 in).

Gedruckt von Fritz Voigt, Berlin. Blatt 10 aus der Mappe "Elf Holzschnitte, 1912-1919, Erich Heckel bei J.B. Neumann", Berlin 1921 [EH].

PROVENIENZ: Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, Würzburg (mit dem Sammlerstempel, Lugt 6032).

LITERATUR: Heinz Spielmann (Hrsg.), Die Maler der Brücke. Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, Stuttgart 1995, S. 306, SHG-Nr. 467 (m. Abb.).

Hermann Gerlinger, Katja Schneider (Hrsg.), Die Maler der Brücke. Bestandskatalog Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, Halle (Saale) 2005, S. 216, SHG-Nr. 488 (m. Abb.).

Holzschnitt.

Ebner Gabelmann 730 H B (von B). Dube H 314 B (von B) . Signiert und datiert. Bezeichnet "gedr. F. Voigt". Eines von 40 Exemplaren. Auf Velin. 45,8 x 32,3 cm (18 x 12,7 in). Papier: 61,8 x 50,8 cm (24,3 x 20 in).

Gedruckt von Fritz Voigt, Berlin. Blatt 9 aus der Mappe "Elf Holzschnitte, 1912-1919, Erich Heckel bei J.B. Neumann", Berlin 1921.

PROVENIENZ: Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, Würzburg (mit dem Sammlerstempel, Lugt 6032).

AUSSTELLUNG: Schleswig-Holsteinisches Landesmuseum, Schloss Gottorf, Schleswig (Dauerleihgabe aus der Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, 1995-2001).

Kunstmuseum Moritzburg, Halle an der Saale (Dauerleihgabe aus der Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, 2001-2017).

Buchheim Museum, Bernried (Dauerleihgabe aus der Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, 2017-2022).

LITERATUR: Heinz Spielmann (Hrsg.), Die Maler der Brücke. Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, Stuttgart 1995, S. 304, SHG-Nr. 462 (m. Abb.).

Hermann Gerlinger, Katja Schneider (Hrsg.), Die Maler der Brücke. Bestandskatalog Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, Halle (Saale) 2005, S. 214, SHG-Nr. 482 (m. Abb.).

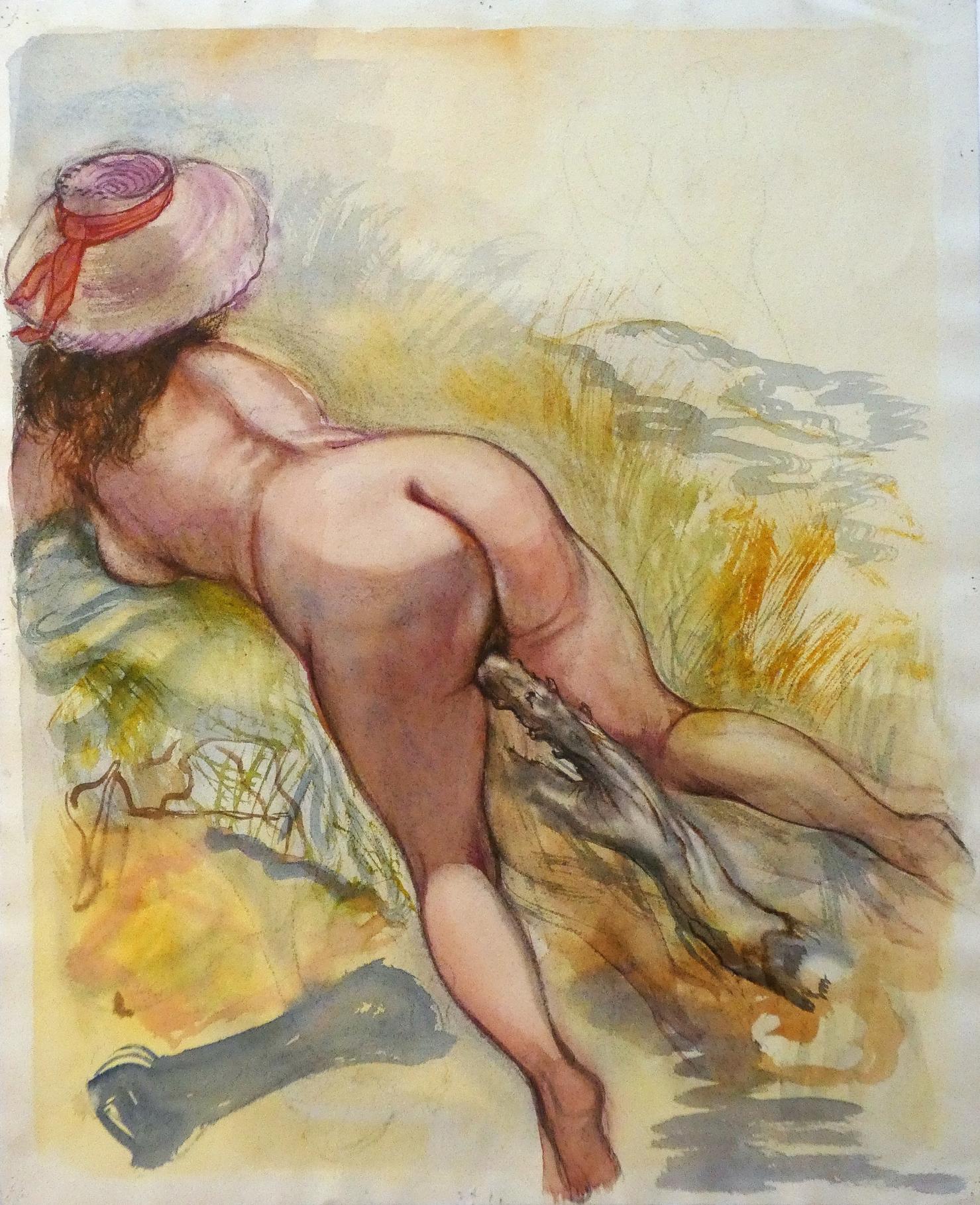

Holzschnitt.

Ebner/Gabelmann 589 H a B (von b). Dube H 258 a B (von b). Signiert und datiert. Bezeichnet "gedr. F. Voigt". Aus einer Auflage von 40 Exemplaren. Auf Velin. 49,9 x 32,3 cm (19,6 x 12,7 in). Papier: 61 x 51,3 cm (24 x 20,1 in).

Gedruckt von Fritz Voigt, Berlin. Blatt 2 aus der die Mappe "Elf Holzschnitte, 1912-1919, Erich Heckel bei J.B. Neumann", Berlin 1921.

• Historisch bedeutendes Entstehungsjahr: 1913 gibt die Künstlergruppe aufgrund interner Unstimmigkeiten ihre Auflösung bekannt.

• Weitere Exemplare dieses Holzschnitts sind Teil bedeutender musealer Sammlungen, darunter das Museum of Modern Art, New York, das Städel Museum, Frankfurt a. Main, und das Brücke-Museum, Berlin.

• Im darauffolgenden Jahr schafft Heckel u. a. auch das motivisch eng verwandte Gemälde "Badende am Stein" (Hüneke 1914-22).

• Badende, Akte im Freien und ihre ungezwungene Nacktheit gehören seit der Dresdener Schaffenszeit an den Moritzburger Teichen zu den Hauptmotiven Heckels und der "Brücke"-Künstler.

PROVENIENZ: Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, Würzburg (mit dem Sammlerstempel, Lugt 6032).

AUSSTELLUNG: Schleswig-Holsteinisches Landesmuseum, Schloss Gottorf, Schleswig (Dauerleihgabe aus der Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, 1995-2001).

Kunstmuseum Moritzburg, Halle an der Saale (Dauerleihgabe aus der Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, 2001-2017).

Buchheim Museum, Bernried (Dauerleihgabe aus der Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, 2017-2022).

LITERATUR: Heinz Spielmann (Hrsg.), Die Maler der Brücke. Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, Stuttgart 1995, S. 291, SHG-Nr. 429 (m. Abb., S. 290).

Hermann Gerlinger, Katja Schneider (Hrsg.), Die Maler der Brücke. Bestandskatalog Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, Halle (Saale) 2005, S. 200, SHG-Nr. 447 (m. Abb.).

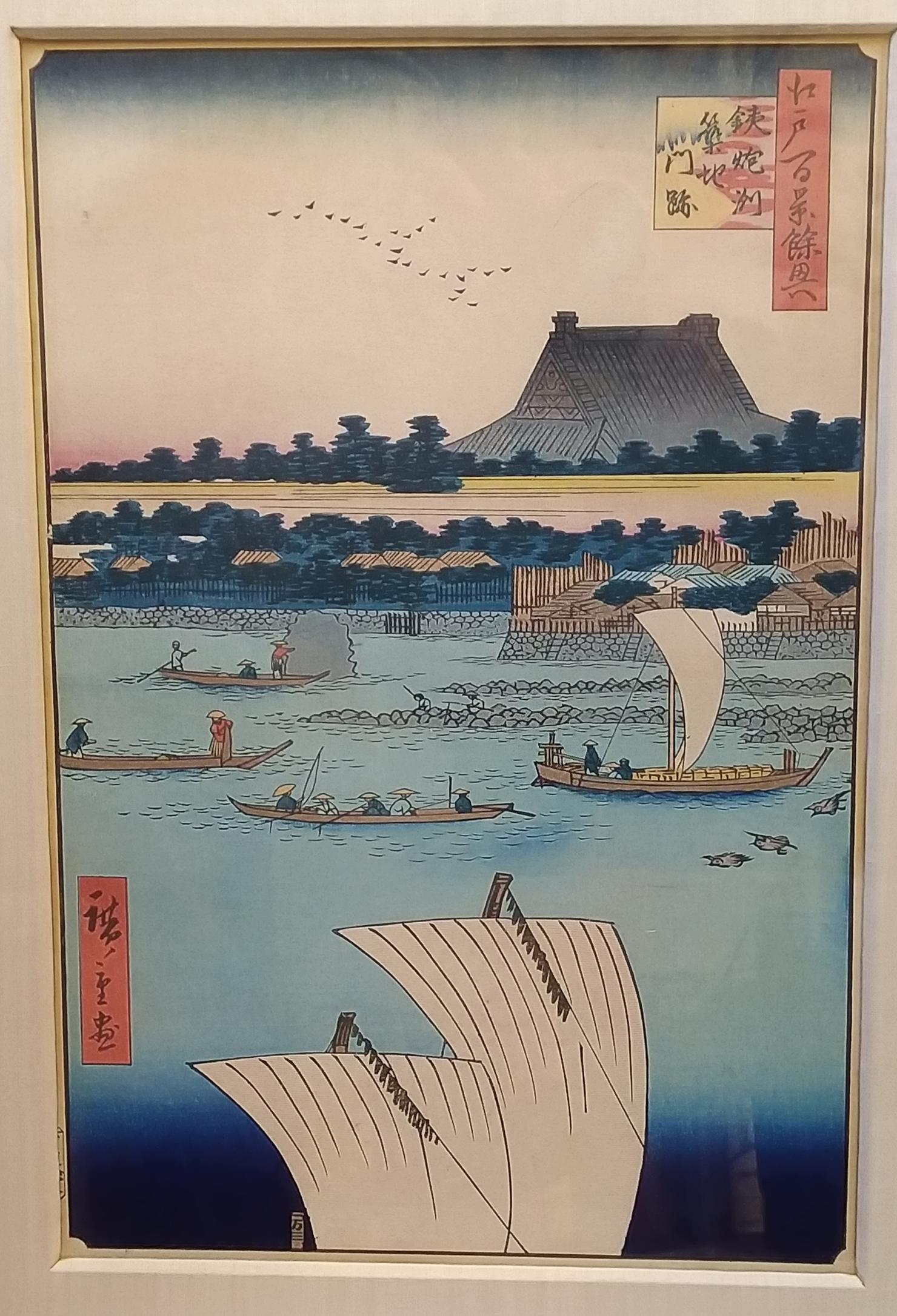

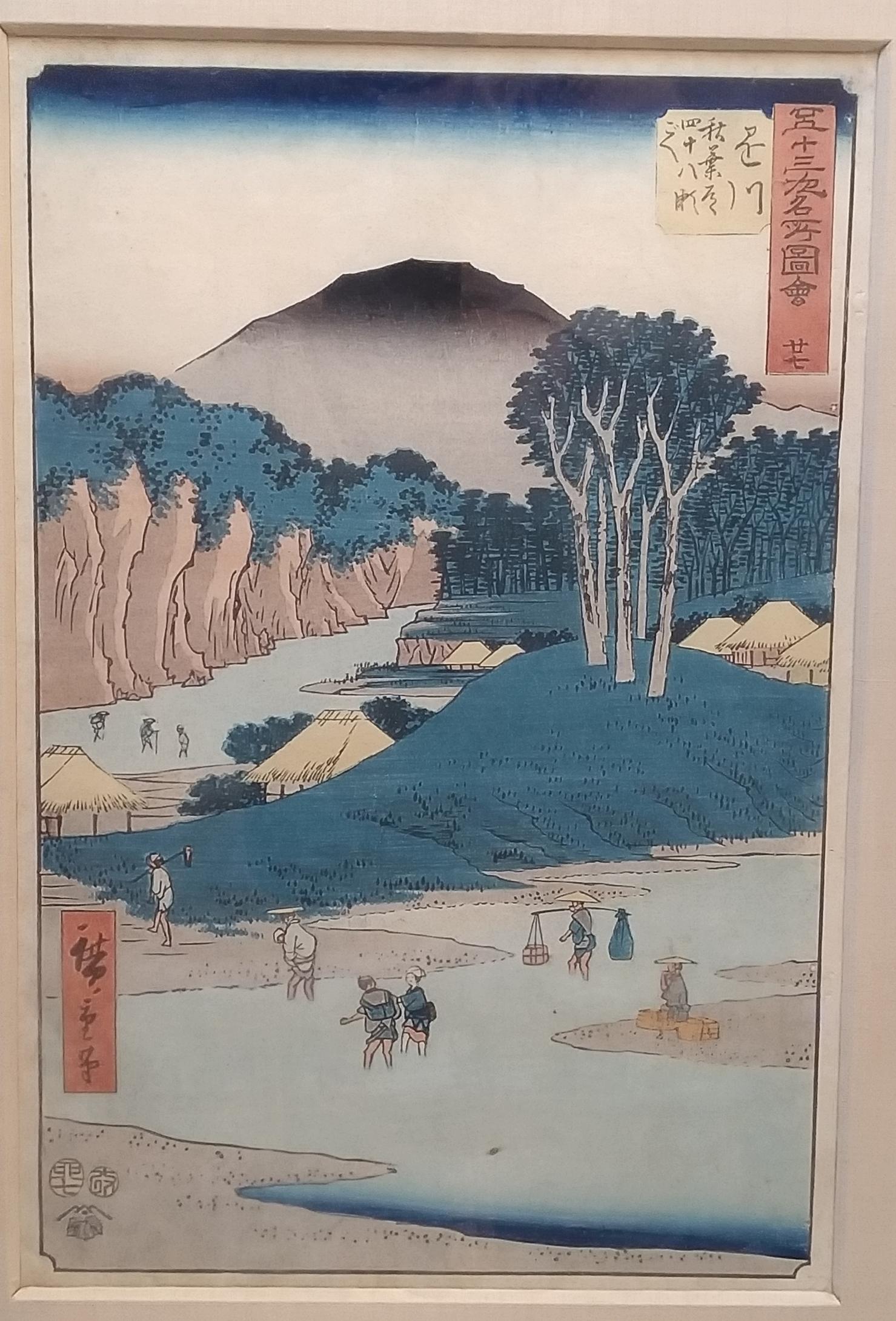

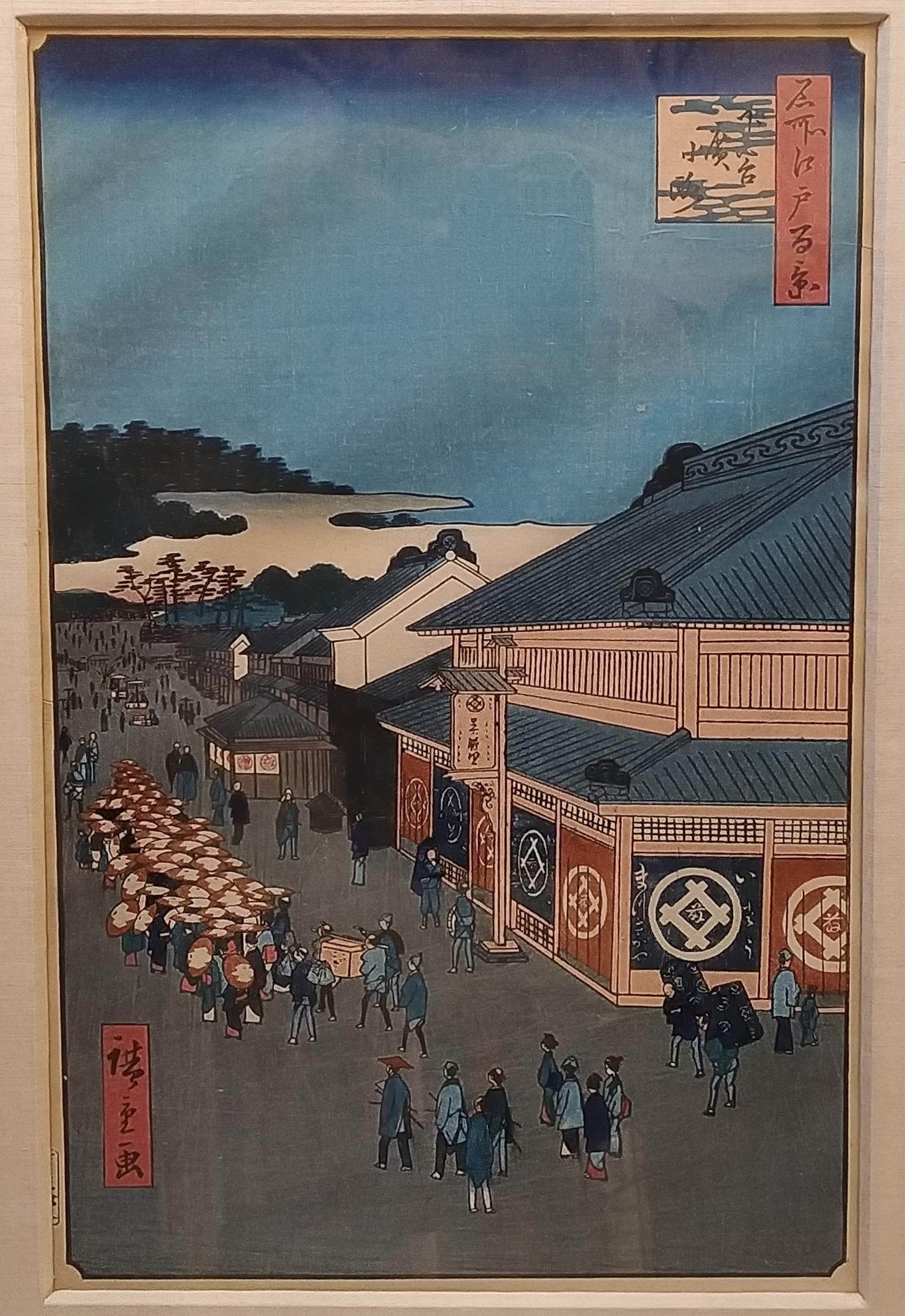

Die 53 Stationen des Tōkaidō (jap. 東海道五十三次之内, Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi), bekannt als Die 53 Stationen des Tōkaidō (Hoeidō-Ausgabe bzw. Hoeidō-Edition) (東海道五十三次之内保永堂版, Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi Hoeidō-ban), ist eine Serie von Farbholzschnitten, die in der ersten Hälfte der 1830er Jahre von dem japanischen Künstler Utagawa Hiroshige entworfen wurde. Mit den Entwürfen für diese Serie begründete Hiroshige seinen Ruf als bedeutendster Landschaftskünstler Japans im Bereich des Farbholzschnitts während der letzten Jahrzehnte der Edo-Zeit. Benannt ist die Serie nach dem Serientitel und dem Zusatz Hoeidō, dem registrierten Firmennamen des Verlegers Takenouchi Magohachi, der für die Produktion des größten Teils der Drucke verantwortlich zeichnete.

Die Hoeidō-Ausgabe war die erste Serie Hiroshiges mit dem Titel Die 53 Stationen des Tōkaidō. Bis zum Tod des Künstlers im Jahr 1858 folgten mindestens neun Serien mit demselben Titel und mindestens 13 weitere, die den Tōkaidō und dessen Stationen zum Thema hatten.

Die Serie umfasst 55 Drucke, beziehungsweise, mit den späteren zweiten Versionen von sechs Drucken, insgesamt 61 Blätter. Herausgegeben wurde die Serie zunächst gemeinsam von den beiden Verlegern Tsuruya Kiemon und Takenouchi Magohachi. Nach der Veröffentlichung von elf gemeinsam produzierten Drucken und einem nur unter seinem Namen erschienenen Druck schied Tsuruya Kiemon aus unbekannten Gründen als Herausgeber aus und Takenouchi Magohachi führte das Projekt allein weiter. Vor dem Erscheinen der 53 Stationen des Tōkaidō war Hiroshige ein weitgehend unbekannter Farbholzschnittkünstler. Die Beliebtheit der Drucke und der damit verbundene Verkaufserfolg machten ihn hinter Kunisada und Kuniyoshi zum beliebtesten Farbholzschnittkünstler seiner Zeit. Die Drucke der Serie erfuhren zahlreiche Neuauflagen und wurden so lange nachgedruckt, bis die ersten Druckplatten verschlissen waren und durch neue ersetzt werden mussten. Bereits in der Meiji-Zeit existierten viele unterschiedliche Versionen von verschiedenen Verlegern. Mit der Entdeckung japanischer Kunst durch westliche Sammler, zunächst aus den USA, dann auch aus Frankreich, Großbritannien und Deutschland, erlangten die Drucke Hiroshiges, und insbesondere die Drucke seiner ersten Serie Die 53 Stationen der Tōkaidō, im Westen Bekanntheit. Die Serie enthält einige der besten Arbeiten des Künstlers, wie zum Beispiel die Stationen Mariko, Kambara, Shōno und Kameyama. Diese Drucke zählen neben Hokusais Großer Welle zu den bekanntesten japanischen Farbholzschnitten außerhalb Japans.

Hokusai und Hiroshige erzielten in ihren Holzschnitten Farbverläufe oder „bokashi“ mithilfe einer sorgfältigen und innovativen Technik, die mehrere Schritte umfasste:

1. **Farbauftrag**: Anstatt die Farbe gleichmäßig auf den Holzschnitt aufzutragen, verwendete der Drucker einen Pinsel, um unterschiedliche Mengen an Farbe aufzutragen und so einen Farbverlauf zu erzeugen. Der Pinsel konnte mit unterschiedlichen Mengen an Farbe und Wasser getränkt werden, was einen allmählichen Farbübergang ermöglichte.

2. **Nasses Papier**: Manchmal wurde das Papier vor dem Druck angefeuchtet. Dadurch konnte die Tinte gleichmäßig verlaufen und weichere Übergänge zwischen den Farben erzeugen.

3. **Mehrere Blöcke**: Hokusai und andere Ukiyo-e-Künstler verwendeten oft mehrere Holzblöcke für einen einzigen Druck, von denen jeder für eine andere Farbe oder Schattierung geschnitzt wurde. Durch sorgfältiges Ausrichten dieser Blöcke konnten sie komplexe Farbverläufe und Schattierungen erzielen.

4. **Handtechniken**: Durch zusätzliche Handtechniken, wie das mehr oder weniger starke Reiben des Papiers in bestimmten Bereichen, konnte auch die Menge der übertragenen Tinte beeinflusst und der Verlaufseffekt verstärkt werden.

5. **Versuch und Irrtum**: Der Prozess erforderte viel Versuch und Irrtum. Drucker fertigten oft mehrere Testdrucke an, um den richtigen Verlauf zu erzielen, bevor sie die endgültige Version produzierten.

Informationen über Hiroshiges und Hokusais Techniken zur Erstellung von Farbverläufen in seinen Drucken, die als „Bokashi“ bekannt sind, finden sich in mehreren maßgeblichen Quellen zum japanischen Holzschnitt und zur Ukiyo-e-Kunst. Zu den wichtigsten Referenzen gehören:

1. **„The Art of Japanese Printmaking“** von Asahi News Service: Dieses Buch bietet detaillierte Einblicke in traditionelle japanische Drucktechniken, einschließlich Bokashi.

2. **„Hokusai: Genius of the Japanese Ukiyo-e“** von Seiji Nagata: Dieses umfassende Werk befasst sich mit Hokusais Leben, seinen Techniken und seinen Beiträgen zur Ukiyo-e, einschließlich seiner innovativen Verwendung von Farbverläufen.

3. **Museumskataloge und Ausstellungsführer**: Institutionen wie das British Museum und das Metropolitan Museum of Art haben umfangreiche Kataloge und Führer zu ihren Ukiyo-e-Sammlungen veröffentlicht, die auch technische Erläuterungen zu Hokusais Werken enthalten.

4. **Wissenschaftliche Zeitschriften**: Artikel in Zeitschriften wie „Impressions“, der Zeitschrift der Ukiyo-e Society of America, befassen sich häufig mit bestimmten Techniken, die von Künstlern wie Hokusai verwendet wurden.

Veröffentlichung

Hiroshige war um 1830 ein weitgehend unbekannter Künstler, der bis dahin nur wenige Aufträge für den Entwurf von Farbholzschnitten erhalten hatte. Um 1830 übertrug ihm der Verleger Kawaguchiya Shōzō den Auftrag, eine Serie von großformatigen Drucken (das heißt Drucke im ōban-Format) von Ansichten bekannter Orte in Edo zu gestalten („Berühmte Ansichten der Osthauptstadt“, Tōto meisho, 東都名所). Die Serie war kein überragender Erfolg, erlebte jedoch bereits mehrere Auflagen, wie unterschiedliche Druckzustände belegen. Die Serie, die Hiroshige als Künstler der Landschaftsdrucke (fūkeiga, 風景画) bekannt machte, war die Serie dem Titel „Die 53 Stationen des Tōkaidō“ (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi).

Zu Beginn der 1830er Jahre erschienen die ersten Drucke dieser Serie und waren ebenso wie die vorhergehende Serie im ōban-Querformat angelegt. Gemeinsame Verleger der ersten elf Drucke waren Tsuruya Kiemon und Takenouchi Magohachi, der Druck der Station Okabe wurde alleine von Tsuruya Kiemon herausgegeben und die weiteren 43 Drucke produzierte Takenouchi Magohachi alleine. Wer die Idee für dieses Projekt hatte und wer wen zuerst angesprochen hat, ist nicht mehr zu klären. Für Takenouchi Magohachi war es das erste Projekt als Verleger, Tsuruya Kiemon war ein alteingesessenes Verlagshaus. Nach Tsuruya Kiemons Ausscheiden, über dessen Gründe nichts bekannt ist, führte Takenouchi Magohachi das Projekt alleine fort.

Titel auf dem Vorsatzblatt, Vorwort und Inhaltsverzeichnis der ersten Gesamtausgabe

Die Drucke zeigen Szenen rund um die Stationen des Tōkaidō, der damals wichtigsten Überlandverbindung von Edo nach Kyōto, und deren umliegende Landschaften sowie zusätzlich den Startpunkt Nihonbashi in Edo und die Endstation bei Kyōto (damals auch Keishi genannt). Sie sind nicht in der Reihenfolge der Stationen entstanden; allenfalls orientierte sich die Reihenfolge der Entwürfe lose an der Abfolge der Raststationen.

Beim Publikum und den zeitgenössischen Kritikern fanden die Drucke großen Anklang und wurden, nachdem alle Einzeldrucke erschienen waren, von Takenouchi Magohachi in zwei Bänden in Buchform herausgegeben. Der Titel auf dem Einband der Bücher lautete „Aufeinanderfolgende Bilder der 53 Stationen des Tōkaidō“ (Shinkei Tōkaidō gojūsan eki tsuzukie, 真景東海道五十三駅続畫). Der Serientitel auf den Drucken selbst blieb unverändert. Allerdings waren die Drucke in den beiden Bänden mittig vertikal gefaltet, da die Bücher im chūban-Format (halbes ōban-Format) erschienen. Viele der heute erhaltenen Drucke der Serie weisen diese Mittelfalte als Hinweis darauf aus, dass sie ursprünglich aus einem dieser Bücher stammen. Heute ist kein vollständiges Exemplar der Erstauflage dieser Bücher mehr bekannt.

Schätzungen zufolge wurden von einzelnen Blättern der Serie bis zu 25.000 Exemplare von den ersten Druckplatten gefertigt, bis diese nicht mehr zu gebrauchen waren. Bereits im 19. Jahrhundert waren neue Platten geschnitten worden, um weitere Auflagen anzufertigen. Im 20. Jahrhundert erfolgten weitere Neuauflagen und selbst im 3. Jahrtausend werden noch immer Drucke dieser Serie als Farbholzschnitte und Reproduktionen verkauft.

Ein größerer Teil der Drucke wurde nach der Erstveröffentlichung einer Überarbeitung unterzogen (Änderung der Farbpalette, Ausfüllen kleiner Fehlstellen, Weglassen einzelner Konturlinien etc.), so dass sie in zahlreichen unterschiedlichen Varianten erhalten sind. Ob diese Veränderungen auf Überlegungen Hiroshiges oder des Verlegers oder gar beider zurückzuführen ist, ist heute nicht mehr feststellbar. Gesichert ist, dass einige der Änderungen bereits nach der ersten Auflage erfolgt sein müssen, da einzelne Blätter im Zustand der Erstauflage extrem selten sind. Von sechs Stationen wurde in der zweiten Hälfte der 1830er Jahre eine zweite Druckversion angefertigt, die möglicherweise verlorengegangene oder beschädigte Druckplatten ersetzten. Diese neuen sind den vorhergehenden Versionen ähnlich, aber nicht mit ihnen identisch.

Der kommerzielle Erfolg der Serie Hiroshiges stand im engen Zusammenhang mit dem immens angewachsenen Reiseverkehr in Japan in den ersten Jahrzehnten des 19. Jahrhunderts, die eine Gesellschaft hervorgebracht hatten, die „süchtig nach Reisen und verrückt nach Souvenirs“ war.

Unmittelbarer Vorgänger von Hiroshiges Serie waren Katsushika Hokusais Drucke der „36 Ansichten des Berges Fuji“, die in ihrem Format und der Bildgestaltung, Darstellung von Menschen, eingebettet in eine sie umgebende Landschaft, Vorbildcharakter sowohl für Hiroshige als auch andere Landschaftsmaler seiner Zeit hatten.

Mit seiner Serie traf Hiroshige jedoch noch mehr als Hokusai den Geschmack breiter Bevölkerungsschichten und setzte den Gedanken des Ukiyo als der „heiteren, vergänglichen Welt“ vollendet in den japanischen Landschaftsdruck um. Neu an Hiroshiges künstlerischer Landschaftsauffassung war nicht, dass er „lebendige Straßenszenen mit geschäftigen Menschen aus dem einfachen Volk (zum) Gegenstand der künstlerischen Auseinandersetzung“ machte. Solche Genreszenen waren zuvor bereits unter anderem von Utagawa Toyohiro und Hokusai gezeichnet worden. Neu an Hiroshiges Bildern war die harmonische Eingliederung der Menschendarstellung in weitläufige Landschaften. Er gestaltete lyrische Bilder, in denen der Betrachter die Stimmung der Natur ungetrübt von philosophischem Nachsinnen über Natur und Mensch unmittelbar wahrnehmen konnte. Die Drucke der Serie waren durchdrungen von expressiver poetischer Sensibilität. Hiroshiges innovativer Stil und die Wahl des horizontalen ōban-Formats stellten einen neuen Schwerpunkt in der Auffassung des Tōkaidō dar und präsentierten eine neue Art des Landschaftsdruckes. Ihre andauernde Popularität und ihr Einfluss auf andere Künstler sind die Gründe für Hiroshiges Ruhm.

Entstehungsgeschichte

Zur Entstehung der Serie hatte Hiroshige III., Schüler Hiroshiges I. und zweiter Ehemann von dessen Tochter, im Jahr 1894 kurz vor seinem Tod beiläufig in einem Zeitungsinterview geäußert, dass die Drucke der Serie auf Entwürfe zurückzuführen seien, die Hiroshige I. als Angehöriger einer offiziellen Delegation des Shōgun angefertigt habe. Die Delegation habe im Jahr 1832 den Auftrag gehabt, ein Pferd als Geschenk des Shōgun Tokugawa Ienari von Edo an den Kaiserhof in Kyōto zu überbringen. Unterwegs habe Hiroshige seine Reiseeindrücke in Skizzen festgehalten und nach seiner Rückkehr nach Edo im 9. Monat des Jahres Tenpō 3 (entspricht in etwa dem September des Jahres 1832) dem Verleger Takenouchi Magohachi angeboten, die Skizzen als Vorlagen für eine Farbholzschnittserie umzuarbeiten. Diese Geschichte übernahm zunächst Iijima Kyōshin in sein 1894 erschienenes Buch „Biografien der Ukiyo-e-Künstler der Utagawa-Schule“ (Utagawa retsuden, 浮世絵師歌川列伝).[23] Dann wurde sie 1930 von Minoru Uchida in dessen erste umfassende Biografie Hiroshiges aufgenommen. Von da an fand sie sich ungeprüft in der gesamten Literatur, die über Hiroshige erschienen ist. Zum Teil wurde sie soweit ausgeschmückt, dass Hiroshige möglicherweise sogar im Auftrag des Shōgun seine Skizzen angefertigt habe.

Suzuki äußerte 1970 in seinem Buch „Hiroshige“ erste Zweifel an dieser Entstehungsgeschichte, indem er auf die Ähnlichkeit der Hiroshige-Drucke der Stationen Ishibe und Kanaya mit den entsprechenden Abbildungen im bereits 1797 erschienenen Tokaidō meisho zue hinwies. Matthi Forrer griff 1997 diese Zweifel auf und wies auf die Unmöglichkeit hin, dass die Serie in 15 Monaten von Oktober 1832 bis zum Ende des Jahres 1834 fertiggestellt worden sein konnte. Weitere Zweifel äußerte Timothy Clark 2004 und bezog sich dabei auf einen 1998 von Jun’ichi Okubo in Japan veröffentlichten Artikel. Clark hält die Geschichte von der Beteiligung Hiroshiges an einer offiziellen Delegation für einen Schwindel. 2004 erschien die bislang umfassendste Monografie über Hiroshiges erste Tōkaidō-Serie von Jūzō Suzuki, Yaeko Kimura und Jun’ichi Okubo, Hiroshige Tōkaidō gojūsantsugi: Hoeidō-ban. Die Autoren wiesen darin nach, dass 26 der 55 Drucke der Serie auf zeitgenössische Vorlagen anderer Künstler zurückzuführen sind. Zudem sei eine Beteiligung von Hiroshige (bzw. Andō als seinem bürgerlichen Namen) an einer shōgunalen Delegation in den erhaltenen Akten nicht verzeichnet. Ebenso wenig ist eine solche Reise im noch zu Lebzeiten Hiroshiges erschienenen Ukiyo-e ruikō („Verschiedene Gedanken über Ukiyo-e“, 浮世絵類考), einer Art zeitgenössischen Who’s who der Farbholzschnittkünstler, erwähnt. Dass die Drucke der Serie nicht auf eigene Skizzen Hiroshiges zurückzuführen seien, sondern auf Vorlagen zeitgenössischer Reiseführer, äußerte Andreas Marks im Zusammenhang mit seinen Beschreibungen der Verlegertätigkeit Takenouchi Magohachis in den Jahren 2008 und 2010. Nachdem Marks für sein Buch Kunisada’s Tōkaidō weitere Bücher nachweisen konnte, aus denen Hiroshige Anregungen für die Gestaltung seiner Drucke entnommen hat, kommt er zu dem Ergebnis, dass die Geschichte von der Entstehung der Drucke als Reiseskizzen nicht länger aufrechtzuerhalten sei.

Datierung

In Übereinstimmung mit der überlieferten Entstehungsgeschichte im Zusammenhang mit der im Dienste des Shōgun unternommenen Reise und der darin dokumentierten Rückkehr Hiroshiges nach Edo im September 1832 wird in der Literatur als Entstehungsjahr der ersten Drucke der Serie das Jahr 1832 angegeben. Das üblicherweise angegebene Datum für die Fertigstellung der Serie spätestens zum Jahresende 1833 folgt aus dem Vorwort des Autors Yomo no Takisui (andere Lesung des Namens: Yomo Ryūsai), das der ersten Gesamtausgabe vorangestellt und mit dem ersten Monat des Jahres Tenpō 5 (in etwa Januar 1834) datiert ist.

Matthi Forrer geht davon aus, dass das Datum der Fertigstellung durch das Vorwort der Gesamtausgabe korrekt angegeben ist, äußert jedoch Zweifel, ob eine Serie von 55 ōban-Drucken innerhalb von nur 15 Monaten zwischen Oktober 1832 und Dezember 1833 hätte fertiggestellt werden können. Keine andere Farbholzschnittserie im ōban-Format hatte in Japan bis dahin einen solchen Umfang gehabt. Der Verleger Takenouchi Magohachi war Sohn eines Pfandleihers und vor der Produktion der Hiroshige-Drucke nicht als Verleger in Erscheinung getreten. Seine finanziellen Ressourcen bzw. seine Kreditwürdigkeit waren nicht ausreichend, das erforderliche Kapital für die Druckplatten, das Papier, die Farben und die Entlohnung für Holzschneider, Drucker und Künstler sowie die Kosten für einen Laden zum Verkauf der Drucke in so kurzer Zeit aufzubringen. Auch wenn zu Beginn der Produktion mit Tsuruya Kiemon ein alteingesessener Verleger beteiligt war, erscheint nach Forrer eine solch kurze Zeitspanne von 15 Monaten außergewöhnlich kurz. Er folgert daraus, dass sich die Fertigstellung der Drucke über einen längeren Zeitraum erstreckt haben müsse und somit die ersten Drucke im Jahr 1831 oder sogar bereits 1830 erschienen sein müssten.

Jūzō Suzuki äußert darüber hinaus Zweifel am Datum der Fertigstellung der Serie zum Jahresende 1833. Ihm zufolge sei im Impressum der Gesamtausgabe als Adresse die Anschrift eines Ladens angegeben, den Takenouchi Magohachi nicht vor dem Neujahrstag 1836 eröffnet habe.

Suzuki ist ebenfalls davon überzeugt, dass Kunisadas bijin-Serie Tōkaidō Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi, bei deren Drucken der Hintergrund in 43 Fällen nach der Vorlage von Hiroshiges Serie gestaltet war, im Jahr 1833 begonnen und im Jahr 1835 vollendet worden war. Die Tatsache, dass 13 der Drucke von Kunisadas Serie einen Hintergrund haben, der von dem der Hiroshige-Drucke abweicht, interpretiert Suzuki so, dass Hiroshige seine Serie im Jahr 1835 noch nicht vollständig entworfen hatte. Kunisadas Verleger, Moriya Jihei und Sanoya Kihei, hätten jedoch darauf gedrängt, die Serie zu vollenden, und daher seien für die letzten, noch fehlenden Drucke Hintergründe aus dem Tokaidō meisho zue und ähnlichen Büchern ausgewählt worden.

Yaeko Kimura war die erste, die wissenschaftliche Nachforschungen zur Biografie Takenouchi Magohachis anstellte und dabei unter anderem die verschiedenen von ihm verwendeten Verlegersiegel verglich. Ihrer Ansicht nach könne eine Gesamtausgabe von Hiroshiges Tōkaidō nicht vor dem Neujahrstag 1836 erfolgt sein.

Da weitere Anhaltspunkte für die exakte Datierung der Drucke der Serie fehlen, kann ihre Entstehungszeit insgesamt nur ungefähr auf die erste Hälfte der 1830er Jahre eingegrenzt werden.

Bildgestaltung

Die Drucke sind im horizontalen (yoko-e) ōban-Format (ca. 39 × 26 cm) ausgeführt. Die bedruckte Fläche ist an allen vier Seiten mit einer dünnen schwarzen Linie von der unbedruckten Papierfläche abgegrenzt. Die Ecken sind nach innen abgerundet, so dass sich zusammen mit den jeweils ca. 1,5 cm breiten Rändern der Eindruck eines gerahmten Bildes ergibt. Bei vielen erhaltenen Drucken sind diese Ränder teilweise oder ganz bis auf den Druckrand beschnitten, wodurch der visuelle Eindruck der Drucke stark verändert wird. Besonders auffällig ist dies bei den Drucken der Stationen Hara und Kakegawa, bei denen ein Bildelement den oberen Rahmen „durchbricht“ und bei denen das durch den Beschnitt verursachte Fehlen dieses Elements die Gesamtkomposition des Druckes zerstört.

Auf allen Drucken sind in irgendeiner Form Reisende auf der Tōkai-Straße dargestellt. Abgebildet sind sie in Verbindung mit Wegen, Flusslandschaften, Bergen, Seen und Meerespanoramen sowie Szenen an oder in Raststationen oder Tempeln. Manchmal sind die Reisenden nur winzig klein in Gruppen als Staffage in der Landschaft zu sehen, manchmal sind sie gestalterisches Element der Drucke und mit individuellen Zügen gezeichnet. Die Drucke folgen keinem Programm, außer dem der Darstellung von Reisenden in unterschiedlichen Szenarien. Die auf den Drucken dargestellten Szenen zeigen keine bestimmte Jahreszeit, stattdessen wechseln sich die jahreszeitlichen Impressionen unsystematisch ab; abgebildet sind Szenen aus allen vier Jahreszeiten, mit Sonne, Regen oder Schneefall. Ebenso unterschiedlich und unsystematisch sind die in den Drucken zu erkennenden Tageszeiten: Zu sehen sind Szenen mit Sonnenauf- und -untergang sowie Szenen, die sich im Tagesverlauf oder im Einzelfall auch nachts abspielen.

An einer freien Stelle innerhalb der Bildkomposition befindet sich der Serientitel „Tōkaido gojūsan tsuki no uchi“. Die kanji des Titels sind in zwei bzw. drei Spalten geschrieben. In jeweils einem Fall ist der Titel in einer Spalte (Station Okabe) bzw. einer Zeile (Station Fuchū) geschrieben. Links vom Serientitel befindet sich leicht abgesetzt der Name der jeweiligen Station und wiederum davon links der Untertitel des jeweiligen Druckes; in einigen wenigen Fällen findet sich der Untertitel direkt unterhalb des Stationsnamens. Serientitel und Stationsnamen sind in Schwarz gedruckt; die Untertitel befinden sich in einer roten Kartusche, die in Negativ- oder Positivdruck ausgeführt ist.

Vom Serientitel abgesetzt, in vielen Fällen auf der gegenüberliegenden Seite des Blattes, ist die Signatur Hiroshiges (Hiroshige ga, 廣重画) in schwarzen kanji gedruckt. Unterhalb der Künstlersignatur findet sich ein rotes Verlegersiegel in unterschiedlichen Formen. Bei der zweiten Version des Druckes der Station Odawara findet sich ein zusätzliches rotes Verlegersiegel rechts oberhalb des Serientitels.

Das Zensursiegel kiwame (極 für ‚geprüft‘) befand sich ursprünglich bei allen Drucken auf dem linken unteren Randbereich der Blätter. Bei den ersten drei Stationen, Nihonbashi, Shinagawa und Kawasaki, sowie der Station Totsuka wurde nach der Überarbeitung der Bildkomposition das ursprüngliche gemeinsame Siegel der Verleger Senkakudō und Hoeidō durch ein kalebassenförmiges Siegel Hoeidōs mit einem integrierten Zensursiegel ersetzt und somit das kiwame-Siegel am linken Rand überflüssig. Auf den zweiten Versionen der Drucke der Stationen Kanagawa und Odawara ist das kiwame-Siegel ebenfalls vom linken Rand entfernt und durch ein Verlegersiegel mit integriertem kiwame-Siegel ersetzt worden.

Utagawa Hiroshige wurde 1797 als Andō Tokutarō (安藤 徳太郎) im Stadtviertel Yayosugashi (heute Marunouchi im Stadtbezirk Chiyoda) in Edo, dem heutigen Tokyo geboren. Seine Rufnamen in späteren Jahren waren Jūemon (重右衛門), Tokubē (徳兵衛) und eine Zeit lang Tetsuzō.

Hiroshige, bijin, Serie „Acht Ansichten - Frauen und Landschaften im Vergleich“, Anfang 1820er

Sein Vater war Mitsuemon Genemon, der von Andō Jūemon adoptiert worden war und von diesem das erbliche Amt eines untergeordneten Feuerwehroffiziers (Hikeshi Dōshin, „Verwalter der Vereinigung zur Feuerbekämpfung“) im Dienst des Bakufu übernommen hatte. Als Dienstmann des Bakufu war er Angehöriger des Samurai-Stands, sein Einsatzgebiet war das Viertel Yayosugashi.

Im Februar 1809 starb Tokutarōs Mutter. Im selben Monat übergab ihm sein Vater das Amt des Feuerwehroffiziers, wenige Monate später, gegen Ende des Jahres, starb auch der Vater. Von seinen drei Schwestern ist nur bekannt, dass die älteste bereits im Jahr 1800 verstorben war.

Tokutarō war Vorgesetzter einer kleinen Gruppe von Feuerwehrleuten. Seine Lebensverhältnisse waren bescheiden. Die mit dem Amt verbundene Besoldung war gerade ausreichend, zwei Menschen ein Jahr lang mit Reis zu versorgen. Die zehn Baracken, in denen die Feuerwehrabteilung untergebracht war, musste er sich mit 30 weiteren Offizieren und 300 Mannschaften und deren Familien teilen. Wie andere Angehörige des untersten Rangs der Samurai, den Gokenin, war er gezwungen, sich nach anderen Einkünften umzusehen. Gokenin-Familien beschäftigten sich oft mit Heimarbeit wie der Herstellung von Schirmen, Kisten und Holzsandalen.

Die Pflichten eines Feuerwehroffiziers in Edo zu Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts waren allem Anschein nach nicht besonders umfangreich und so hatte Tokutarō nebenbei Zeit, eine Lehre als Farbholzschnittzeichner zu beginnen. Weshalb er ausgerechnet diesen handwerklichen, bürgerlichen Beruf wählte, um ein Zubrot zu seinem Lebensunterhalt zu verdienen, ist völlig ungeklärt.

Inoffiziellen Malunterricht im Stil der Kanō-Schule hatte er bei einem seiner Vorgesetzten und Freund, Okajima Rinzō (oder Rinsai), erhalten. Für einen Angehörigen des Samurai-Stands, selbst des niedrigsten Rangs, wäre dies nichts Außergewöhnliches, da Kalligrafie und Grundkenntnisse des Malens zu deren Standardausbildung gehörten. Die Signatur eines angeblich aus seiner Kindheit erhaltenen Gemäldes, das eine Gesandtschaft des Königs der Ryūkyū-Inseln zum Shogun zeigt, und seine frühe außerordentliche zeichnerische Fähigkeit beweisen soll, ist nach Forrer zweifelhaft, und selbst wenn es Hiroshige zugeschrieben werden könnte, ließe es keine besondere Begabung erkennen.

Der Überlieferung nach bewarb sich Tokutarō zunächst um eine Lehrstelle bei dem angesehensten Holzschnittzeichner seiner Zeit, Utagawa Toyokuni I., wurde von diesem jedoch abgewiesen. Auf Vermittlung eines begüterten Besitzers einer Leihbibliothek konnte er schließlich im Jahr 1810 oder 1811 bei dem weniger bekannten Utagawa Toyohiro seine Ausbildung beginnen. Von diesem erhielt er, wie durch einen überlieferten Brief bewiesen ist, bereits im Jahr 1812 die Erlaubnis, den Schulnamen Utagawa und den Künstlernamen Hiroshige zu führen. Ungewöhnlich war, dass er bereits vor dem Abschluss der Lehre diese Erlaubnis erhalten hatte. Dass dieser Umstand seiner außergewöhnlichen Begabung geschuldet war, wie häufig in der Literatur behauptet, ist dagegen höchst unwahrscheinlich. Aus dieser Zeit gibt es keine von Hiroshige signierten Arbeiten (ein angeblich von seinem Pinsel stammender Druck aus 1813 ist nach Forrer auf 1819 zu datieren) und auch die Arbeiten, die nach Abschluss der Lehre im Jahr 1818 und den zehn darauf folgenden Jahren von ihm signiert sind, lassen keine überdurchschnittlichen Fähigkeiten erkennen, eher ist das Gegenteil der Fall.

Während der Lehrzeit war der angehende Grafiker wie alle anderen Lehrlinge mit dem Erlernen der Grundtechniken des Malens und Zeichnens einschließlich des Uki-e, dem Nachzeichnen der Arbeiten des Lehrers und anderer angesehener Holzschnittmeister, mit dem Studium anderer Malschulen wie der Nanga- und der Shijō-Schule und von Zeit zu Zeit mit Entwürfen für Buchillustrationen beschäftigt. Toyohiro selbst zeichnete wie andere Künstler des Ukiyo-e Entwürfe für Schauspieler- und Kabuki-Drucke (Yakusha-e), Bilder schöner Frauen (Bijin-ga), Drucke historischer Begebenheiten (Musha-e), Stadtansichten von Edo (Meisho-e) und Illustrationen für die beim Publikum beliebten Ehon.

Bis um das Jahr 1827 herum erhielt Hiroshige von den Verlegern nur wenige Aufträge für Druckentwürfe. Es entstanden einige Buchillustrationen, Kabuki-Drucke, Bijin-ga und Musha-e, die alle besonders von seinem Zeitgenossen Kunisada inspiriert sind, gelegentlich finden sich auch Anklänge an Kuniyoshi. Die Qualität seiner Vorbilder erreichte er jedoch nicht und M. Forrer bezeichnet diese frühen Drucke eher als Kuriositäten.

Im Jahr 1823 hatte Tokutarō/Hiroshige sein Amt als Feuerwehroffizier an seinen Adoptivsohn Nakajirō weitergegeben, für den er noch einige Jahre als Stellvertreter tätig war.[9][10] 1828 verstarb sein Lehrmeister Toyohiro, der ihm vor seinem Tod angeboten hatte, sein Studio und seinen Namen zu übernehmen. Hiroshige hätte dies jedoch aus unbekannten Gründen abgelehnt. Von 1827 an bis ins Jahr 1830 sind von Hiroshige keine Arbeiten bekannt, erst danach erhielt er wieder kleine Aufträge für die Gestaltung von Surimono und entwarf wohl seine ersten „Vogel und Blumen“-Drucke. Gegen 1831 erschien seine erste, 21 Blätter umfassende Serie „Berühmte Ansichten der Osthauptstadt“. Diese in bisher unbekannter Art ausgeführten Drucke haben offensichtlich Anklang beim Publikum gefunden, sie sind bereits in mehreren Auflagen gedruckt worden. Daraufhin erhielt Hiroshige seinen ersten, wirklich bedeutenden Auftrag: Er sollte die Entwürfe für eine 55 Drucke umfassenden Serie der Stationen der Tōkai-Straße zeichnen. Im Folgejahr erschienen die ersten Drucke der Serie „Die 53 Stationen des Tōkaidō“. Spätestens 1834 bzw. 1836 waren alle Drucke der Serie fertiggestellt und wurden als komplette Sammelalben mit Titelblatt und Inhaltsverzeichnis verkauft, ein besonderes Indiz dafür, dass sie bei den Käufern auf rege Nachfrage getroffen waren. Mit den Drucken dieser Serie, unter denen sich einige der bekanntesten Arbeiten Hiroshiges finden, begründete er seinen Ruf als der Zeichner von Landschaften für Farbholzschnitte in den letzten drei Jahrzehnten der Edo-Zeit. In den Jahren bis zu seinem Tod im Jahr 1858 erhielt er zahlreiche Aufträge für die Gestaltung von Farbholzschnitten und Farbholzschnittserien. Die Zahl der von Hiroshige gezeichneten Druckentwürfe wird von manchen Autoren mit ca. 8.000 Arbeiten angegeben, eine realistischere Zahl dürfte wohl 4.000 bis 4.500 sein, plus die zahlreichen Illustrationen für ca. 120 Bücher. Gezeichnet hat er nicht nur die Entwürfe für Landschaftsdrucke, sondern auch für Fächer, Briefumschläge, Bijin-ga, „Vogel und Blumen“-Drucke (Kacho-ga), Spielbretter, und Genji-Drucke.

Trotz dieser enormen Zahl an Arbeiten konnte er mit seinem Handwerk keinen großen Wohlstand erwerben. Für seine Entwürfe bekam er gerade mal doppelt so viel Entlohnung wie die Arbeiter, die an den Befestigungsanlagen von Shinagawa arbeiteten. Zur Verbesserung seiner finanziellen Situation haben die Aufträge für seine Malereien beigetragen, von denen sich einige Dutzend erhalten haben, und für die ihre privaten Auftraggeber für jedes einzelne bis zu einem Jahreseinkommen eines einfachen Arbeiters bezahlt haben.

Ansonsten ist über das Leben Hiroshiges nicht viel bekannt. Eine Autobiografie, die er geschrieben haben soll, ist im Jahr 1876 verbrannt. Eine erste Ehefrau starb 1839. Uspenski erwähnt den Tod eines Sohnes mit dem Namen Tojirō im Jahr 1845. Aus der zweiten Ehe mit Oyasu, der Tochter eines Bauern mit dem Namen Kaemon, hatte er eine Tochter, Otatsu. Diese war in erster Ehe mit Shigenobu verheiratet, dem Adoptivsohn und Meisterschüler Hiroshiges, der nach dem Tod des Lehrers im Jahr 1858 den Namen Hiroshige II. führte. Erst nach dem Tod der ersten Ehefrau war Hiroshige aus den Feuerwehrbaracken ausgezogen, zunächst in das Viertel Oga-chō, dann nach Tokiwa-chō und schließlich um das Jahr 1850 nach Nakabashi Kanō Shindō,[ alle Adressen innerhalb des Stadtgebiets von Edo. Nach dem Jahr 1840 sind mehrere ausgedehnte Reisen in die Provinzen Japans belegt (1841 in die Provinz Kai, 1844 zur Halbinsel Bōsō, 1845 in die Provinz Mutsu und 1848 nach Shinano), auf denen zahlreiche Skizzen der jeweiligen Landschaften entstanden, die später in Druckentwürfe und Gemälde ausgearbeitet wurden.

Im Alter von 62 Jahren starb Hiroshige; beerdigt ist er in einem buddhistischen Tempel im Edo-Stadtteil Asakusa. In den beiden Jahren, die seinem Tod vorausgingen, hat er die Entwürfe für seine letzte Serie „100 berühmte Ansichten von Edo“ gezeichnet. Diese Serie war sein künstlerisches Vermächtnis. Die Drucke zeigen seine Heimatstadt Edo von ihrer schönsten Seite und sie zeigen Hiroshige auf dem Höhepunkt seiner künstlerischen Schaffenskraft. In der Serie sind viele seiner besten Arbeiten enthalten, z. B. der Adler über der schneebedeckten Ebene von Jūmantsubo oder der Regenschauer über der großen Brücke von Atake.

Signaturen

Die meisten Arbeiten Hiroshiges sind mit „Hiroshige ga“ bzw. „Hiroshige hitsu“ bezeichnet, einige Bücher sind mit „Utashige“ (歌重) signiert (1830–44).

Von ihm verwendete Beinamen (gō-Namen) waren Ichiyūsai (von 1818 bis 1830 mit den Kanji „一勇斎“ und 1830/31 mit den Kanji „一幽斎“ geschrieben), Ichiryūsai (一立斎) von 1832 bis 1842 und Ryūsai (立斎) von 1842 bis 1858. Auf Gemälden war gelegentlich zusätzlich zum Namen das Siegel „Tōkaidō“ in Gebrauch.

Schüler

Utagawa Hiroshige II. (1826–69), vormaliger Künstlername Shigenobu; nach dem Tod von Hiroshige I. übernahm er dessen Namen, nach der Scheidung von Hiroshiges Tochter Otatsu im Jahr 1865 nannte er sich wieder Shigenobu (重宣), er gebrauchte ebenfalls den Namen Risshō (立祥).

Utagawa Hiroshige III. (1842–94), vormalige Künstlernamen Shigemasa (重政) und Hiromasa (広政), übernahm den Namen des Lehrers nach seiner Heirat mit Otatsu im Jahr 1865.

Utagawa Hirokage (広景, tätig zwischen 1855 und 1865).

Nakayama Sugakudō (tätig zwischen 1850 und 1860).

Daneben listet F. Schwan noch Shigemasa, Shigemaru, Shigefusa, Shigehisa, Shigeyoshi, Shigehana, Shigetoshi und Shikō (alle ohne weitere Angaben).

Werk

Hiroshiges erste bestätigte Arbeiten wurden 1818 veröffentlicht. Es waren Illustrationen zu dem „Buch der Gedichte Murasakis“ sowie einige Schauspielerdrucke. Im folgenden Jahr entwarf er sein erstes Surimono. Im Jahr 1820 entwarf er einige Serien mit Frauenbildern (Bijin-ga), einige Kriegerbilder (Musha-e) und illustrierte einige Bücher. Bis zum Jahr 1827 folgten vereinzelt ähnliche Drucke, ergänzt um einige Landschaftsserien mit kleinformatigen Drucken und weitere Surimono. Kurz nach 1830 erhielt er vom Verleger Kawaguchiya Shozō den Auftrag für die Gestaltung der ersten Serie mit dem Titel „Berühmte Ansichten der Osthauptstadt“. Eine zweite gleichnamige Serie mit 28 Blättern wurde um 1833/34 von Sanoya Kihei in Auftrag gegeben.

Bereits ein oder zwei Jahre zuvor, um 1832/33, hatte Hiroshige vom Verleger Takenouchi Magohachi (Hōeidō) den Auftrag zum Entwurf von 55 Drucken seiner ersten Tōkaidō-Serie erhalten („Die 53 Stationen des Tōkaidō“, bekannt als Hōeidō Tōkaidō). Mit dieser Serie begründete er seinen Ruf als führendem Künstler des Landschaftsdrucks seiner Zeit.

Viele Drucke der Serie sind inspiriert von Illustrationen bekannter Reiseführer wie dem zuerst von Akisato Ritō im Jahr 1797 kompilierten und in den folgenden Jahren immer wieder neu aufgelegten Tōkaidō meisho zue („Gesammelte Ansichten schöner Plätze entlang der Tōkaidō“). Neu an Hiroshiges künstlerischer Landschaftsauffassung war nicht, dass er „lebendige Straßenszenen mit Menschen aus dem einfachen Volk, die ihren Geschäften auf der großen Straße nachgingen, (zum) Gegenstand der künstlerischen Auseinandersetzung“ machte. Solche Genreszenen waren zuvor bereits unter anderen von Toyohiro und Hokusai gezeichnet worden. Neu an Hiroshiges Bildern war die harmonische Eingliederung der Menschendarstellung in weitläufige Landschaften. Er gestaltete lyrische Bilder, in dem der Betrachter die Stimmung der Natur ungetrübt von philosophischem Nachsinnen über Natur und Mensch unmittelbar wahrnehmen konnte. Hiroshiges Menschen tragen Lasten, aber sie sind nicht belastet. Damit traf er den Geschmack breiter Bevölkerungsschichten und setzte den Gedanken des Ukiyo als der „heiteren, vergänglichen Welt“ vollendet in den japanischen Landschaftsdruck um. Schätzungen zufolge wurden von einzelnen Blättern der Serie bis zu 20.000 Exemplare von den ersten Druckplatten gefertigt, bis diese nicht mehr zu gebrauchen waren. Bereits im 19. Jahrhundert waren neue Platten geschnitten worden, um weitere Auflagen anzufertigen. Im 20. Jahrhundert erfolgten weitere Neuauflagen und selbst im 3. Jahrtausend werden noch immer Drucke dieser Serie als Farbholzschnitte verkauft.

Um 1835 entstand ebenfalls im Auftrag von Takenouchi Magohachi die Serie „Acht Ansichten von Ōmi“ (bekannt als „Acht Ansichten des Biwa-Sees“), die unzweifelhaft zu seinen Meisterwerken gehört. In der ersten Auflage nur in Grautönen gedruckt, zeigen die Drucke der Serie stimmungsvoll die großartige Landschaft rund um einen der beliebtesten Seen Japans. Um dem Publikumsgeschmack entgegenzukommen, mussten für spätere Auflagen allerdings einige Farbplatten hinzugefügt werden. 1836/37 begann Hiroshige Drucke für die Serie „Die 69 Stationen der Kisokaidō“ zu zeichnen. Dieses Projekt hatte der Verleger Iseya Rihei von Magohachi übernommen, der zunächst Keisai Eisen mit dem Entwurf der Drucke beauftragt hatte und der bis 1836 24 Entwürfe geliefert hatte. Die letzten Entwürfe für diese sehr umfangreiche Serie stellte Hiroshige erst im Jahr 1841 fertig.

Von 1835 bis Mitte der 1850er Jahre entstanden einige tausend Meisho-e-Drucke („Bilder schöner Plätze“), die zumeist die Stationen der Tokaidō und die Ausflugsplätze in und um Edo herum zeigen, aber auch Ansichten von Ōsaka und Kyōto waren darunter. Letztlich Variationen ein und desselben Themas, vielfach von fraglichem künstlerischem Wert: Oberflächlich gezeichnet und meist von schlechter Druckqualität, um sie billig als Andenken an Reisende und Ausflügler verkaufen zu können. In den 1840er Jahren beteiligte sich Hiroshige mit einigen Entwürfen an den zusammen mit Kunisada und Kuniyoshi produzierten Serien der „Hundert Dichter“ und der „Parallelbilder zur Tōkaidō“. Und in den 1850er Jahren entstanden mehrere Serien in Kooperation mit Kunisada. Unter anderem die 50 Drucke der Serie „Berühmte Restaurants der Osthauptstadt“ (1852) und die 55 Drucke der Serie „Die Tōkai-Straße von zwei Pinseln (gemalt)“ (1857). Für alle gemeinsamen Serien zeichnete Kunisada die Figuren des Vordergrunds und Hiroshige den Hintergrund bzw. die Kartuschen der Hintergrundbilder. Ein besonders gelungenes Beispiel dieser Zusammenarbeit waren die Triptychen der 1853 entstandenen Serie „Ein moderner Genji“, von der acht Entwürfe bekannt sind.

Hiroshiges Meisterschaft in der Gestaltung des Landschaftsdrucks erreichte in den 1850er Jahren trotz der gleichzeitig produzierten Massenware einen erneuten Höhepunkt.

Serie „36 Ansichten des Berges Fuji“

Beeindruckende Bilder der großartigen Landschaft Japans entstanden in hochformatigen Drucken von bester Druckqualität: 1853–56 in der Serie „Berühmte Plätze der mehr als 60 Provinzen Japans“, 1855 in der Serie „Die 53 Stationen des Tōkaidō“ (die er hier zum letzten Mal alleine zeichnete) und 1858 in den „Die 36 Ansichten des Berges Fuji“ (der tatsächlich letzten von Hiroshige gezeichneten Serie). Uoya Eikichi produzierte schließlich die ebenfalls hochformatige Serie „Hundert berühmte Ansichten von Edo“. Insgesamt erschienen in den Jahren 1856–58 abweichend vom Titel insgesamt 118 Blätter, drei davon von seinem Meisterschüler Shigenobu (Hiroshige II.) gezeichnet (nach dem Tod Hiroshiges I. zeichnete Hiroshige II. im Jahr 1859 den Entwurf eines weiteren Drucks, der in späteren Auflagen das Blatt „Paulownien in Akasaka“ ersetzte). Hiroshige selbst bezeichnete die Drucke dieser Serie als seine beste Arbeit, die sein künstlerisches Vermächtnis darstellen sollte.

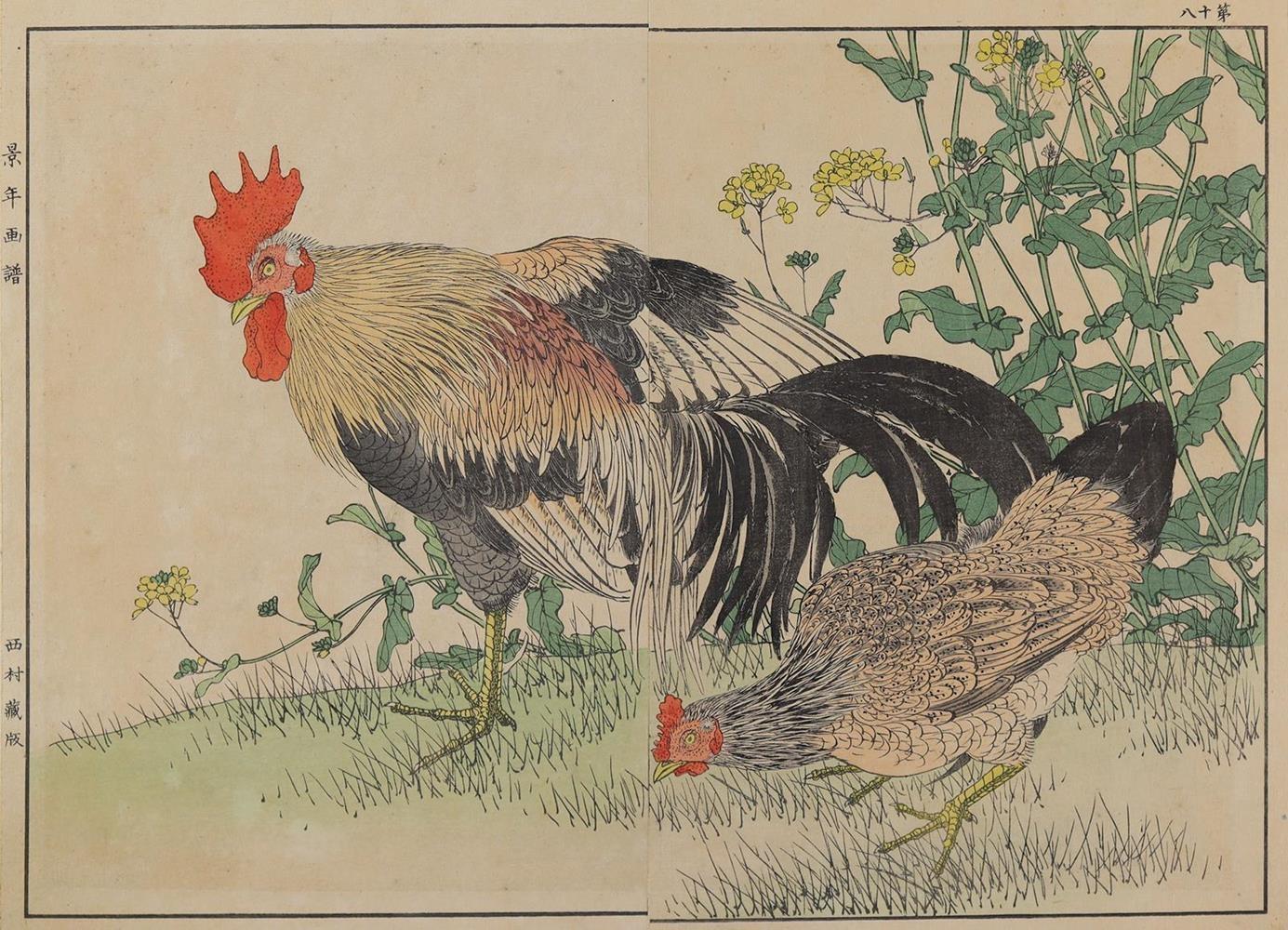

Im Laufe seiner Karriere hat Hiroshige Entwürfe für das gesamte Spektrum des japanischen Holzschnitts gezeichnet. Wenig überzeugend sind dabei seine wenigen Schauspiel-, Krieger- und Chūshingura-Drucke. Beeindruckender dagegen sind seine zahlreichen „Vogel und Blumen“-Drucke, die stimmungsvoll Natureindrücke wiedergeben. Auch unter seinen rund 500 Entwürfen für Fächerdrucke und gelegentlich angefertigten Bijin-ga finden sich ansprechende Drucke. Von Sammlern und Museen geschätzt und gesucht sind ebenfalls einige hundert Gemälde, die er auf Bestellung für seine zeitgenössischen Bewunderer gemalt hatte.

Einfluss

Der Einfluss japanischer Holzschnitte und speziell Hiroshiges Einfluss auf die Malerei des Impressionismus wird besonders an zwei Bildern Vincent van Goghs deutlich, die 1887 in Paris entstanden sind. Die Vorbilder dafür waren zwei Drucke aus der Serie „Hundert berühmte Ansichten von Edo“, „Garten der Pflaumenbäume in Kameido“ und „Regenschauer über der großen Brücke in Atake“ (die Drucke sind Bestandteil von van Goghs erhaltener, knapp 500 Drucke umfassender Sammlung japanischer Holzschnitte, die insgesamt ca. 75 Hiroshige-Drucke beinhaltet). Beide Gemälde van Goghs waren noch vom Pariser Japonismus beeinflusst, sein eigener Stil war noch unentwickelt und die Linienführung schwach. Die kräftigen, flächigen Farbkontraste lassen aber bereits seine weitere Entwicklung erahnen. Wenig später setzte er die wesentlichen Elemente des japanischen Farbholzschnitts (klare Linienführung, stilisierte Formen und farbig gefüllte Flächen) konsequent in die Technik der westlichen Ölmalerei um. Weitere kongeniale Künstler wie Paul Gauguin und Henri Toulouse-Lautrec griffen diese neue Malweise auf.

Kakegawa (vertical from 1855), 1855, Die 53 Stationen des Tōkaidō

Farbholzschnitt auf Japan

Unsigniert, Verleger Tsutaya Kichizo, Zensur: Avatame

35,7 x 24,2 cm,

Auflage Unbekannt

Sehr selten, Zustand ausgezeichnet

Die Station Kakegawa liegt inmitten der seichten Stromschnellen an der Akiba-Straße. Hier sehen wir Reisende, die auf dem Weg in die Stadt vorsichtig durch das Wasser am Bahnhof navigieren.

Hiroshiges Werke aus seiner vertikal ausgerichteten Serie „Die 53 Stationen der Tokaido-Straße“ enthalten einige der bekanntesten Entwürfe des Künstlers. Diese 1855 fertiggestellte Werkserie ist der Höhepunkt der lebenslangen Verbundenheit des Künstlers mit den Menschen und der Landschaft, die diese wichtige Reiseroute bewohnen.

Die 53 Stationen des Tōkaidō (jap. 東海道五十三次之内, Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi), bekannt als Die 53 Stationen des Tōkaidō (Hoeidō-Ausgabe bzw. Hoeidō-Edition) (東海道五十三次之内保永堂版, Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi Hoeidō-ban), ist eine Serie von Farbholzschnitten, die in der ersten Hälfte der 1830er Jahre von dem japanischen Künstler Utagawa Hiroshige entworfen wurde. Mit den Entwürfen für diese Serie begründete Hiroshige seinen Ruf als bedeutendster Landschaftskünstler Japans im Bereich des Farbholzschnitts während der letzten Jahrzehnte der Edo-Zeit. Benannt ist die Serie nach dem Serientitel und dem Zusatz Hoeidō, dem registrierten Firmennamen des Verlegers Takenouchi Magohachi, der für die Produktion des größten Teils der Drucke verantwortlich zeichnete.

Die Hoeidō-Ausgabe war die erste Serie Hiroshiges mit dem Titel Die 53 Stationen des Tōkaidō. Bis zum Tod des Künstlers im Jahr 1858 folgten mindestens neun Serien mit demselben Titel und mindestens 13 weitere, die den Tōkaidō und dessen Stationen zum Thema hatten.

Die Serie umfasst 55 Drucke, beziehungsweise, mit den späteren zweiten Versionen von sechs Drucken, insgesamt 61 Blätter. Herausgegeben wurde die Serie zunächst gemeinsam von den beiden Verlegern Tsuruya Kiemon und Takenouchi Magohachi. Nach der Veröffentlichung von elf gemeinsam produzierten Drucken und einem nur unter seinem Namen erschienenen Druck schied Tsuruya Kiemon aus unbekannten Gründen als Herausgeber aus und Takenouchi Magohachi führte das Projekt allein weiter. Vor dem Erscheinen der 53 Stationen des Tōkaidō war Hiroshige ein weitgehend unbekannter Farbholzschnittkünstler. Die Beliebtheit der Drucke und der damit verbundene Verkaufserfolg machten ihn hinter Kunisada und Kuniyoshi zum beliebtesten Farbholzschnittkünstler seiner Zeit. Die Drucke der Serie erfuhren zahlreiche Neuauflagen und wurden so lange nachgedruckt, bis die ersten Druckplatten verschlissen waren und durch neue ersetzt werden mussten. Bereits in der Meiji-Zeit existierten viele unterschiedliche Versionen von verschiedenen Verlegern. Mit der Entdeckung japanischer Kunst durch westliche Sammler, zunächst aus den USA, dann auch aus Frankreich, Großbritannien und Deutschland, erlangten die Drucke Hiroshiges, und insbesondere die Drucke seiner ersten Serie Die 53 Stationen der Tōkaidō, im Westen Bekanntheit. Die Serie enthält einige der besten Arbeiten des Künstlers, wie zum Beispiel die Stationen Mariko, Kambara, Shōno und Kameyama. Diese Drucke zählen neben Hokusais Großer Welle zu den bekanntesten japanischen Farbholzschnitten außerhalb Japans.

Hokusai und Hiroshige erzielten in ihren Holzschnitten Farbverläufe oder „bokashi“ mithilfe einer sorgfältigen und innovativen Technik, die mehrere Schritte umfasste:

1. **Farbauftrag**: Anstatt die Farbe gleichmäßig auf den Holzschnitt aufzutragen, verwendete der Drucker einen Pinsel, um unterschiedliche Mengen an Farbe aufzutragen und so einen Farbverlauf zu erzeugen. Der Pinsel konnte mit unterschiedlichen Mengen an Farbe und Wasser getränkt werden, was einen allmählichen Farbübergang ermöglichte.

2. **Nasses Papier**: Manchmal wurde das Papier vor dem Druck angefeuchtet. Dadurch konnte die Tinte gleichmäßig verlaufen und weichere Übergänge zwischen den Farben erzeugen.

3. **Mehrere Blöcke**: Hokusai und andere Ukiyo-e-Künstler verwendeten oft mehrere Holzblöcke für einen einzigen Druck, von denen jeder für eine andere Farbe oder Schattierung geschnitzt wurde. Durch sorgfältiges Ausrichten dieser Blöcke konnten sie komplexe Farbverläufe und Schattierungen erzielen.

4. **Handtechniken**: Durch zusätzliche Handtechniken, wie das mehr oder weniger starke Reiben des Papiers in bestimmten Bereichen, konnte auch die Menge der übertragenen Tinte beeinflusst und der Verlaufseffekt verstärkt werden.

5. **Versuch und Irrtum**: Der Prozess erforderte viel Versuch und Irrtum. Drucker fertigten oft mehrere Testdrucke an, um den richtigen Verlauf zu erzielen, bevor sie die endgültige Version produzierten.

Informationen über Hiroshiges und Hokusais Techniken zur Erstellung von Farbverläufen in seinen Drucken, die als „Bokashi“ bekannt sind, finden sich in mehreren maßgeblichen Quellen zum japanischen Holzschnitt und zur Ukiyo-e-Kunst. Zu den wichtigsten Referenzen gehören:

1. **„The Art of Japanese Printmaking“** von Asahi News Service: Dieses Buch bietet detaillierte Einblicke in traditionelle japanische Drucktechniken, einschließlich Bokashi.

2. **„Hokusai: Genius of the Japanese Ukiyo-e“** von Seiji Nagata: Dieses umfassende Werk befasst sich mit Hokusais Leben, seinen Techniken und seinen Beiträgen zur Ukiyo-e, einschließlich seiner innovativen Verwendung von Farbverläufen.

3. **Museumskataloge und Ausstellungsführer**: Institutionen wie das British Museum und das Metropolitan Museum of Art haben umfangreiche Kataloge und Führer zu ihren Ukiyo-e-Sammlungen veröffentlicht, die auch technische Erläuterungen zu Hokusais Werken enthalten.

4. **Wissenschaftliche Zeitschriften**: Artikel in Zeitschriften wie „Impressions“, der Zeitschrift der Ukiyo-e Society of America, befassen sich häufig mit bestimmten Techniken, die von Künstlern wie Hokusai verwendet wurden.

Veröffentlichung

Hiroshige war um 1830 ein weitgehend unbekannter Künstler, der bis dahin nur wenige Aufträge für den Entwurf von Farbholzschnitten erhalten hatte. Um 1830 übertrug ihm der Verleger Kawaguchiya Shōzō den Auftrag, eine Serie von großformatigen Drucken (das heißt Drucke im ōban-Format) von Ansichten bekannter Orte in Edo zu gestalten („Berühmte Ansichten der Osthauptstadt“, Tōto meisho, 東都名所). Die Serie war kein überragender Erfolg, erlebte jedoch bereits mehrere Auflagen, wie unterschiedliche Druckzustände belegen. Die Serie, die Hiroshige als Künstler der Landschaftsdrucke (fūkeiga, 風景画) bekannt machte, war die Serie dem Titel „Die 53 Stationen des Tōkaidō“ (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi).

Zu Beginn der 1830er Jahre erschienen die ersten Drucke dieser Serie und waren ebenso wie die vorhergehende Serie im ōban-Querformat angelegt. Gemeinsame Verleger der ersten elf Drucke waren Tsuruya Kiemon und Takenouchi Magohachi, der Druck der Station Okabe wurde alleine von Tsuruya Kiemon herausgegeben und die weiteren 43 Drucke produzierte Takenouchi Magohachi alleine. Wer die Idee für dieses Projekt hatte und wer wen zuerst angesprochen hat, ist nicht mehr zu klären. Für Takenouchi Magohachi war es das erste Projekt als Verleger, Tsuruya Kiemon war ein alteingesessenes Verlagshaus. Nach Tsuruya Kiemons Ausscheiden, über dessen Gründe nichts bekannt ist, führte Takenouchi Magohachi das Projekt alleine fort.

Titel auf dem Vorsatzblatt, Vorwort und Inhaltsverzeichnis der ersten Gesamtausgabe

Die Drucke zeigen Szenen rund um die Stationen des Tōkaidō, der damals wichtigsten Überlandverbindung von Edo nach Kyōto, und deren umliegende Landschaften sowie zusätzlich den Startpunkt Nihonbashi in Edo und die Endstation bei Kyōto (damals auch Keishi genannt). Sie sind nicht in der Reihenfolge der Stationen entstanden; allenfalls orientierte sich die Reihenfolge der Entwürfe lose an der Abfolge der Raststationen.

Beim Publikum und den zeitgenössischen Kritikern fanden die Drucke großen Anklang und wurden, nachdem alle Einzeldrucke erschienen waren, von Takenouchi Magohachi in zwei Bänden in Buchform herausgegeben. Der Titel auf dem Einband der Bücher lautete „Aufeinanderfolgende Bilder der 53 Stationen des Tōkaidō“ (Shinkei Tōkaidō gojūsan eki tsuzukie, 真景東海道五十三駅続畫). Der Serientitel auf den Drucken selbst blieb unverändert. Allerdings waren die Drucke in den beiden Bänden mittig vertikal gefaltet, da die Bücher im chūban-Format (halbes ōban-Format) erschienen. Viele der heute erhaltenen Drucke der Serie weisen diese Mittelfalte als Hinweis darauf aus, dass sie ursprünglich aus einem dieser Bücher stammen. Heute ist kein vollständiges Exemplar der Erstauflage dieser Bücher mehr bekannt.

Schätzungen zufolge wurden von einzelnen Blättern der Serie bis zu 25.000 Exemplare von den ersten Druckplatten gefertigt, bis diese nicht mehr zu gebrauchen waren. Bereits im 19. Jahrhundert waren neue Platten geschnitten worden, um weitere Auflagen anzufertigen. Im 20. Jahrhundert erfolgten weitere Neuauflagen und selbst im 3. Jahrtausend werden noch immer Drucke dieser Serie als Farbholzschnitte und Reproduktionen verkauft.

Ein größerer Teil der Drucke wurde nach der Erstveröffentlichung einer Überarbeitung unterzogen (Änderung der Farbpalette, Ausfüllen kleiner Fehlstellen, Weglassen einzelner Konturlinien etc.), so dass sie in zahlreichen unterschiedlichen Varianten erhalten sind. Ob diese Veränderungen auf Überlegungen Hiroshiges oder des Verlegers oder gar beider zurückzuführen ist, ist heute nicht mehr feststellbar. Gesichert ist, dass einige der Änderungen bereits nach der ersten Auflage erfolgt sein müssen, da einzelne Blätter im Zustand der Erstauflage extrem selten sind. Von sechs Stationen wurde in der zweiten Hälfte der 1830er Jahre eine zweite Druckversion angefertigt, die möglicherweise verlorengegangene oder beschädigte Druckplatten ersetzten. Diese neuen sind den vorhergehenden Versionen ähnlich, aber nicht mit ihnen identisch.

Der kommerzielle Erfolg der Serie Hiroshiges stand im engen Zusammenhang mit dem immens angewachsenen Reiseverkehr in Japan in den ersten Jahrzehnten des 19. Jahrhunderts, die eine Gesellschaft hervorgebracht hatten, die „süchtig nach Reisen und verrückt nach Souvenirs“ war.

Unmittelbarer Vorgänger von Hiroshiges Serie waren Katsushika Hokusais Drucke der „36 Ansichten des Berges Fuji“, die in ihrem Format und der Bildgestaltung, Darstellung von Menschen, eingebettet in eine sie umgebende Landschaft, Vorbildcharakter sowohl für Hiroshige als auch andere Landschaftsmaler seiner Zeit hatten.

Mit seiner Serie traf Hiroshige jedoch noch mehr als Hokusai den Geschmack breiter Bevölkerungsschichten und setzte den Gedanken des Ukiyo als der „heiteren, vergänglichen Welt“ vollendet in den japanischen Landschaftsdruck um. Neu an Hiroshiges künstlerischer Landschaftsauffassung war nicht, dass er „lebendige Straßenszenen mit geschäftigen Menschen aus dem einfachen Volk (zum) Gegenstand der künstlerischen Auseinandersetzung“ machte. Solche Genreszenen waren zuvor bereits unter anderem von Utagawa Toyohiro und Hokusai gezeichnet worden. Neu an Hiroshiges Bildern war die harmonische Eingliederung der Menschendarstellung in weitläufige Landschaften. Er gestaltete lyrische Bilder, in denen der Betrachter die Stimmung der Natur ungetrübt von philosophischem Nachsinnen über Natur und Mensch unmittelbar wahrnehmen konnte. Die Drucke der Serie waren durchdrungen von expressiver poetischer Sensibilität. Hiroshiges innovativer Stil und die Wahl des horizontalen ōban-Formats stellten einen neuen Schwerpunkt in der Auffassung des Tōkaidō dar und präsentierten eine neue Art des Landschaftsdruckes. Ihre andauernde Popularität und ihr Einfluss auf andere Künstler sind die Gründe für Hiroshiges Ruhm.

Entstehungsgeschichte

Zur Entstehung der Serie hatte Hiroshige III., Schüler Hiroshiges I. und zweiter Ehemann von dessen Tochter, im Jahr 1894 kurz vor seinem Tod beiläufig in einem Zeitungsinterview geäußert, dass die Drucke der Serie auf Entwürfe zurückzuführen seien, die Hiroshige I. als Angehöriger einer offiziellen Delegation des Shōgun angefertigt habe. Die Delegation habe im Jahr 1832 den Auftrag gehabt, ein Pferd als Geschenk des Shōgun Tokugawa Ienari von Edo an den Kaiserhof in Kyōto zu überbringen. Unterwegs habe Hiroshige seine Reiseeindrücke in Skizzen festgehalten und nach seiner Rückkehr nach Edo im 9. Monat des Jahres Tenpō 3 (entspricht in etwa dem September des Jahres 1832) dem Verleger Takenouchi Magohachi angeboten, die Skizzen als Vorlagen für eine Farbholzschnittserie umzuarbeiten. Diese Geschichte übernahm zunächst Iijima Kyōshin in sein 1894 erschienenes Buch „Biografien der Ukiyo-e-Künstler der Utagawa-Schule“ (Utagawa retsuden, 浮世絵師歌川列伝).[23] Dann wurde sie 1930 von Minoru Uchida in dessen erste umfassende Biografie Hiroshiges aufgenommen. Von da an fand sie sich ungeprüft in der gesamten Literatur, die über Hiroshige erschienen ist. Zum Teil wurde sie soweit ausgeschmückt, dass Hiroshige möglicherweise sogar im Auftrag des Shōgun seine Skizzen angefertigt habe.

Suzuki äußerte 1970 in seinem Buch „Hiroshige“ erste Zweifel an dieser Entstehungsgeschichte, indem er auf die Ähnlichkeit der Hiroshige-Drucke der Stationen Ishibe und Kanaya mit den entsprechenden Abbildungen im bereits 1797 erschienenen Tokaidō meisho zue hinwies. Matthi Forrer griff 1997 diese Zweifel auf und wies auf die Unmöglichkeit hin, dass die Serie in 15 Monaten von Oktober 1832 bis zum Ende des Jahres 1834 fertiggestellt worden sein konnte. Weitere Zweifel äußerte Timothy Clark 2004 und bezog sich dabei auf einen 1998 von Jun’ichi Okubo in Japan veröffentlichten Artikel. Clark hält die Geschichte von der Beteiligung Hiroshiges an einer offiziellen Delegation für einen Schwindel. 2004 erschien die bislang umfassendste Monografie über Hiroshiges erste Tōkaidō-Serie von Jūzō Suzuki, Yaeko Kimura und Jun’ichi Okubo, Hiroshige Tōkaidō gojūsantsugi: Hoeidō-ban. Die Autoren wiesen darin nach, dass 26 der 55 Drucke der Serie auf zeitgenössische Vorlagen anderer Künstler zurückzuführen sind. Zudem sei eine Beteiligung von Hiroshige (bzw. Andō als seinem bürgerlichen Namen) an einer shōgunalen Delegation in den erhaltenen Akten nicht verzeichnet. Ebenso wenig ist eine solche Reise im noch zu Lebzeiten Hiroshiges erschienenen Ukiyo-e ruikō („Verschiedene Gedanken über Ukiyo-e“, 浮世絵類考), einer Art zeitgenössischen Who’s who der Farbholzschnittkünstler, erwähnt. Dass die Drucke der Serie nicht auf eigene Skizzen Hiroshiges zurückzuführen seien, sondern auf Vorlagen zeitgenössischer Reiseführer, äußerte Andreas Marks im Zusammenhang mit seinen Beschreibungen der Verlegertätigkeit Takenouchi Magohachis in den Jahren 2008 und 2010. Nachdem Marks für sein Buch Kunisada’s Tōkaidō weitere Bücher nachweisen konnte, aus denen Hiroshige Anregungen für die Gestaltung seiner Drucke entnommen hat, kommt er zu dem Ergebnis, dass die Geschichte von der Entstehung der Drucke als Reiseskizzen nicht länger aufrechtzuerhalten sei.

Datierung

In Übereinstimmung mit der überlieferten Entstehungsgeschichte im Zusammenhang mit der im Dienste des Shōgun unternommenen Reise und der darin dokumentierten Rückkehr Hiroshiges nach Edo im September 1832 wird in der Literatur als Entstehungsjahr der ersten Drucke der Serie das Jahr 1832 angegeben. Das üblicherweise angegebene Datum für die Fertigstellung der Serie spätestens zum Jahresende 1833 folgt aus dem Vorwort des Autors Yomo no Takisui (andere Lesung des Namens: Yomo Ryūsai), das der ersten Gesamtausgabe vorangestellt und mit dem ersten Monat des Jahres Tenpō 5 (in etwa Januar 1834) datiert ist.

Matthi Forrer geht davon aus, dass das Datum der Fertigstellung durch das Vorwort der Gesamtausgabe korrekt angegeben ist, äußert jedoch Zweifel, ob eine Serie von 55 ōban-Drucken innerhalb von nur 15 Monaten zwischen Oktober 1832 und Dezember 1833 hätte fertiggestellt werden können. Keine andere Farbholzschnittserie im ōban-Format hatte in Japan bis dahin einen solchen Umfang gehabt. Der Verleger Takenouchi Magohachi war Sohn eines Pfandleihers und vor der Produktion der Hiroshige-Drucke nicht als Verleger in Erscheinung getreten. Seine finanziellen Ressourcen bzw. seine Kreditwürdigkeit waren nicht ausreichend, das erforderliche Kapital für die Druckplatten, das Papier, die Farben und die Entlohnung für Holzschneider, Drucker und Künstler sowie die Kosten für einen Laden zum Verkauf der Drucke in so kurzer Zeit aufzubringen. Auch wenn zu Beginn der Produktion mit Tsuruya Kiemon ein alteingesessener Verleger beteiligt war, erscheint nach Forrer eine solch kurze Zeitspanne von 15 Monaten außergewöhnlich kurz. Er folgert daraus, dass sich die Fertigstellung der Drucke über einen längeren Zeitraum erstreckt haben müsse und somit die ersten Drucke im Jahr 1831 oder sogar bereits 1830 erschienen sein müssten.

Jūzō Suzuki äußert darüber hinaus Zweifel am Datum der Fertigstellung der Serie zum Jahresende 1833. Ihm zufolge sei im Impressum der Gesamtausgabe als Adresse die Anschrift eines Ladens angegeben, den Takenouchi Magohachi nicht vor dem Neujahrstag 1836 eröffnet habe.

Suzuki ist ebenfalls davon überzeugt, dass Kunisadas bijin-Serie Tōkaidō Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi, bei deren Drucken der Hintergrund in 43 Fällen nach der Vorlage von Hiroshiges Serie gestaltet war, im Jahr 1833 begonnen und im Jahr 1835 vollendet worden war. Die Tatsache, dass 13 der Drucke von Kunisadas Serie einen Hintergrund haben, der von dem der Hiroshige-Drucke abweicht, interpretiert Suzuki so, dass Hiroshige seine Serie im Jahr 1835 noch nicht vollständig entworfen hatte. Kunisadas Verleger, Moriya Jihei und Sanoya Kihei, hätten jedoch darauf gedrängt, die Serie zu vollenden, und daher seien für die letzten, noch fehlenden Drucke Hintergründe aus dem Tokaidō meisho zue und ähnlichen Büchern ausgewählt worden.

Yaeko Kimura war die erste, die wissenschaftliche Nachforschungen zur Biografie Takenouchi Magohachis anstellte und dabei unter anderem die verschiedenen von ihm verwendeten Verlegersiegel verglich. Ihrer Ansicht nach könne eine Gesamtausgabe von Hiroshiges Tōkaidō nicht vor dem Neujahrstag 1836 erfolgt sein.

Da weitere Anhaltspunkte für die exakte Datierung der Drucke der Serie fehlen, kann ihre Entstehungszeit insgesamt nur ungefähr auf die erste Hälfte der 1830er Jahre eingegrenzt werden.

Bildgestaltung

Die Drucke sind im horizontalen (yoko-e) ōban-Format (ca. 39 × 26 cm) ausgeführt. Die bedruckte Fläche ist an allen vier Seiten mit einer dünnen schwarzen Linie von der unbedruckten Papierfläche abgegrenzt. Die Ecken sind nach innen abgerundet, so dass sich zusammen mit den jeweils ca. 1,5 cm breiten Rändern der Eindruck eines gerahmten Bildes ergibt. Bei vielen erhaltenen Drucken sind diese Ränder teilweise oder ganz bis auf den Druckrand beschnitten, wodurch der visuelle Eindruck der Drucke stark verändert wird. Besonders auffällig ist dies bei den Drucken der Stationen Hara und Kakegawa, bei denen ein Bildelement den oberen Rahmen „durchbricht“ und bei denen das durch den Beschnitt verursachte Fehlen dieses Elements die Gesamtkomposition des Druckes zerstört.

Auf allen Drucken sind in irgendeiner Form Reisende auf der Tōkai-Straße dargestellt. Abgebildet sind sie in Verbindung mit Wegen, Flusslandschaften, Bergen, Seen und Meerespanoramen sowie Szenen an oder in Raststationen oder Tempeln. Manchmal sind die Reisenden nur winzig klein in Gruppen als Staffage in der Landschaft zu sehen, manchmal sind sie gestalterisches Element der Drucke und mit individuellen Zügen gezeichnet. Die Drucke folgen keinem Programm, außer dem der Darstellung von Reisenden in unterschiedlichen Szenarien. Die auf den Drucken dargestellten Szenen zeigen keine bestimmte Jahreszeit, stattdessen wechseln sich die jahreszeitlichen Impressionen unsystematisch ab; abgebildet sind Szenen aus allen vier Jahreszeiten, mit Sonne, Regen oder Schneefall. Ebenso unterschiedlich und unsystematisch sind die in den Drucken zu erkennenden Tageszeiten: Zu sehen sind Szenen mit Sonnenauf- und -untergang sowie Szenen, die sich im Tagesverlauf oder im Einzelfall auch nachts abspielen.

An einer freien Stelle innerhalb der Bildkomposition befindet sich der Serientitel „Tōkaido gojūsan tsuki no uchi“. Die kanji des Titels sind in zwei bzw. drei Spalten geschrieben. In jeweils einem Fall ist der Titel in einer Spalte (Station Okabe) bzw. einer Zeile (Station Fuchū) geschrieben. Links vom Serientitel befindet sich leicht abgesetzt der Name der jeweiligen Station und wiederum davon links der Untertitel des jeweiligen Druckes; in einigen wenigen Fällen findet sich der Untertitel direkt unterhalb des Stationsnamens. Serientitel und Stationsnamen sind in Schwarz gedruckt; die Untertitel befinden sich in einer roten Kartusche, die in Negativ- oder Positivdruck ausgeführt ist.

Vom Serientitel abgesetzt, in vielen Fällen auf der gegenüberliegenden Seite des Blattes, ist die Signatur Hiroshiges (Hiroshige ga, 廣重画) in schwarzen kanji gedruckt. Unterhalb der Künstlersignatur findet sich ein rotes Verlegersiegel in unterschiedlichen Formen. Bei der zweiten Version des Druckes der Station Odawara findet sich ein zusätzliches rotes Verlegersiegel rechts oberhalb des Serientitels.

Das Zensursiegel kiwame (極 für ‚geprüft‘) befand sich ursprünglich bei allen Drucken auf dem linken unteren Randbereich der Blätter. Bei den ersten drei Stationen, Nihonbashi, Shinagawa und Kawasaki, sowie der Station Totsuka wurde nach der Überarbeitung der Bildkomposition das ursprüngliche gemeinsame Siegel der Verleger Senkakudō und Hoeidō durch ein kalebassenförmiges Siegel Hoeidōs mit einem integrierten Zensursiegel ersetzt und somit das kiwame-Siegel am linken Rand überflüssig. Auf den zweiten Versionen der Drucke der Stationen Kanagawa und Odawara ist das kiwame-Siegel ebenfalls vom linken Rand entfernt und durch ein Verlegersiegel mit integriertem kiwame-Siegel ersetzt worden.

Utagawa Hiroshige wurde 1797 als Andō Tokutarō (安藤 徳太郎) im Stadtviertel Yayosugashi (heute Marunouchi im Stadtbezirk Chiyoda) in Edo, dem heutigen Tokyo geboren. Seine Rufnamen in späteren Jahren waren Jūemon (重右衛門), Tokubē (徳兵衛) und eine Zeit lang Tetsuzō.

Hiroshige, bijin, Serie „Acht Ansichten - Frauen und Landschaften im Vergleich“, Anfang 1820er

Sein Vater war Mitsuemon Genemon, der von Andō Jūemon adoptiert worden war und von diesem das erbliche Amt eines untergeordneten Feuerwehroffiziers (Hikeshi Dōshin, „Verwalter der Vereinigung zur Feuerbekämpfung“) im Dienst des Bakufu übernommen hatte. Als Dienstmann des Bakufu war er Angehöriger des Samurai-Stands, sein Einsatzgebiet war das Viertel Yayosugashi.

Im Februar 1809 starb Tokutarōs Mutter. Im selben Monat übergab ihm sein Vater das Amt des Feuerwehroffiziers, wenige Monate später, gegen Ende des Jahres, starb auch der Vater. Von seinen drei Schwestern ist nur bekannt, dass die älteste bereits im Jahr 1800 verstorben war.

Tokutarō war Vorgesetzter einer kleinen Gruppe von Feuerwehrleuten. Seine Lebensverhältnisse waren bescheiden. Die mit dem Amt verbundene Besoldung war gerade ausreichend, zwei Menschen ein Jahr lang mit Reis zu versorgen. Die zehn Baracken, in denen die Feuerwehrabteilung untergebracht war, musste er sich mit 30 weiteren Offizieren und 300 Mannschaften und deren Familien teilen. Wie andere Angehörige des untersten Rangs der Samurai, den Gokenin, war er gezwungen, sich nach anderen Einkünften umzusehen. Gokenin-Familien beschäftigten sich oft mit Heimarbeit wie der Herstellung von Schirmen, Kisten und Holzsandalen.

Die Pflichten eines Feuerwehroffiziers in Edo zu Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts waren allem Anschein nach nicht besonders umfangreich und so hatte Tokutarō nebenbei Zeit, eine Lehre als Farbholzschnittzeichner zu beginnen. Weshalb er ausgerechnet diesen handwerklichen, bürgerlichen Beruf wählte, um ein Zubrot zu seinem Lebensunterhalt zu verdienen, ist völlig ungeklärt.

Inoffiziellen Malunterricht im Stil der Kanō-Schule hatte er bei einem seiner Vorgesetzten und Freund, Okajima Rinzō (oder Rinsai), erhalten. Für einen Angehörigen des Samurai-Stands, selbst des niedrigsten Rangs, wäre dies nichts Außergewöhnliches, da Kalligrafie und Grundkenntnisse des Malens zu deren Standardausbildung gehörten. Die Signatur eines angeblich aus seiner Kindheit erhaltenen Gemäldes, das eine Gesandtschaft des Königs der Ryūkyū-Inseln zum Shogun zeigt, und seine frühe außerordentliche zeichnerische Fähigkeit beweisen soll, ist nach Forrer zweifelhaft, und selbst wenn es Hiroshige zugeschrieben werden könnte, ließe es keine besondere Begabung erkennen.

Der Überlieferung nach bewarb sich Tokutarō zunächst um eine Lehrstelle bei dem angesehensten Holzschnittzeichner seiner Zeit, Utagawa Toyokuni I., wurde von diesem jedoch abgewiesen. Auf Vermittlung eines begüterten Besitzers einer Leihbibliothek konnte er schließlich im Jahr 1810 oder 1811 bei dem weniger bekannten Utagawa Toyohiro seine Ausbildung beginnen. Von diesem erhielt er, wie durch einen überlieferten Brief bewiesen ist, bereits im Jahr 1812 die Erlaubnis, den Schulnamen Utagawa und den Künstlernamen Hiroshige zu führen. Ungewöhnlich war, dass er bereits vor dem Abschluss der Lehre diese Erlaubnis erhalten hatte. Dass dieser Umstand seiner außergewöhnlichen Begabung geschuldet war, wie häufig in der Literatur behauptet, ist dagegen höchst unwahrscheinlich. Aus dieser Zeit gibt es keine von Hiroshige signierten Arbeiten (ein angeblich von seinem Pinsel stammender Druck aus 1813 ist nach Forrer auf 1819 zu datieren) und auch die Arbeiten, die nach Abschluss der Lehre im Jahr 1818 und den zehn darauf folgenden Jahren von ihm signiert sind, lassen keine überdurchschnittlichen Fähigkeiten erkennen, eher ist das Gegenteil der Fall.