Your enquiry email was sent successfully.

Your email was sent successfully.

Your enquiry email for favorites was sent successfully.

Max Ackermann and Otto Dix - The Höri as a refuge

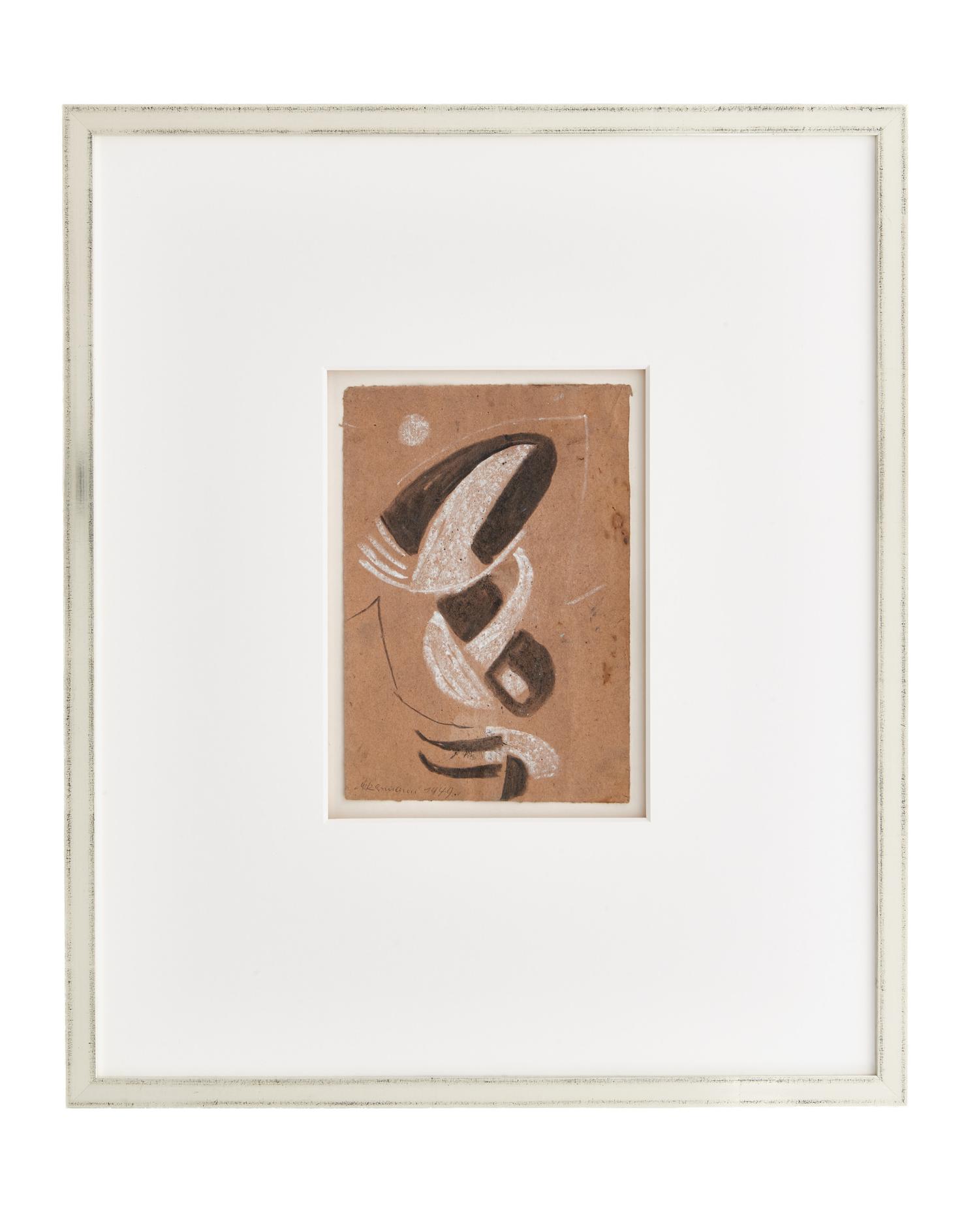

recto

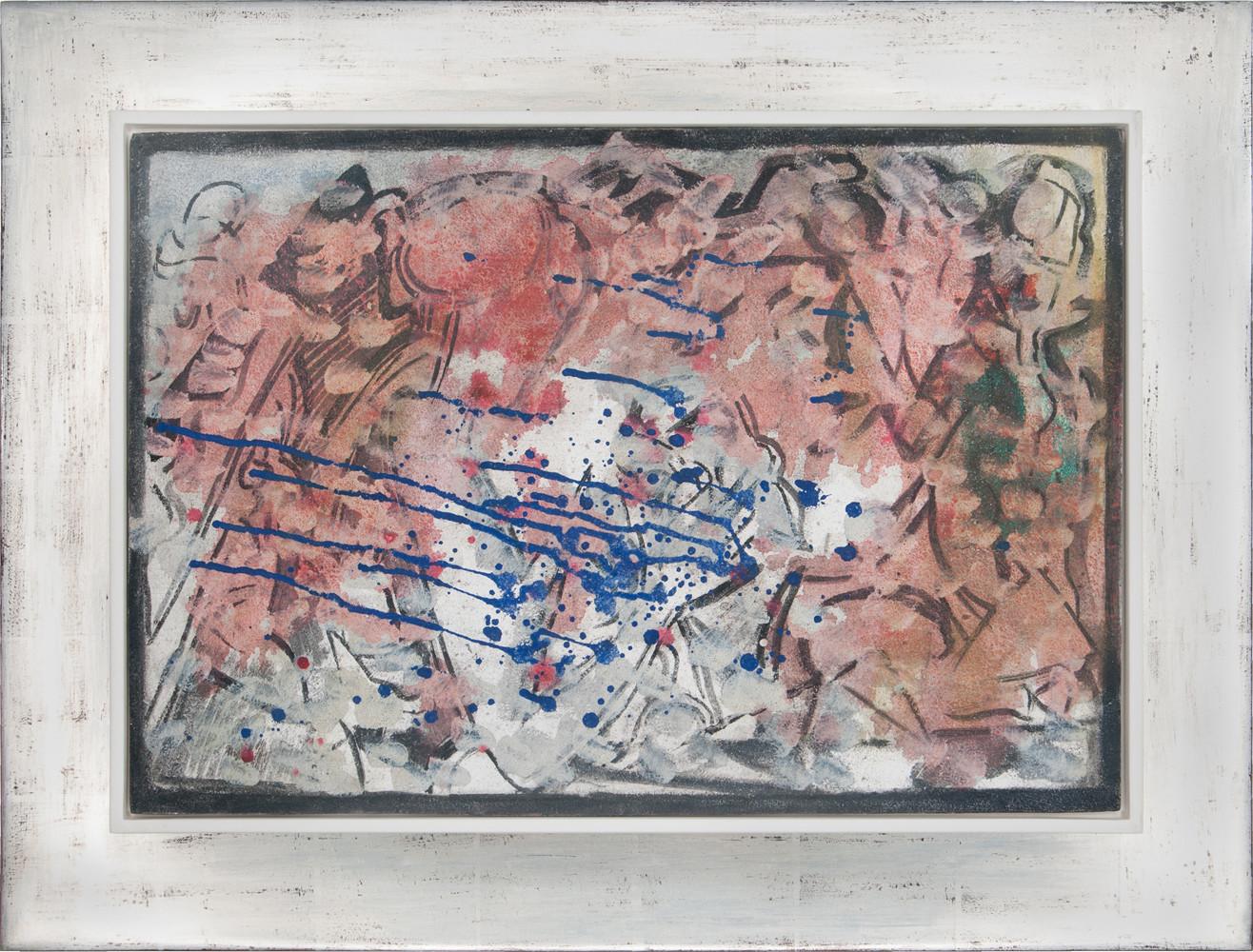

monogrammed and dated by the artist within the picture "M. A.46"

verso

signed and dated by the artist in dark blue chalk

"M. Ackermann

horn

Diagonal 1946 "

framed

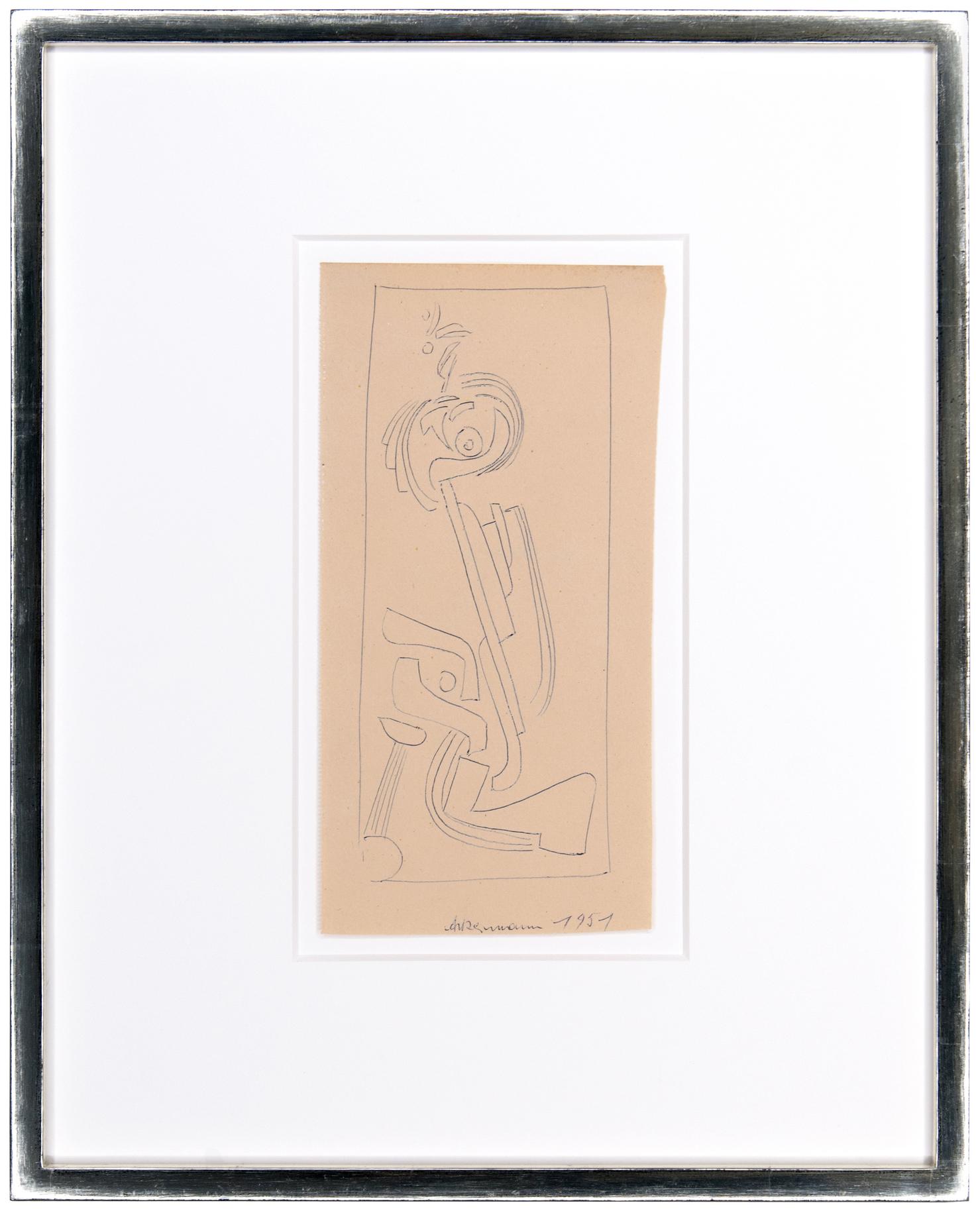

on the bottom right in graphite by the artist's own hand referred to as:

"M.A. 49."

signed and dated by the artist on the lower left with black ballpoint "Ackermann 1949"

verso

unmarked

framed

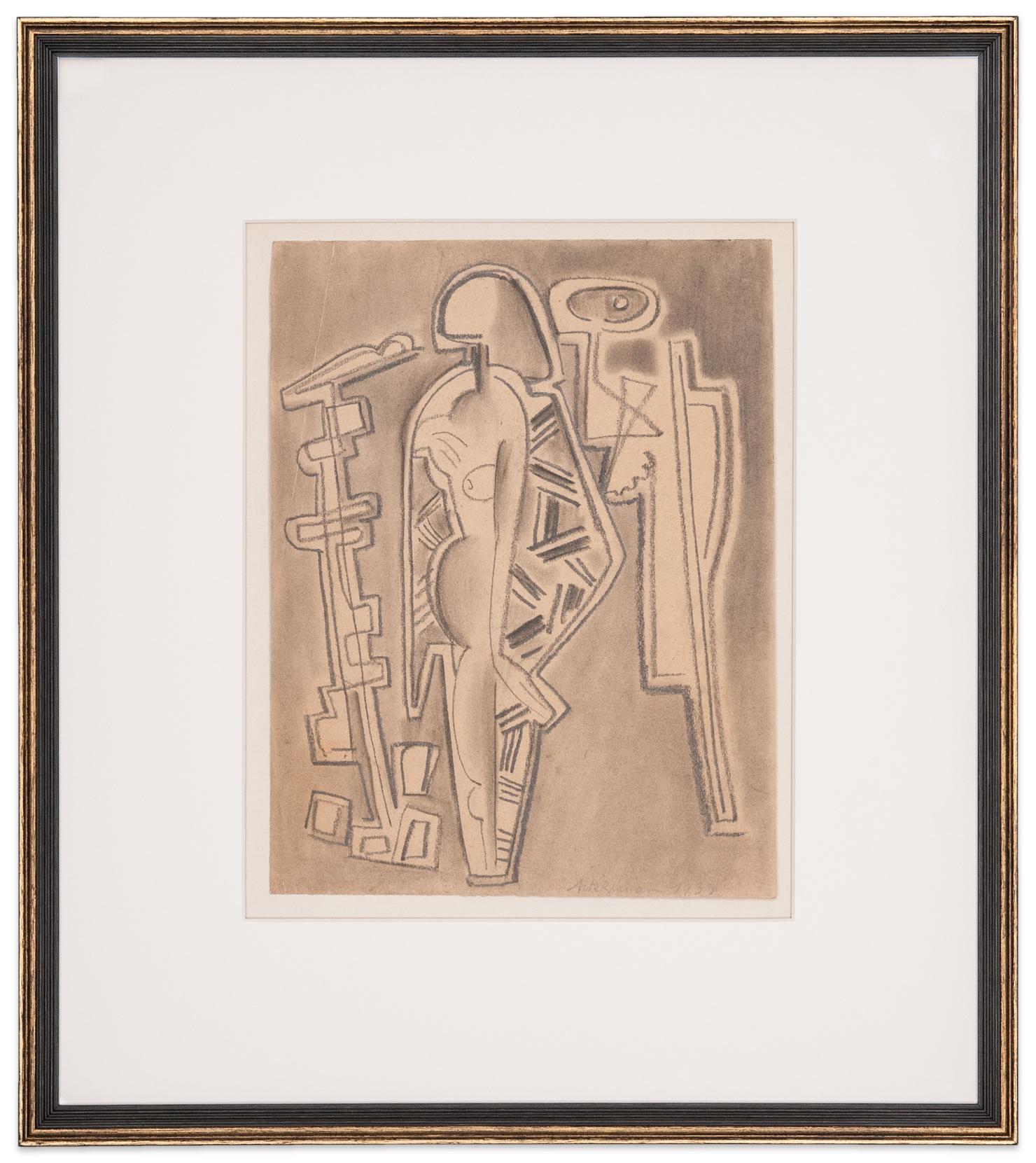

on the bottom right in graphite by the artist's own hand referred to as:

"M.A. 49."

recto

signed and dated in blue ballpoint by the artist on the lower right "Ackermann 1951"

verso

signed and dated by the artist in blue ballpoint "Max Ackermann 1951"

framed

recto

signed and dated in pencil by the artist in the lower center "Ackermann 1953"

verso

unmarked

framed

recto

signed and dated in pencil by the artist on the lower right "Ackermann 53"

verso

unmarked

framed

recto

signed and dated by the artist on the lower right "Ackermann 1955"

verso

unmarked

Paper watermark INGRES (pressed through on the front)

framed

State Gallery Stuttgart

recto

Inscribed by the artist in black chalk on lower left:

"M.A. 36"

verso

inscribed on the canvas in graphite by the artist:

"Ackermann / 1936."

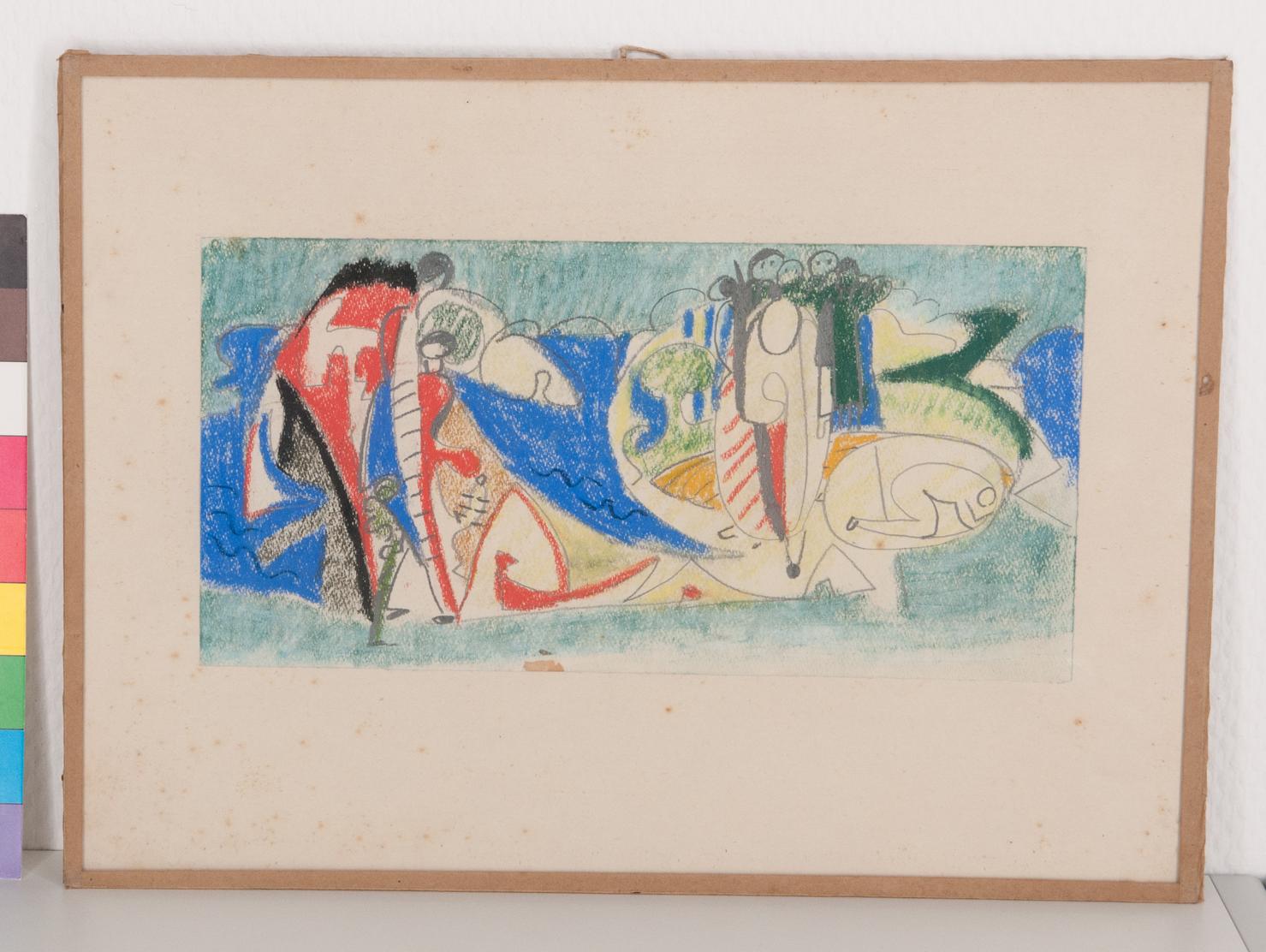

In 1933, with the ban by the National Socialists, he retreated into "inner emigration" to the Höri Peninsula on Lake Constance. This retreat marked a new beginning. His encounter with Gertrud Ostermayer led to a turning point in his life, which culminated in a new creative period. From then on, human beings, nature, and landscapes merged in abstraction, combining the artist's efforts toward realistic depiction and abstract dissolution. The drawings created in Horn can therefore be considered central works in Max Ackermann's oeuvre.

stamp

"Property Gertrud Ackermann

with the inventory

number 30.7052"

ACK number 2376 noted on the

verso

1933, mit dem Verbot durch die Nationalsozialisten, zog er sich zur "Inneren Emigration" auf die Halbinsel Höri am Bodensee zurück. Dieser Rückzug bedeutete gleichzeitig einen Neuanfang. Die Begegnung mit Gertrud Ostermayer führte zu einer Lebenswende, die in eine neue Schaffensperiode mündete. Mensch, Natur und Landschaft verschmolzen von nun an in Abstraktion und führten das Bemühen des Künstlers um realistische Wiedergabe und abstrakte Auflösung zusammen. Die Zeichnungen, die in Horn entstanden, dürfen deshalb als zentrale Arbeiten im Werk von Max Ackermann verstanden werden.

"Max Ackermann, Horn Bodensee, 1933"

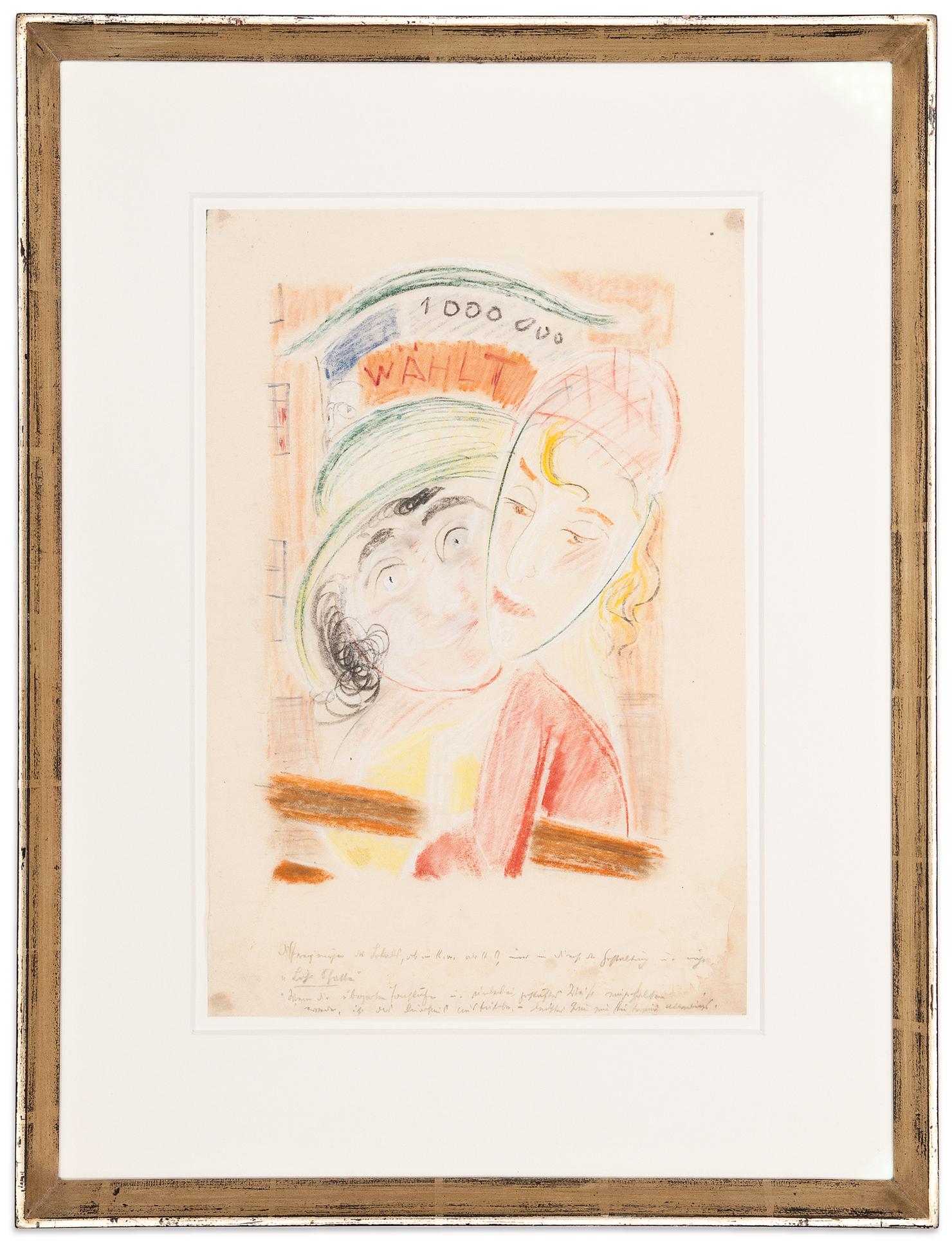

Für Max Ackermann begann Mitte der 1920er Jahre mit seinem beginnenden Interesse für Sport, Spiel und Badestrand ein Umbruch. Abstrakte Themen und deren Umsetzungen gewannen zunehmend an Bedeutung. 1930 gründete er an der Stuttgarter Volkshochschule ein "Seminar für absolute Malerei". Dort unterrichtete er im Sinne und in der Tradition Adolf Hölzels und entwickelte durch theoretische Studien und praktische Übungen die Lehre von den Bildgesetzen.

1933, mit dem Verbot durch die Nationalsozialisten, zog er sich zur "Inneren Emigration" auf die Halbinsel Höri am Bodensee zurück. Dieser Rückzug bedeutete gleichzeitig einen Neuanfang. Die Begegnung mit Gertrud Ostermayer führte zu einer Lebenswende, die in eine neue Schaffensperiode mündete. Mensch, Natur und Landschaft verschmolzen von nun an in Abstraktion und führten das Bemühen des Künstlers um realistische Wiedergabe und abstrakte Auflösung zusammen. Die Zeichnungen, die in Horn entstanden, dürfen deshalb als zentrale Arbeiten im Werk von Max Ackermann verstanden werden.

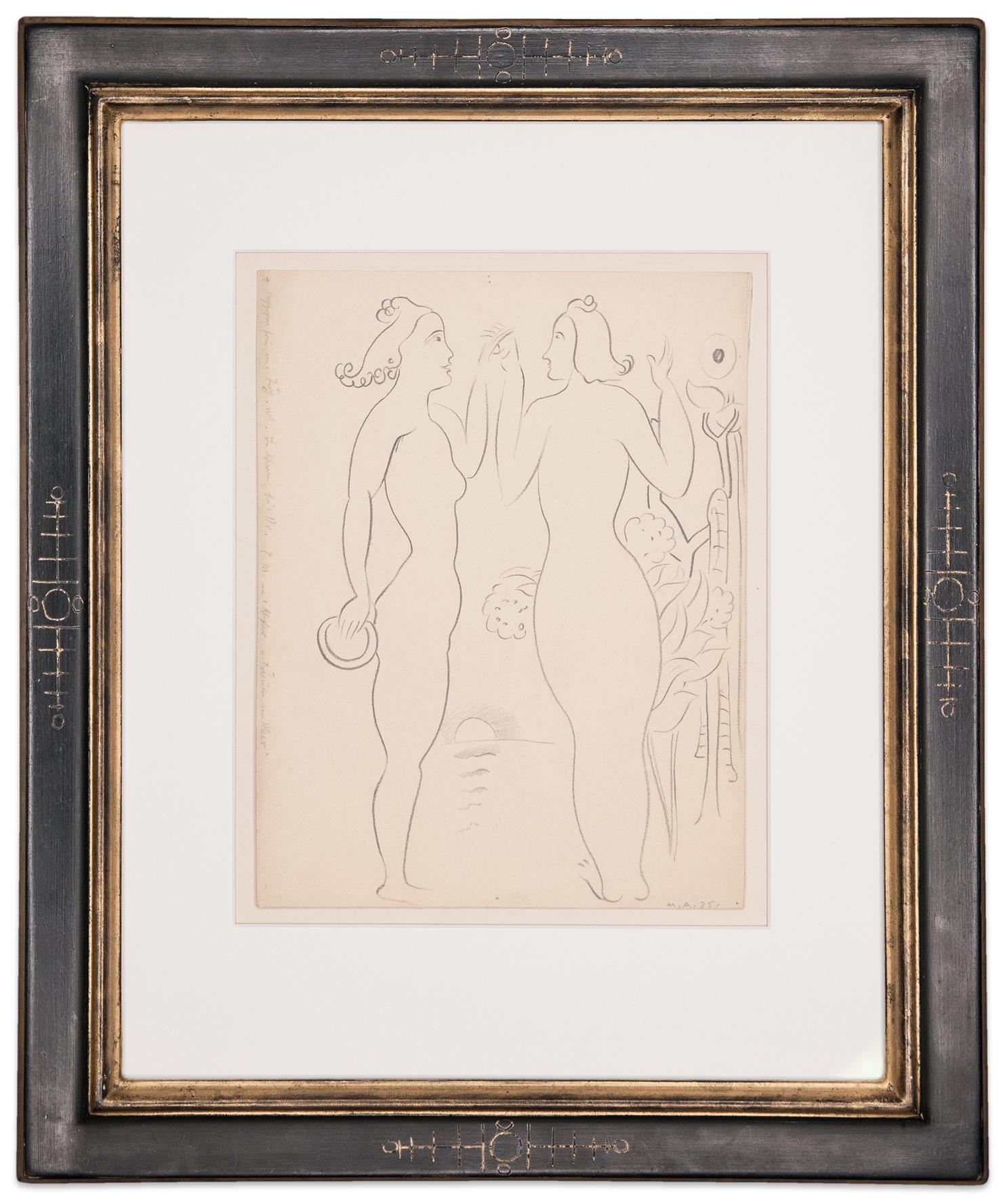

"Max Ackermann, Horn Bodensee, Badende Frauen 1935"

inscribed by the artist on the left side of the recto and

additionally

titled "Women by the sea"

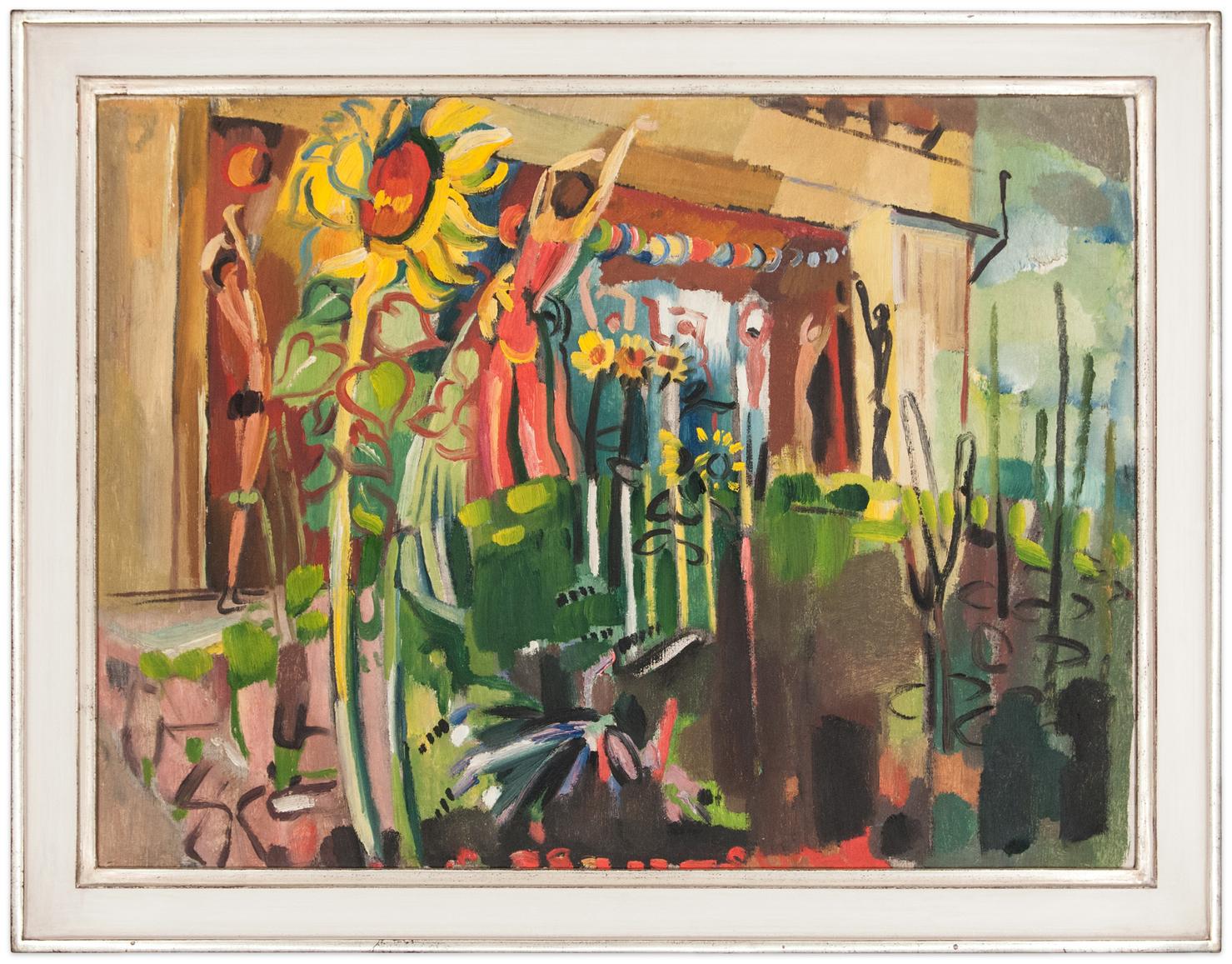

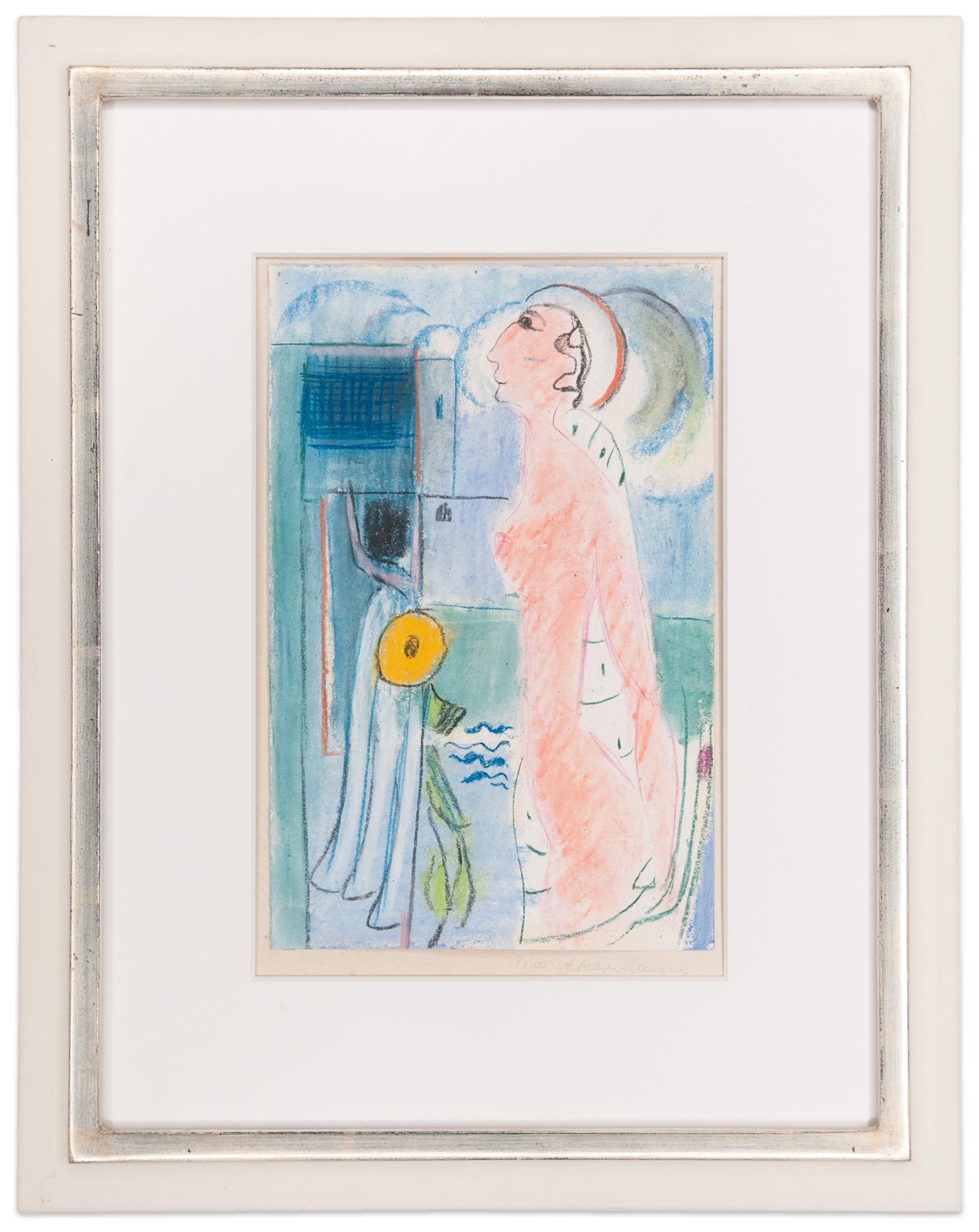

Max Ackermann's painting depicts a view of his home in Horn on Lake Constance, combining landscape, architecture, and figurative representation in a harmonious composition. The scene is imbued with a gentle, almost meditative atmosphere. At the center is a lovingly tended garden, where a profusion of flowers blooms in intense colors. The plants seem to unfold almost rhythmically in space—a reference to Ackermann's preoccupation with dynamic compositional principles.

Several human figures can be seen among the flowers and near the house. They are not individualized in a portrait-like manner, but are depicted in a loose, almost sketch-like style. They reflect Ackermann's view of movement as an essential part of life – and thus also as a central element of his artistic conception.

Max Ackermann, who always sought the connection between spiritual abstraction and sensual experience in his work, understood movement in the great outdoors not only as physical activity, but also as an artistic principle. In his later work, he developed an “art of movement” based on inner rhythms, energetic lines, and color vibrations. In this painting, too, the forms are gently modulated, the lines are organic, and the color fields vibrate in a balanced tension.

The architecture of the house—restrained and nestled in greenery—forms a calming center in the composition, while Lake Constance in the background lends depth and breadth. The lake, slightly shrouded in mist, opens the scene to the horizon and underscores the contemplative dimension of the painting.

"Max Ackermann, Stuttgart, 1933"

Das Pergamin ist auf einen Unterlagekarton montiert

recto

monogrammed and dated by the artist in pencil on the lower left "M.A.46"

verso

signed and dated by the artist in pencil "Max Ackermann Stuttgart 1946"

framed

additionally signed and

additionally signed

and extensively inscribed below the image

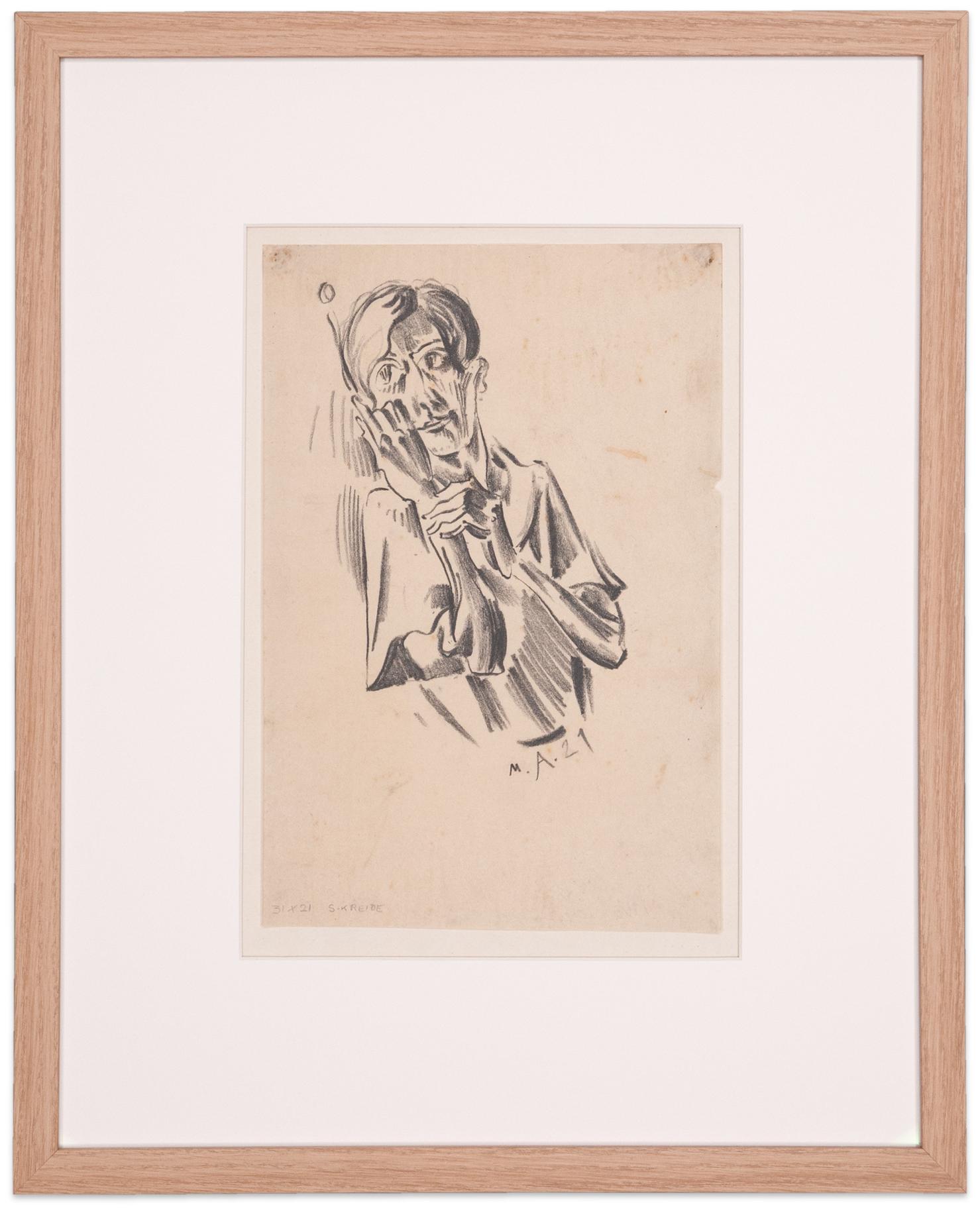

"Max Ackermann, 1921"

recto

unmarked

verso

inscribed by the artist in black tempera in the upper left corner M. ACKERMANN / HORN / STRAND 1940

inscribed by the artist's own hand at the lower right edge of the picture (inverted) in black tempera: P. A.ST. / 55 / 38

unbezeichnet

verso

blauer Stempel: Eigentum Gertrud Ackermann

Das Werk wurde vom Künstler weder signiert, datiert, noch bezeichnet. Es

handelt sich um eine abstrakte Komposition, die aus dem Thema "Strand

und Figuren" abgeleitet werden kann. Ackermann variierte dieses Thema

während seiner Bodenseezeit häufig. In den 40er Jahren abstrahierte er es

stärker als in den 30er Jahren, weshalb das Gemälde ACK2326 in die 40er

Jahre zu datieren ist.

"Max Ackermann, Horn, 1937"

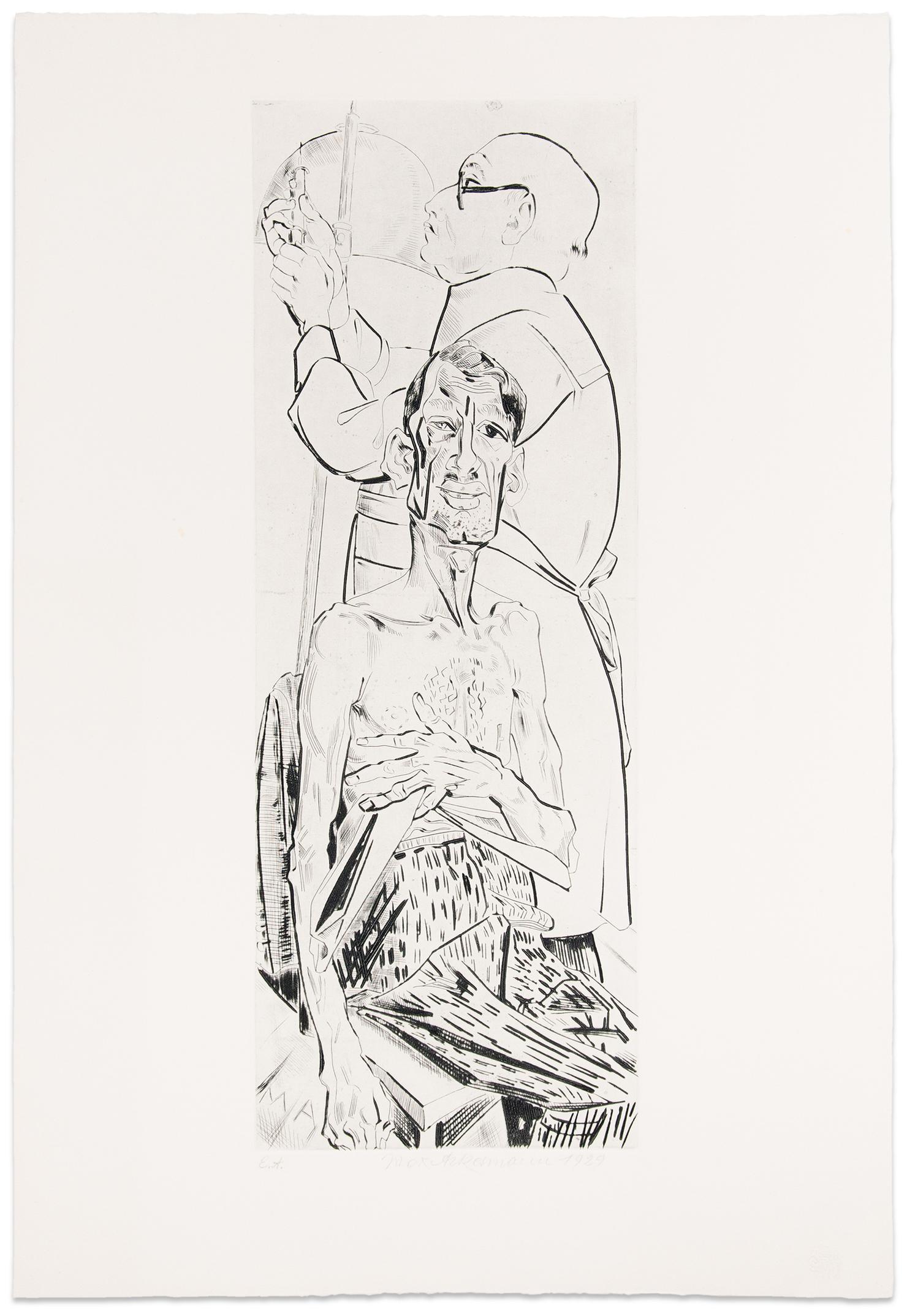

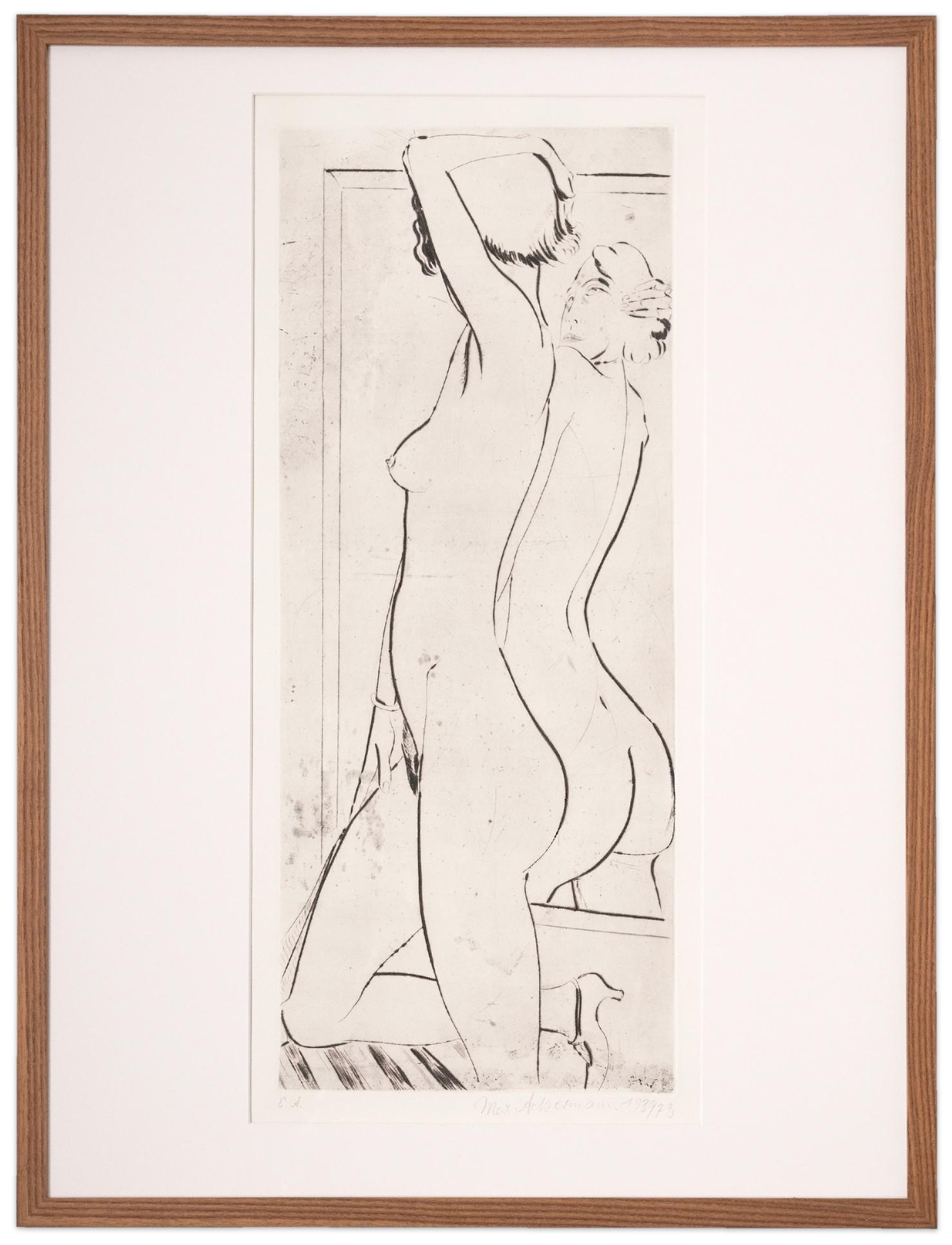

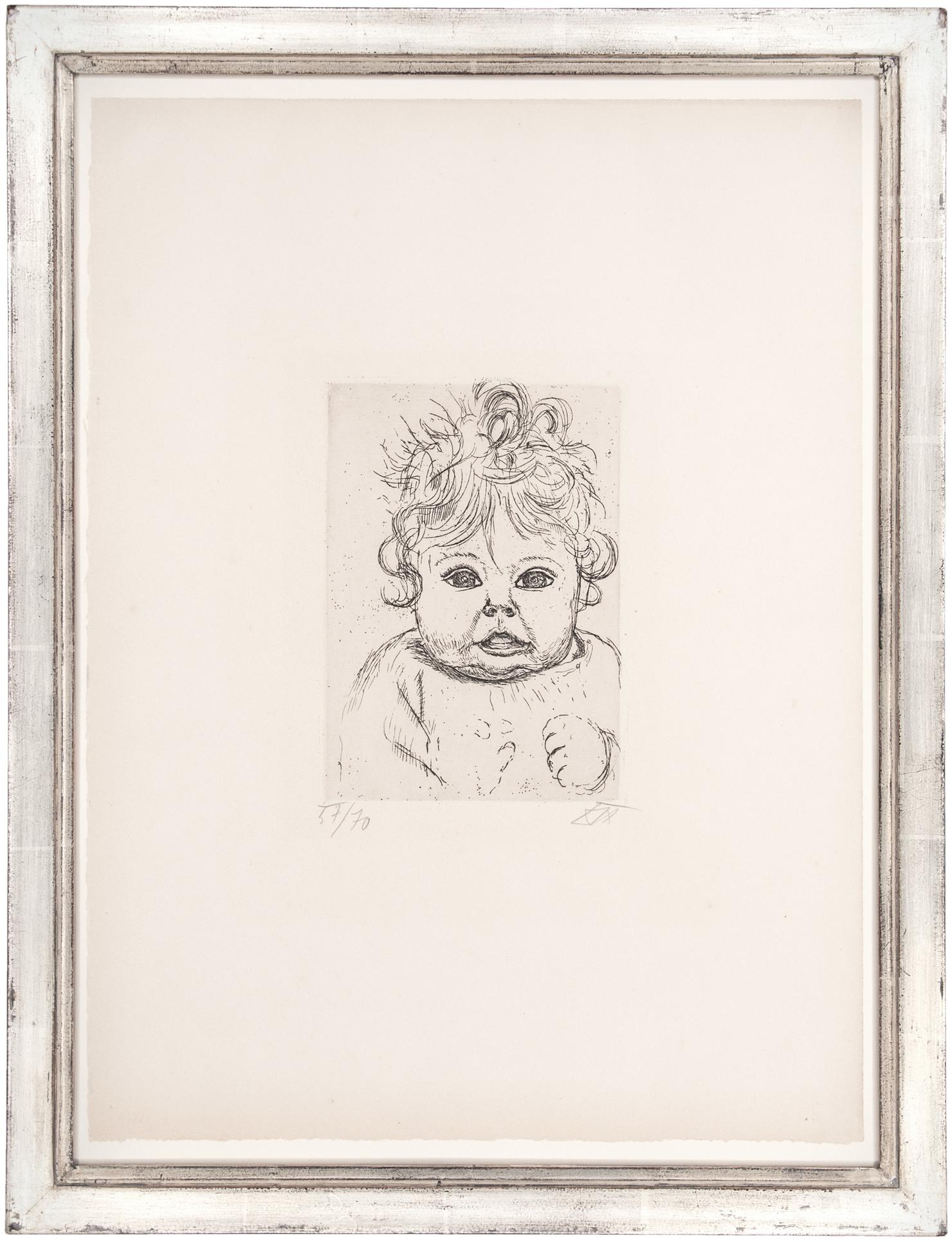

The work epitomises the transition from traditional nude depictions to a more modern, psychological approach. Ackermann dispenses with idealised forms and instead concentrates on human physicality and the intimate situation of looking at oneself.

The print "Before the Mirror" is not only a study of the human body, but also an exploration of the self-perception and inner life of the sitter, which became increasingly important in art in the 1920s.

Further printing from original printing plates that survived the destruction of the studio in the 2nd World War.

survived. These are dated 1923 (creation of the printing plate)/1973 (reprint).

Completely framed with passepartout.

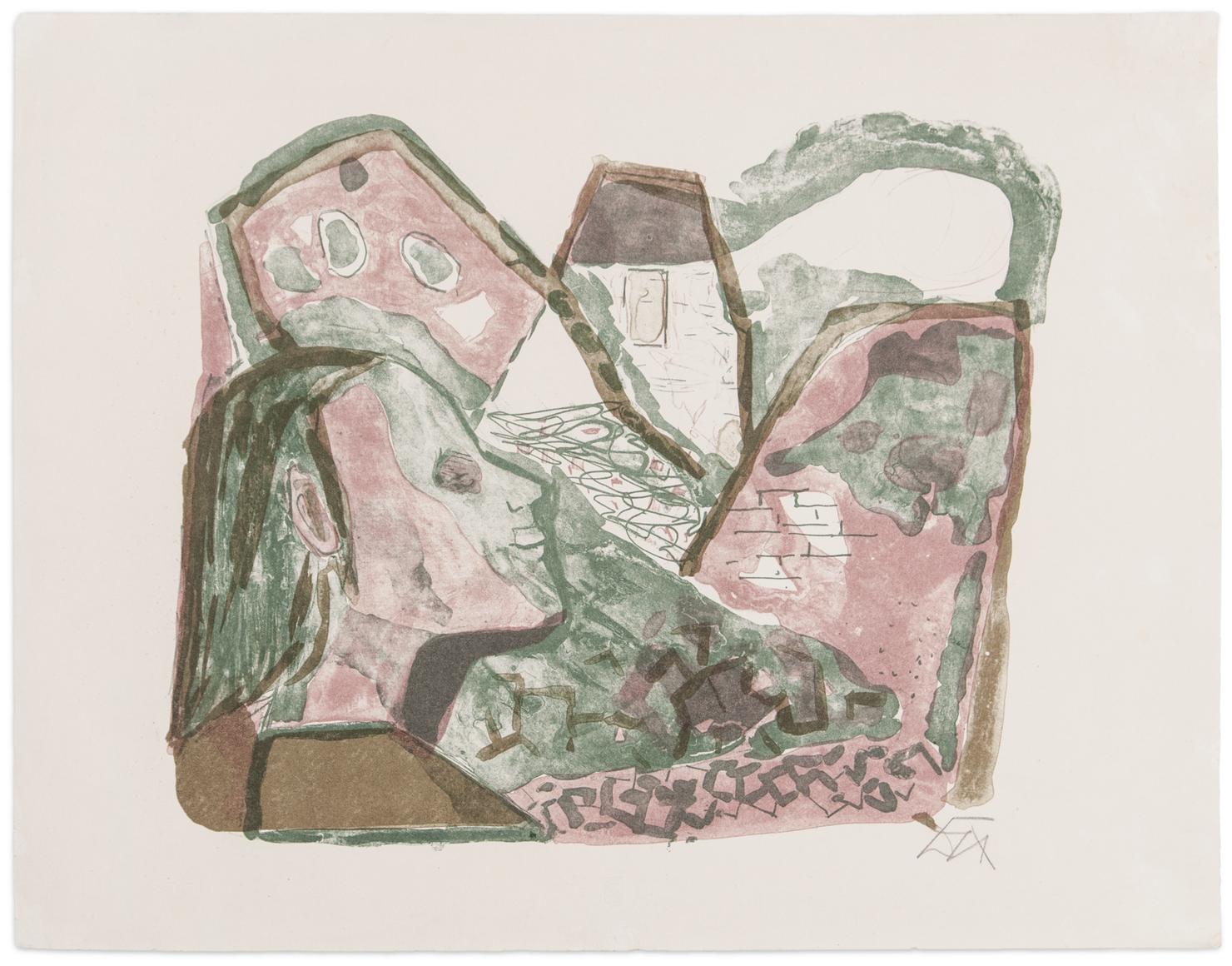

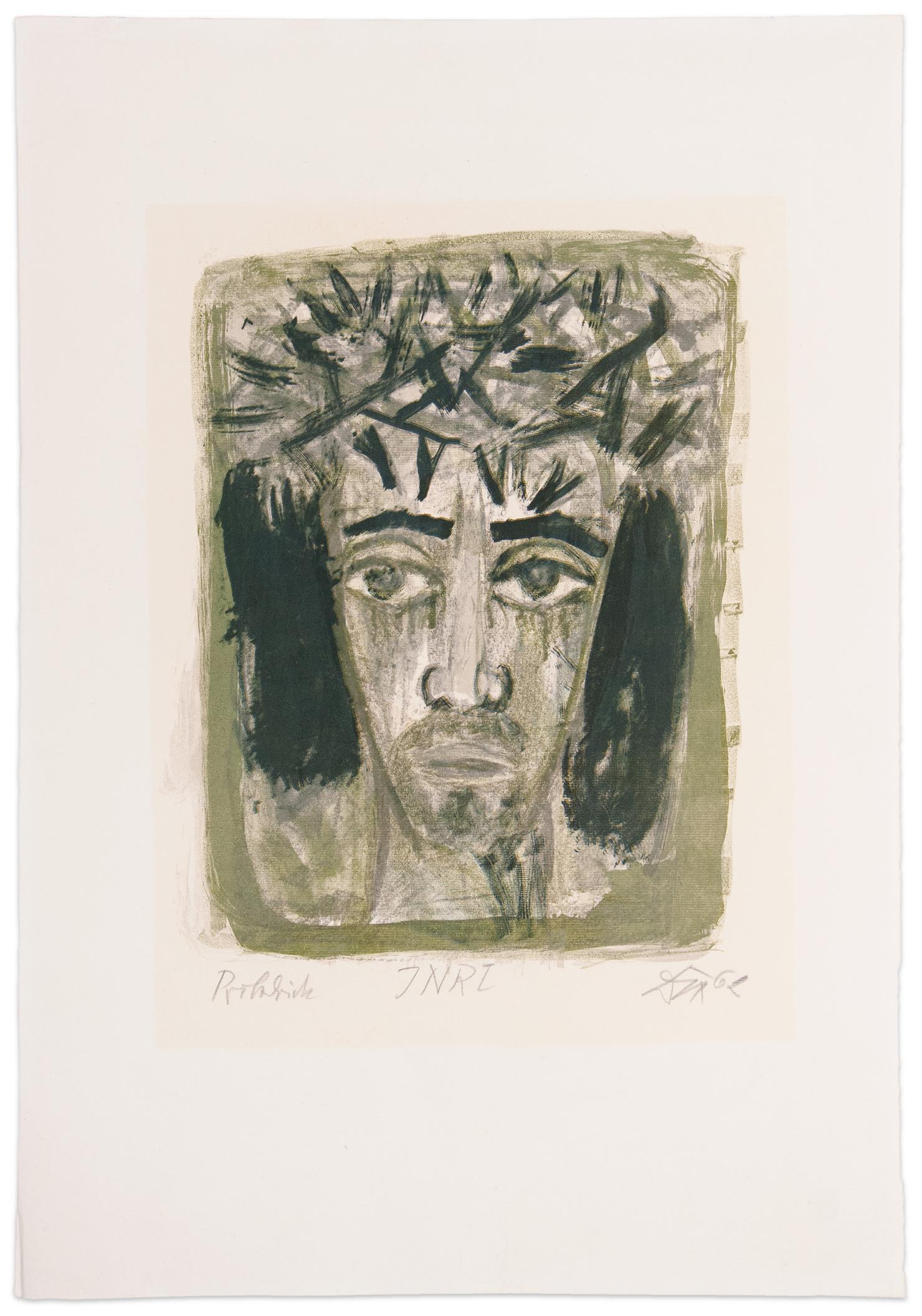

(The Graphic Work) p. 141, Lithographic chalk and litho ink

inscribed and titled in the lower margin

WV Lorenz IE. 7.16.22

1. Zeichnungsstein: Graugrün 2. Konturstein: Rotbraun 3. Flächenstein: Hellviolett

Dresden Akademiedruck

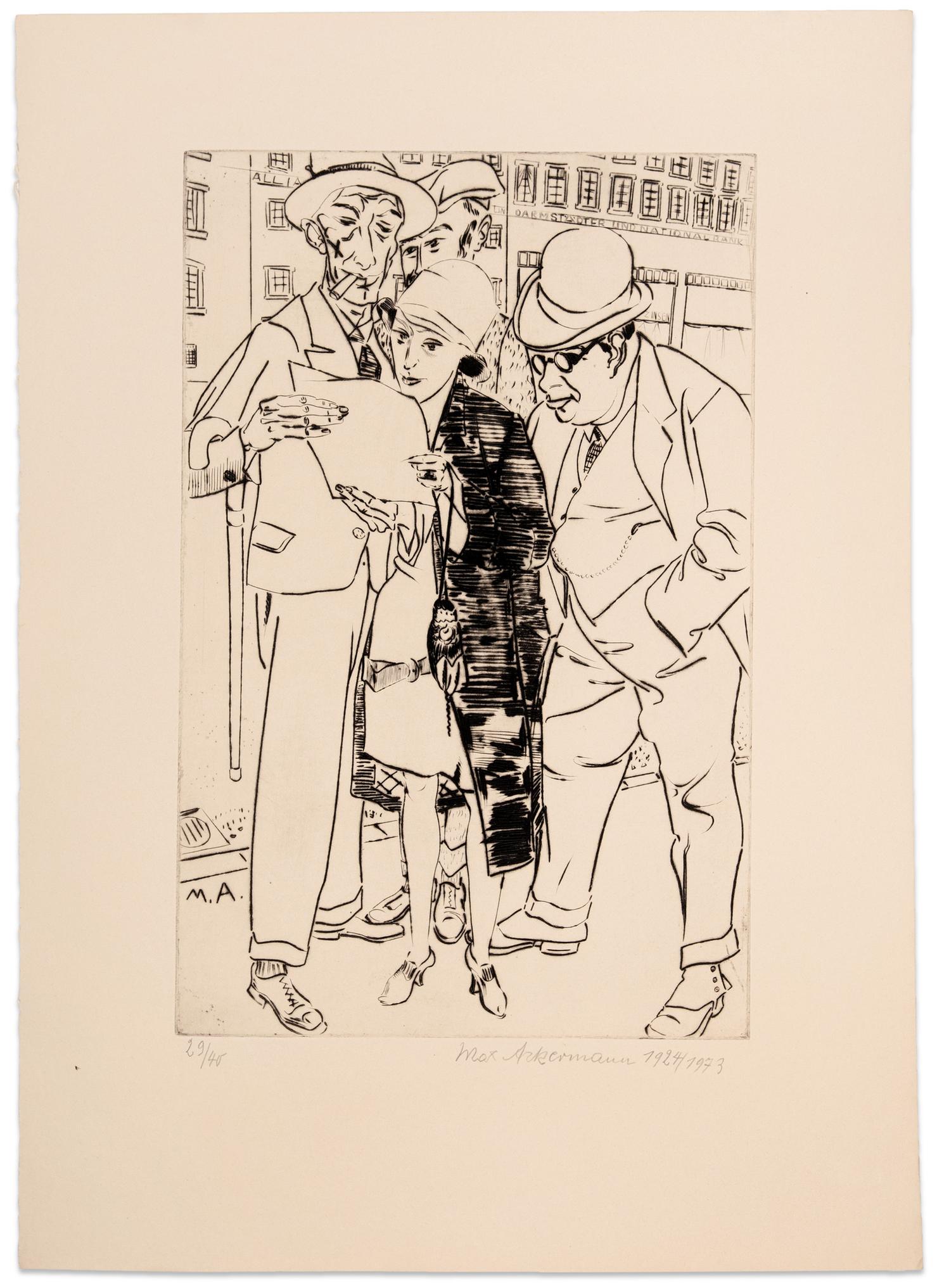

In: "Otto Dix: Das graphische Werk" Abb. 184

Blindstempel: Akademie der bildenden Künste DresdenAkademiedruck

Bemerkung: Es gibt Exemplare, die auf 10 nummeriert sind

Drucker: Ehrhardt

Verleger: Otto Dix

verschiedene Farbvariationen

Verleger: Karl Nierendorf

In: "Otto Dix - Das graphische Werk" S. 112

Verleger Karl Nierendorf

in the catalog raisonné incorrectly mentions

of 30 copies

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

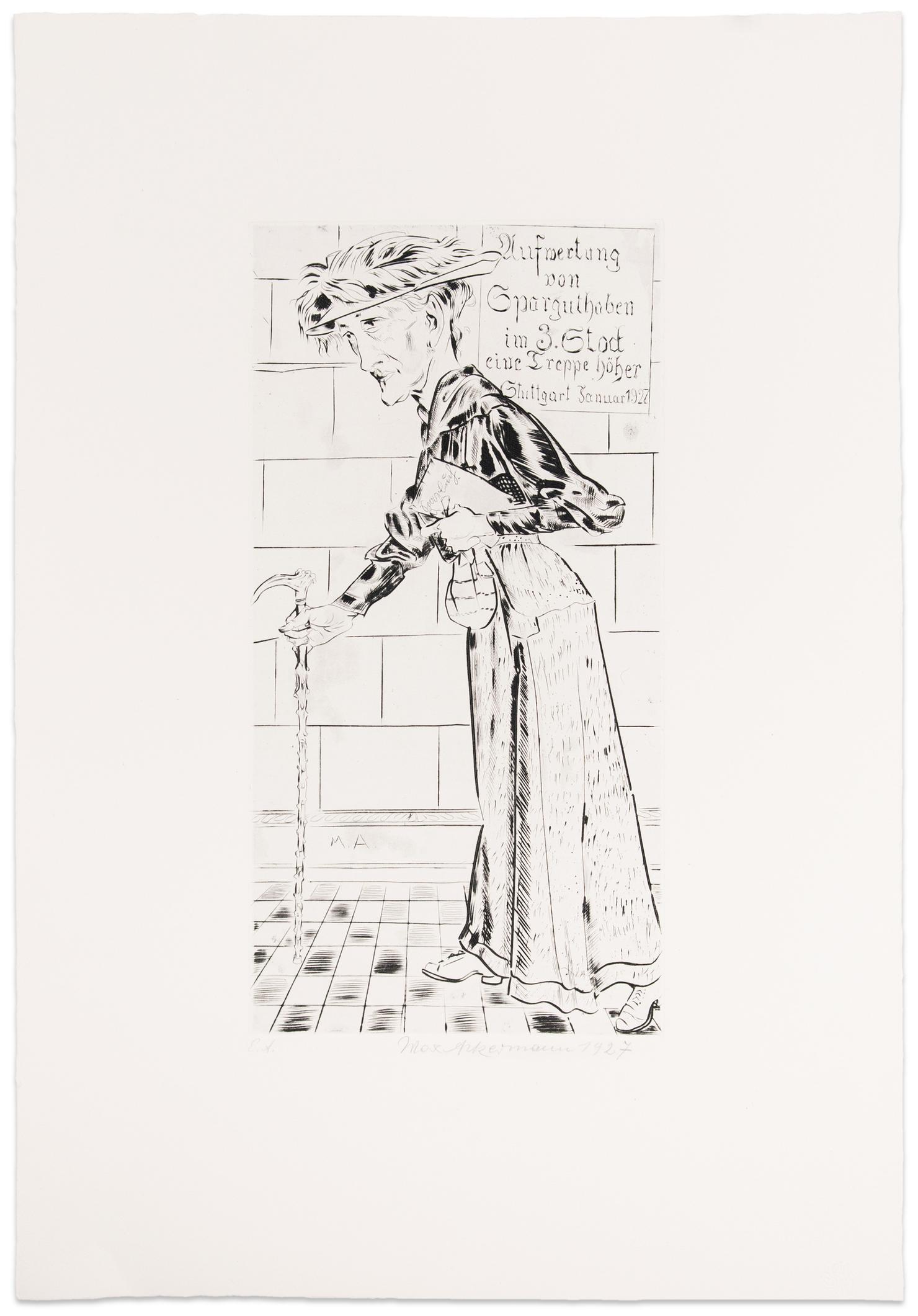

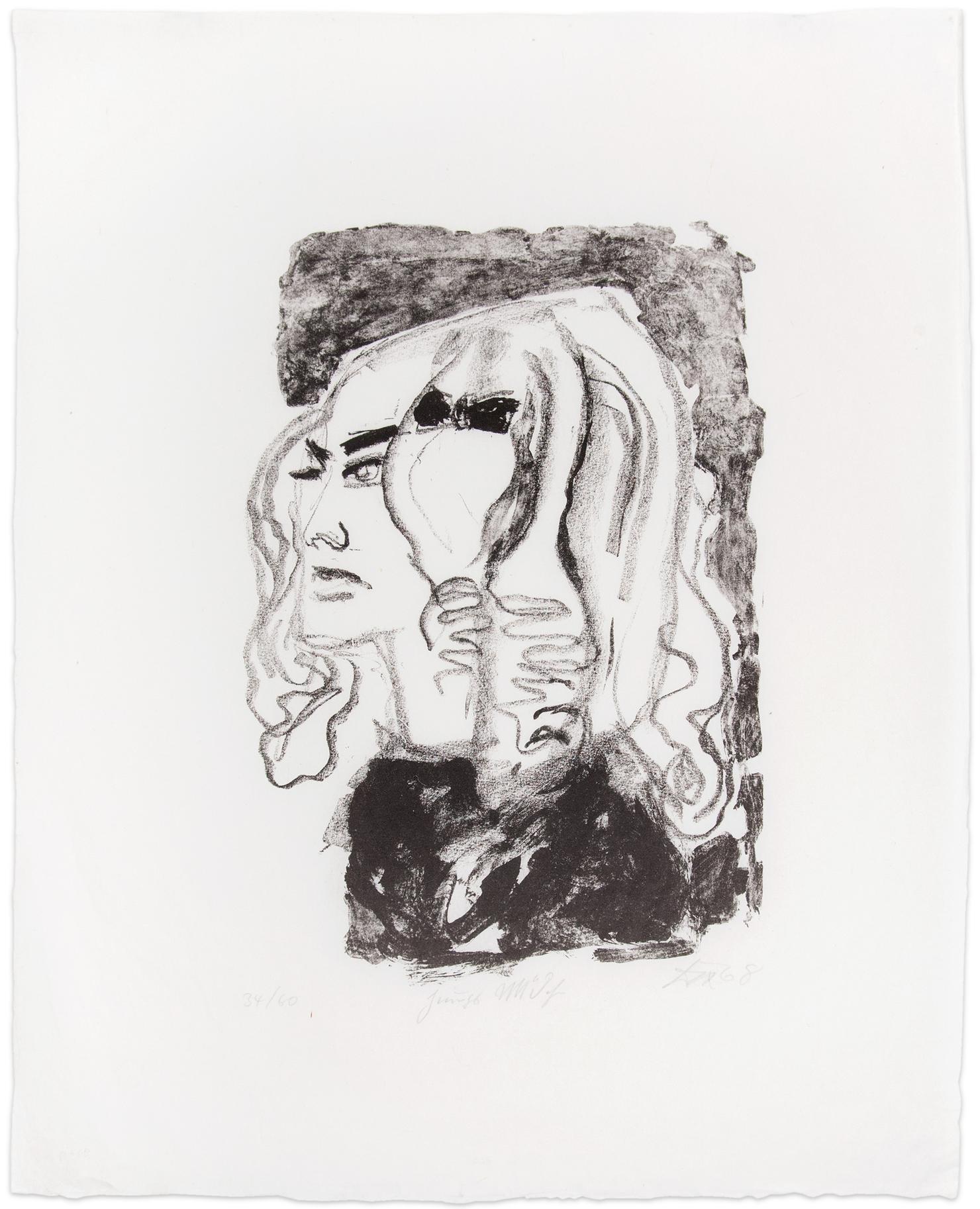

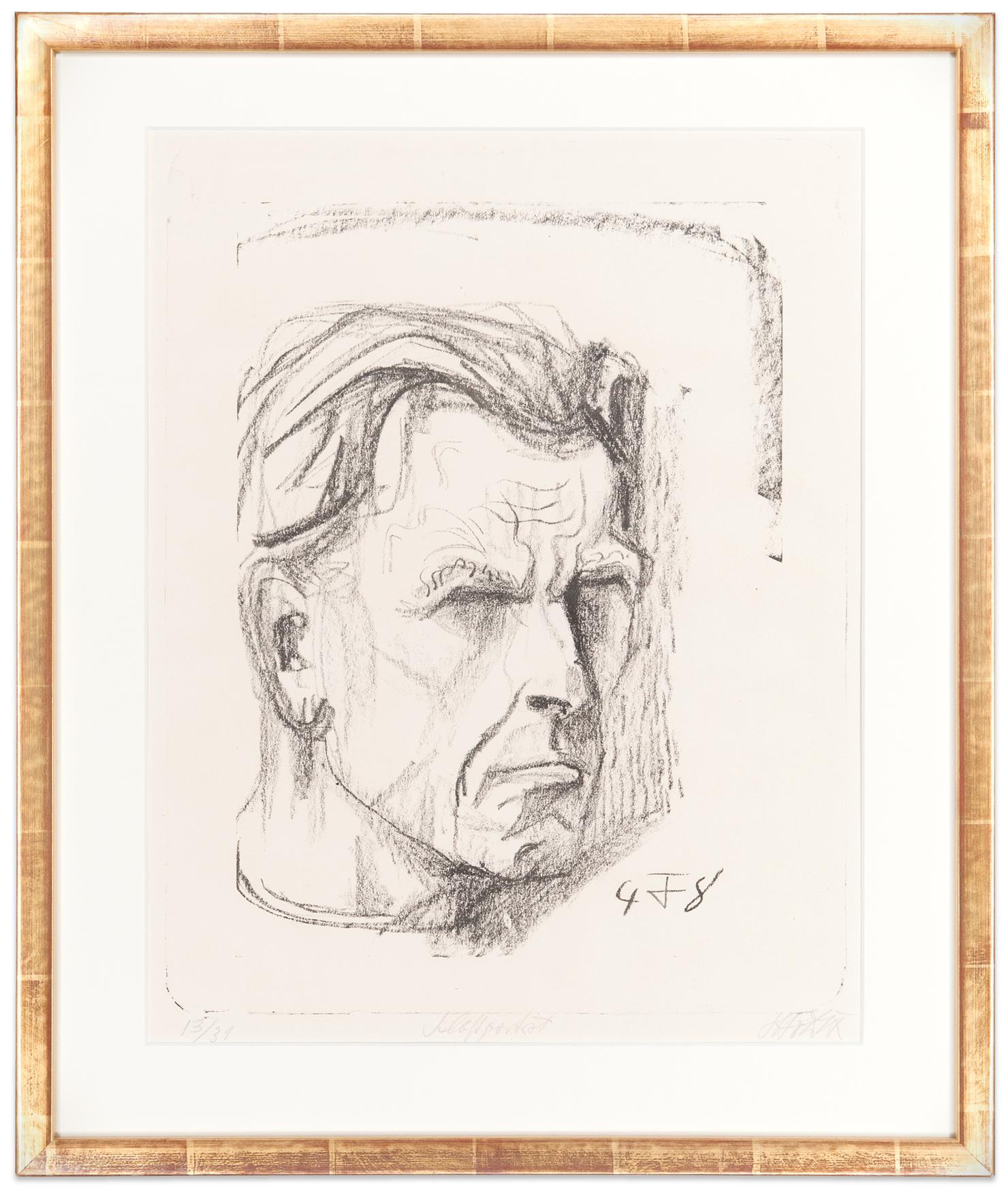

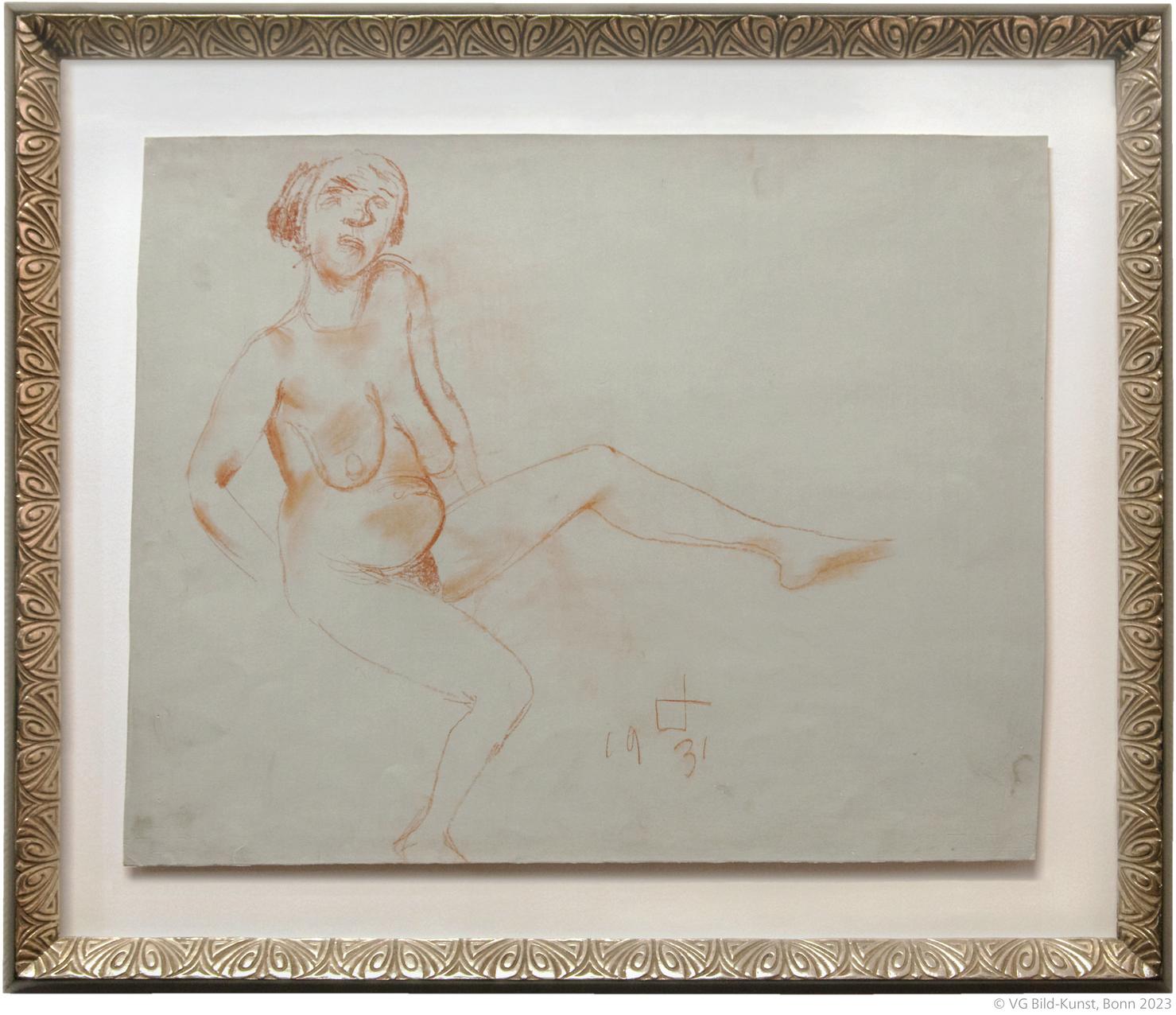

Otto Dix: “Seated Woman”, 1931

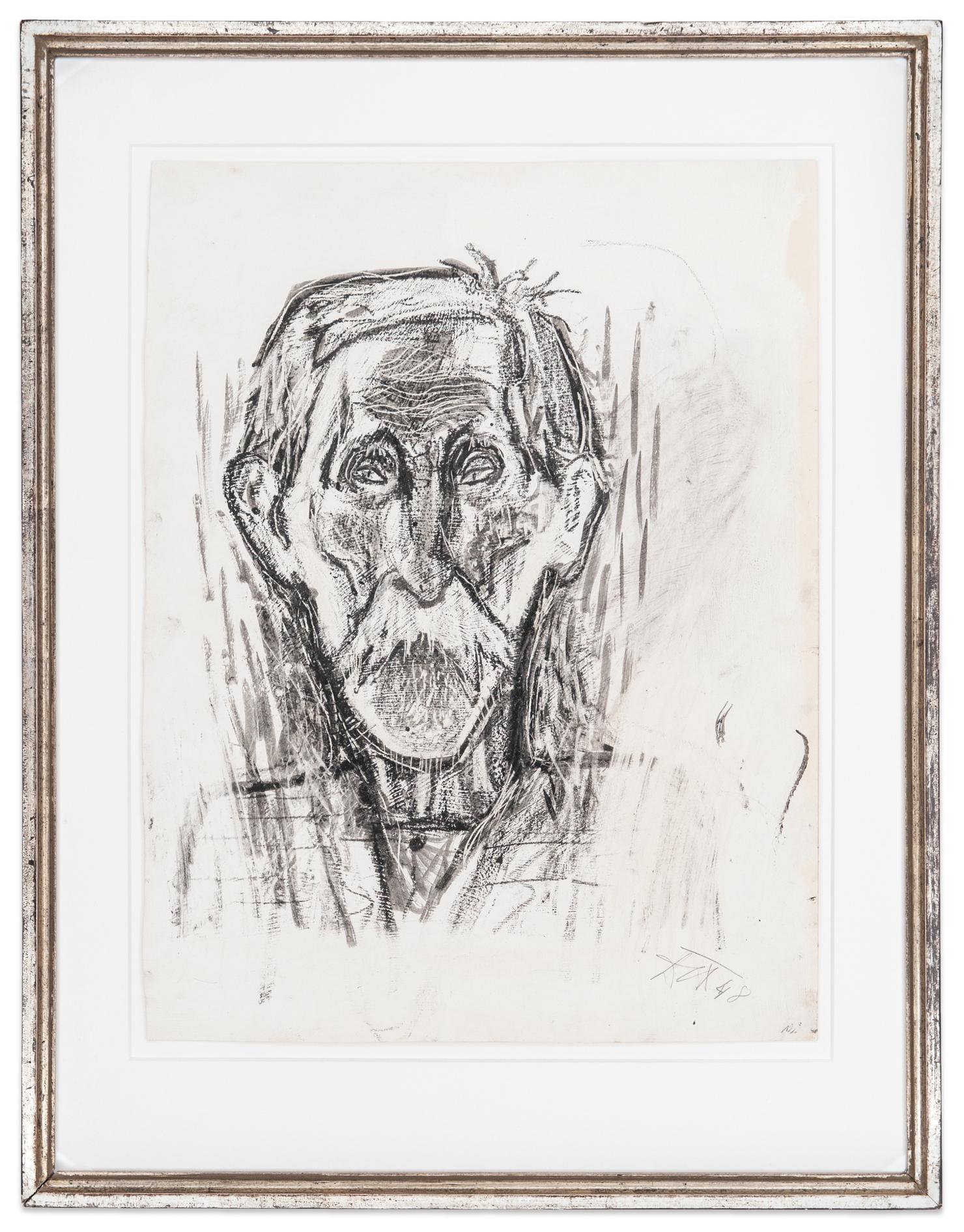

The drawing “Seated Woman”, created in 1931, is a striking example of Otto Dix’s turn toward an Old Master-inspired style of draftsmanship, which characterizes his work between 1928 and 1933. During this period, Dix gradually distanced himself from the precise, sharply contoured aesthetics of New Objectivity and sought out more expressive forms rooted in classical drawing traditions.

The depiction of a seated female figure not only recalls the traditional motif of the nude in art history but also conveys a psychological depth and a meditative stillness. Dix’s use of red chalk—a warm, reddish-brown medium—underscores this reference to historical technique. Used since the Renaissance for figure studies, red chalk enables subtle modeling and a soft, lifelike plasticity that is clearly evident in this drawing.

In “Seated Woman”, Dix largely abandons sharp contour lines in favor of finely nuanced tonal transitions. The surfaces breathe; the modeling is achieved through soft gradients, smudging, and flexible hatching. The figure appears introspective, restrained, and yet intensely present. This ambiguity resonates with the theme of melancholic inwardness that runs through many of Dix’s works from this period.

From an art historical perspective, the drawing represents a conscious return to “Old Master” values, reminiscent of the German Renaissance artists such as Dürer or Hans Baldung Grien. Yet Dix does not simply quote these traditions—he integrates them as part of a deliberate strategy of slowing down and intensifying his artistic focus. In the politically and artistically turbulent final years of the Weimar Republic, and in the face of the rise of National Socialism, this turn toward reduced, contemplative drawing may be seen as a reflection on humanity, vulnerability, and quietude.

“Seated Woman” thus stands as a representative work in Otto Dix’s artistic reorientation: a move away from the sharp, often provocative realism of the 1920s, toward a technically refined, introspective, and atmospherically rich approach to drawing.

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023